| Updated:

Work and plays: Meet Richard Bean, Britain’s most successful contemporary playwright

When Richard Bean’s One Man, Two Guvnors embarked on its first UK tour, every morning the dramatist would email James Corden (the lead) with tweaks and extra lines tailored to whatever audience he was facing that evening. Oh, you’re in Birmingham, swap line X with line Y. Leeds? Make sure you say Z. This tells you two things about his sensibility as a playwright: first, his fastidiousness when it comes to gag-writing; second, his commitment to Britain in its entirety. The weighty concrete of the National Theatre may be his natural habitat these days, but Bean is no metropolitan flaneur. Born in Hull in 1956 to a policeman and a hairdresser, he worked in a bread factory and as a recruiter before turning to stand-up aged 35. “You need two things for stand-up comedy,” says Bean. “Funny bones, and steel.”

He could do the jokes, but lacked the requisite thickness of skin, and after six years turned to theatre, a medium he says strikes the “perfect balance between comedy and ideas.” Since his first play – 1999’s Toast – his career has been a blur of glowing reviews, West End transfers and box office kerchings. In 16 years he’s written 20 plays (more than most writers manage in a lifetime), almost all of them hits. One Man, Two Guvnors – a smash on both sides of the Atlantic – is one of the most successful plays of modern times. Last year his lacerating phonehacking satire Great Britain delighted critics and audiences, debuting at the National and transferring to the West End. In 2014 he also wrote the book for Made in Dagenham, had a historical drama, Pitcairn, performed at the Globe and an acclaimed version of Moliere’s The Hypochondriac put on in Bath.

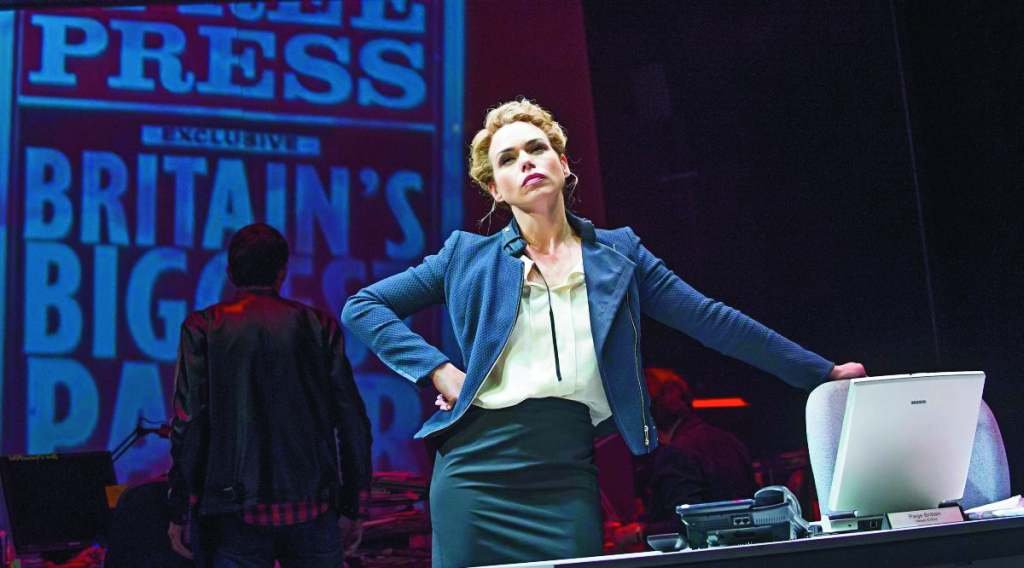

Billie Piper in Great Britain

Up next: a West End revival of his 2002 play The Mentalists starring Stephen Merchant and Steffan Rhodri. The production stars Merchant as Ted, a rambling fantasist intent on reshaping the world from a Finsbury Park hotel room with the help of best friend and amateur cameraman Morrie (Rhodri).

“Ted and Morrie were thrown together as young boys and they ended up being best friends despite being completely different,” says Bean. “One is liberal left wing, the other is authoritarian right wing, so there’s sort of an odd couple thing going on.”

Which character does Bean identify with more? “In the 14 years since writing the play I’ve realised Morrie and Ted are two sides of my own personality. Sometimes I’m a bit like Ted. If there’s a cyclist on the pavement I’ll shout PAVEMENT’S FOR PEDESTRIANS like a nutter. But then I’ll sit down with a friend and talk to them about their problems and I’m permissive and liberal like Morrie.”

James Corden in One Man, Two Guvnors

Bean is known for big, “state of the nation” plays. What did the recent election tell us about contemporary Britain? “All these experts telling us there’s going to be a hung parliament, they were all wrong. Maybe that’s the lesson: don’t listen to experts. It’s like global warming, everyone saying we’re going to drown in 15 years. Do you remember acid rain? I remember reading an article years ago which said there wouldn’t be a single tree left in Scandinavia, and the truth is, you can’t move for f***ing trees.”

Bean enjoys slaying sacred cows. The Heretic (2011) questioned orthodoxies on climate change, and his 2009 play, England People Very Nice, was met with cries of racism from the Guardian. His portrayal of a buffoonish Asian police chief in Great Britain also left a sour taste in the mouth for some. Does it irritate him when liberals raise moral objections to his work, or is it proof he’s doing it right? “I’m chuffed if the Guardian slags off my work. I’m not talking about their critic Michael Billington, he treats me no differently to anyone else. But with England People Very Nice they sent staffers to slag it off just because they heard it was racist. In fact, the play was about four waves of immigration and the conceit was that new asylum seekers were playing all the characters. I think it’s one of my best plays – partly because the Guardian hated it. The idea that the Guardian is squeaky clean is ridiculous. Everyone knows it was born out of a tax dodge so I can’t resist having a little dig.”

What newspaper does he read? “The Guardian.”

Stephen Merchant rehearsing for The Mentalists

Bean likes to keep up with all sides of political debate. “On my Kindle, where I read my papers, I’ve got the Guardian and the Times. I also read the New Statesman and the Spectator. I enjoy the Spectator much more: the New Statesman is sanctimonious twaddle, but you’ve got to read it. You’ve got to get Morrie’s view and Ted’s view.”

Does the real life he led before becoming a writer-performer mean he’s better-equipped to analyse British society? “The year I spent working in a factory was the best for becoming a writer because I was doing six 12 hour shifts a week standing listening to dialogue. When you do boring factory work, if you’ve got the opportunity to talk you’re talking to entertain each other. You go deeper and deeper and get more and more intimate. For me that year spent working in the bakery was the best year of my life in terms of becoming a playwright.”

Merchant and Steffan Rhodri on the poster for The Mentalists

It was his factory experience and his involvement with the bread strike of 1978 that convinced the producers of Made In Dagenham to entrust him with the book for last year’s musical starring Gemma Arterton. Despite decent reviews and a commanding central performance, it closed in April, giving Bean a rare taste of failure.

“We were disappointed when it closed because everyone who saw it seemed to have a really good time. It was a big theatre and those ticket prices are very expensive. Gemma was especially disappointed. She felt she’d done a brilliant job and she had. She’s a fabulous actor and she can sing. But we got some very strange and unkind reviews from certain quarters. Theatre reviews – that’s the sea that we fish live in.”

Still, it must be satisfying reading good reviews? “The most satisfying thing for me is sitting in my shed and writing something that makes me laugh or cry. That’s what I find really satisfying. A room full of people laughing or a room full of people enthralled is an extraordinary thing but to make myself laugh, with my cup of tea, that’s what makes me happy.”

Merchant stars alongside Rhodri in The Mentalists at the Wyndhams Theatre from 3 July to 26 September thementaliststheplay.com