Why spurious financial precision may be killing our markets – and our fish

The way we handle uncertainty determines our future. Many of mankind’s self-created problems, from financial crises to environmental devastation, arise from poor analysis of future risks and rewards. We lack confidence in our tools for handling uncertainty. Within the financial sector we’ve been partially burned by derivatives, mark-to-market, or value-at-risk. Scotland’s independence referendum may represent the latest reassessment of future scenarios, but there will be many more. We need to improve our toolkits. We need to improve our data.

“Wicked problems” is a phrase popularised in the 1970s to describe messy, circular, and aggressive problems. According to Laurence J Peter of The Peter Principle fame, “some problems are so complex that you have to be highly intelligent and well informed just to be undecided about them.” In our book, The Price of Fish: A New Approach To Wicked Economics And Better Decisions, Ian Harris and I explore how we can meld four “streams” in any complex scenario – choice, economics, systems and evolution – to make better decisions about wicked problems. We also make suggestions. One such proposal is Confidence Accounting.

Confidence Accounting encourages companies and audit firms to use ranges, rather than discrete numbers, for major accounting entries. In a world of Confidence Accounting, the results of audits would be presentations of distributions for major entries in financial statements. Ranges provide a fairer representation of results and valuations, reduce the number of footnotes, and aid measuring audit quality over time.

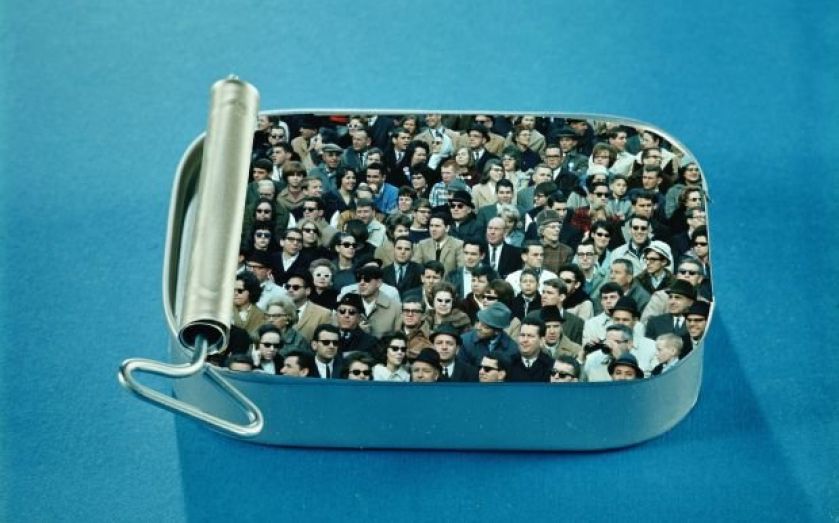

One way to understand the importance of Confidence Accounting is to talk about fish. Back in the early 1900s, on rumours that sardines had disappeared from their traditional waters in Monterey, California, traders started to bid up the price of tinned sardines; a vibrant market ensued and the price of a tin of sardines soared. A classic bubble. One day, after some successful trades, a buyer chose to treat himself to an expensive snack; he opened a tin and ate the sardines. They tasted awful, so the buyer called the seller and told him the sardines were no good. The seller said, “you don’t understand. Those are not eating sardines, they are trading sardines.” Ultimately, sardines off California were fished out by the 1950s. Had markets worked well on their own, and had people really known the price of fish over space and time, we wouldn’t have overfished the North Sea, the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, or Monterey.

Virtually all accounting entries require judgement, meaning that a range of values might apply. Accounting practices exclude the truth behind overly-precise specific values. Over-precision forces companies to value assets, such as fish or fossil fuels, at higher or lower values than they might think they are worth in the longer term, to the detriment of other natural resources or fossil fuels. A good example has been the stranded fossil fuel assets argument: if perhaps four-fifths of the fossil fuels on balance sheets are unburnable in the long term (like those fish were inedible), why are they calculated at full current prices? Using specific values when ranges are needed exacerbates volatility in markets and fish stocks.

There are numerous “judgement calls” in financial statements – revenue recognition, tax liabilities, goodwill and intangibles, asset valuations, share-based payments, and management and performance fees. Confidence Accounting would have these judgement calls represented as ranges. There are complicated ways of expressing ranges, such as candlestick diagrams common among traders, time-based fan charts for economists, and box and whisper diagrams for scientists. There are simple ways. Simply state the bottom value, the expected value, and the top value, with a judgement on the likelihood that the value is in that range.

Confidence Accounting may be started as easily as having audit committees ask their auditors to discuss the accounts using ranges. A simple approach to ranges can go a long way in helping to incorporate knowledge and experience in discussions between audit committees and their auditors. Andy Haldane of the Bank of England has remarked that his “hope is that this proposal moves our thinking a step closer towards a set of accounting standards for major entities that put systemic stability centre stage. In the light of the crisis, anything less than a radical rethink would be negligent.”

Much of the tension for accountants has been generated by single historic cost numbers colliding with the need for judgement about the future. More tension has been generated when historic and current accounts collide with future-looking risk scenarios. Much of the tension is released when ranges are recognised as fundamental to any discussion about financial reporting. Perhaps when we relax a little about precision, we can gain confidence about our decisions on markets and fish.

Michael Mainelli is emeritus professor of commerce at Gresham College, executive chairman of Z/Yen Group, and principal adviser to Long Finance. His latest book is The Price of Fish: A New Approach to Wicked Economics and Better Decisions, co-written with Ian Harris (Nicholas Brealey Publishing, £12.99).