Why you should never, ever bet against UK house prices

Remember the start of the year?

“UK house prices have gone into sharp reverse over recent months. And we expect that elevated mortgage rates will result in at least a 12 per cent price correction,” so said Capital Economics at the time.

This is from building society Nationwide last week: “While annual house price growth remained negative in April at minus 2.7 per cent, there were tentative signs of a recovery with prices rising by 0.5 per cent during the month.”

April’s rise comes after seven straight months of relatively small declines. Not the cataclysmic collapse that was predicted – well, not just yet.

In fact, other house price trackers suggest prices have barely dropped.

Rightmove’s index has slipped into negative territory in just three out of the last 12 months. Halifax says prices were more than one per cent higher in March compared to the same period in 2022.

To their credit, it’s easy to see why experts were warning of a similar house price correction to that which Britain experienced in the early 1990s.

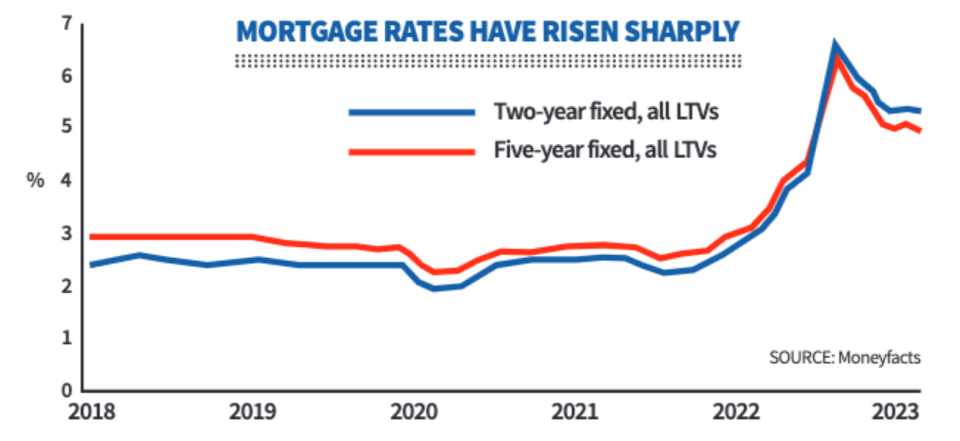

Mortgage rates had still yet to fully abseil from their stratospheric highs reached after Liz Truss’s haphazard £45bn tax-cutting mini budget.

The rate on a typical two-year mortgage jumped to 5.79 per cent from 2.38 per cent over the year to January 2023, according to data provider Moneyfacts. A similar rise was recorded for five-year mortgages.

House prices had cumulatively advanced at least ten per cent since the pandemic – which fashioned a unique surge in demand for large properties with gardens and outside cities.

Under those conditions, lots and lots of buyers were predicted to couch their home ownership dreams for another day.

There’s two key metrics of affordability in the housing market: how much the average price is as a multiple of average earnings and what share of typical households’ monthly budgets are spent on mortgage payments.

Both have been severely stretched. A price correction looked then a very reasonable wager.

The housing market is also highly sensitive to joblessness projections which, headed into 2023, the Bank of England reckoned would be near five per cent by the end of the year, a chunky increase.

There was also real concern – and still is – about families absorbing the sharpest hit to their living standards on record, crimping their capacity to push ahead with home purchases.

In sum it was all fairly bleak. But just as the UK economy has defied gloomy predictions – the Bank thought we were headed for a drawn out recession, a call it has ditched – so has the housing market.

“Demand is likely to continue to recover as mortgage interest rates fall, with some buyers currently holding off in the hope of securing a more attractive mortgage deal later on in the year,” estate agent Savills said in its latest market update.

Joblessness has also held at multi-decade low levels – albeit flattered by an exodus of older Brits from the workforce – which should strengthen banks’ confidence to extend home loans. Consumer confidence is on a decent run.

So all in on rising house prices? The fundamentals suggest there are still reasons to suspect house prices will eventually end up a lot lower by the end of the year. As Andrew Wishart of Capital Economics points out, “the decline in mortgage rates from their spike after the ‘mini’ budget is now over”.

Bank Governor Andrew Bailey and co are tipped to raise interest rates for the 12th time in a row on Thursday, probably by 25 basis points to 4.5 per cent.

The difference between what lenders pay to secure funding for mortgages and what they charge on those products has crimped substantially, meaning they could start raising rates to widen margins.

First time buyers still have little incentive to enter the market. Help to Buy is over (though Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is reportedly mulling bringing it back with a fresh lick of paint) and home purchases are still more expensive than renting, leaving a pool of demand untapped.

Penny-pinching Brits might be more motivated to replenish savings they’ve used amid the cost of living crisis rather than stump up the cash for property.

And there’s a risk lenders retreat from the credit market if there’s more US banking failures after Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic.

Right now, the trajectory of house prices is anybody’s guess. Bleak recession forecasts have been canned because the economy has performed much, much better than everyone anticipated.

Could the same happen to house prices?

Homeowners will certainly be hoping so, even if those looking to buy for the first time might wish otherwise.

WHAT I’M READING

The economy’s better-than-feared start to the year is beefing up households’ confidence in their personal finances. According to investment bank Deutsche Bank’s household survey, which comes out every couple months or so, families are much more optimistic about their income levels in the coming months. That’s feeding their savings appetite, with the survey revealing saving intentions jumping four points. Poorer and middle income households were the most likely to expect to step up savings, which is odd given they’ve been the hardest hit by soaring living costs. Richer households’ intentions were down slightly, probably because they’ve already bagged gains from higher interest rates.

YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED

Brits pulled a record £4.8bn from banks after SVB and Credit Suisse failures, figures from the Bank of England last week unveiled. That’s a lot of cash. Part of that would’ve been driven by concerns about the health of the UK banking system. Lots of money piled into the government-guaranteed National Savings and Investments scheme, which offers a full back stop on all capital compared to lenders’ £85,000 insurance. Others would’ve piled into gilts to benefit from comparatively higher returns. Speculation has gathered pace about the Bank of England forcing lenders to hold back more cash to withstand future bank runs. That would weaken incentives for customers to yank money out from their accounts.