Why Suez Canal disruption may not have a huge impact on inflation

Security fears in the Red Sea have sparked widespread concern over the storm to come for the global economy.

Since mid-November, Iran-backed Houthi Rebels from Yemen have been launching attacks on ships using the Suez Canal, one of the world’s busiest trade routes.

Shipping costs have increased in response to the violence as major container lines, including Maersk and MSC, are forced to send traffic around South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, a diversion which can add nearly two weeks to voyage times.

Suez Canal crossings represent 12 per cent of global trade flows, according to Lloyd’s List. More than a quarter of the vessels are container ships, which carry most of the world’s manufactured goods and products, while tankers and bulkers also make up a significant portion of traffic.

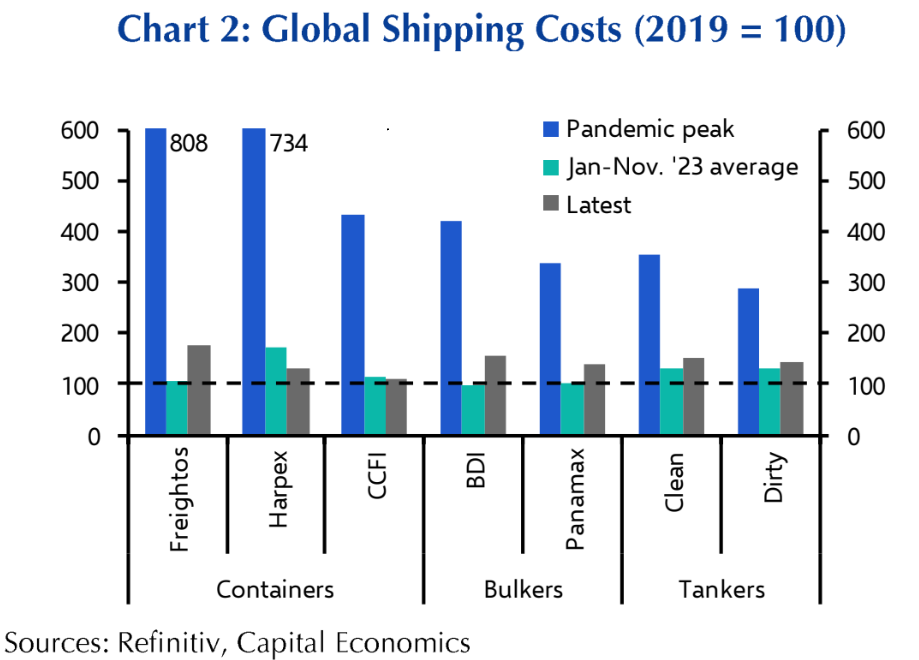

The Shanghai Containerised Freight Index (SCFI), the most widely used measure of freight cost, has risen 88 per cent from early December to the highest level outside of those seen during COVID-19 when rates went haywire in the post-pandemic shipping boom.

Maersk’s chief executive Vincent Clerc warned last week it could take months to reopen the Red Sea route.

High street retailers, major supermarkets and gloomy forecasts have dominated media headlines, warning the supply chain chaos will bump up prices for consumers at checkout and could leave shop shelves empty. There are also fears of a spike in global oil and energy prices in response.

But despite the long-term increase in shipping costs, shipping analysts and economists are sceptical they will feed through into a dramatic resurgence in inflation.

Simon Heaney, senior manager at Drewry, told City A.M. that in a worst-case scenario, where Suez has to be avoided for the entirety of 2024, global container ship capacity would reduce by some nine per cent.

Given the huge crop of ship orders placed during the post-2020 pandemic-era boom, many of which are just entering the fleet, Heaney argued the market would still be “heavily oversupplied”.

“While the situation will impact some trades more than others, on a global level it won’t completely flip the supply and demand story,” thereby limiting the impact on costs down the supply chain.

“There is considerable debate among economists about just how much direct influence higher shipping costs had on inflation during the pandemic and we do not expect freight rates to get near to those levels again,” Heaney added.

Much of the economic concerns centre around spot freight rate increases, but economists told City A.M. these do not paint a wholly accurate picture of the impact on inflation and global markets.

The bulk of shipping costs are contractual rates, agreed over terms of a year or more. These are much less volatile than the spot rate – which measures the cost of getting a container onto the next available voyage.

Analysts at Capital Economics suggested that the impact of higher freight rates on inflation back in 2021 was “just a few tenths of a percentage point” even though ‘spot’ rates surged by 900 per cent.

“While the 50-100 per cent increases in spot freight rates that have been announced this week sound big, they are still a long way off the sort of increases needed to move the needle at the macroeconomic level,” they said.

The other key difference to 2021 is the much weaker demand picture.

In 2021, the global economy was just emerging from the pandemic. Consumers were flush with cash and eager to spend. Now, however, after a surge in inflation and 18 months of interest rate hikes, consumer confidence is significantly lower.

Global supply chains are also much more secure than they were post-pandemic. Having experienced the disruption which followed COVID, firms bulked up their stockpiles and reconsidered ‘just-in-time’ supply networks.

This also gives the global economy significant extra capacity compared to a few years ago. As analysts at Capital Economics noted: “Manufacturers are reporting that it has hardly ever been easier to get hold of key parts and commodities.”

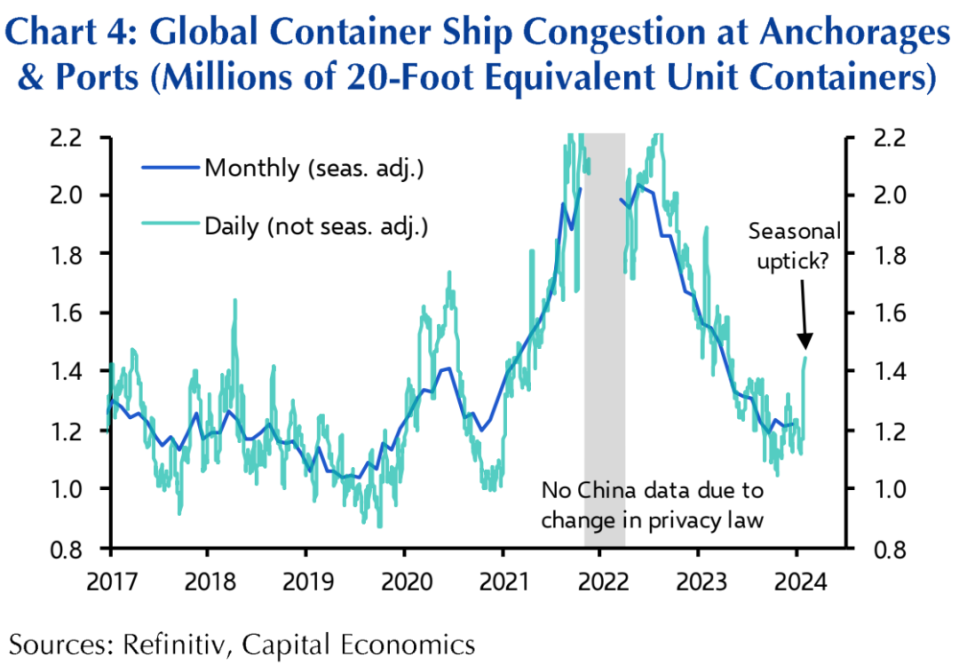

They added that it was not yet clear whether congestion at ports, a key factor in shipping costs and delivery times, was down to seasonal fluctuations, or the Red Sea disruption.

So what could prompt a resurgence in inflation? The real risk is if there is a major escalation in the Middle East, which would end up disrupting energy supplies.

If Iran enters the conflict then the potential disruption to supply chains would be huge. RBC estimates that the equivalent of 10 per cent of OPEC oil production passed through the Red Sea while 40 per cent passes through the Strait of Hormuz.

Reflecting these concerns, oil prices briefly spiked at the turn of the year when Iran rejected calls to end support for Houthi attacks. However, analysts think that the prospect of Iranian interference in global supply chains is relatively low.

“Iran and its Houthi proxies lack the ability to project naval power, and are completely outmatched by the US-led coalition providing safe passage to Red Sea shipping,” Robert Ryan, chief commodity and energy strategist at BCA Research, said.

“Iran and its Houthi proxies lack the ability to project naval power, and are completely outmatched by the US-led coalition providing safe passage to Red Sea shipping.”

Robert Ryan, chief commodity and energy strategist at BCA Research

Without further escalation, oil prices are unlikely to rise significantly. Despite weeks of disruption in the Red Sea, oil prices have mostly remained below $80 a barrel.

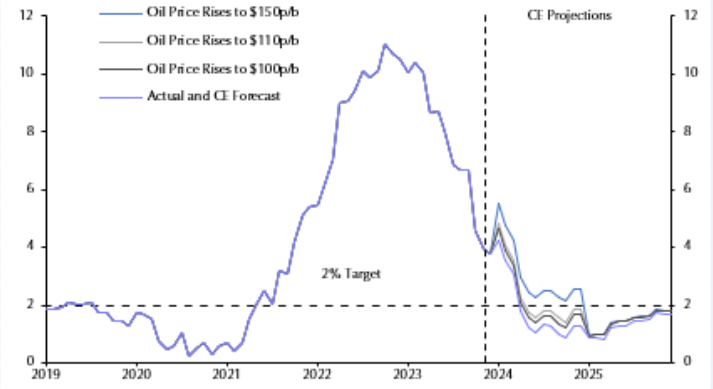

Ashley Webb, a UK economist at Capital Economics, thinks oil prices will remain around $75 per barrel this year.

Even if oil prices rose above $100 per barrel, Webb argued inflation in the UK would still fall below 2 per cent in May and be 1.8 per cent in December 2024.

“The point is that $10 to 20pb increases in the oil price do not dramatically change the picture,” he said.