Why politicians will always struggle to sell action against climate change to the public

The two week long Paris conference on climate change seems to be dragging on interminably. There are obviously many reasons why such summits find it difficult to reach meaningful agreements. But a fundamental one is that the electorates of the West are being asked to bear substantial costs right here and now, in return for a stream of benefits which will only become apparent well into the future. Closer to home, we see similar issues with major infrastructure projects such as the new airport runway in London and the high speed rail project HS2. We pay for them upfront, and the gains appear later.

Economists have a way of analysing this problem. They even, as usual, have their own special phrase to describe it, “social time preference”.

The Treasury publishes the Green Book, which describes the methodology to be employed in the appraisal and evaluation of the use of public funds in investment projects. A substantial part of it is devoted to how to compare the value of the costs incurred now and of the benefits received in the future. If you are offered the choice between being given £100 today or £100 next year (inflation adjusted), you will naturally prefer to have the money in your hand immediately. But how much more would you need to be offered to persuade you to wait?

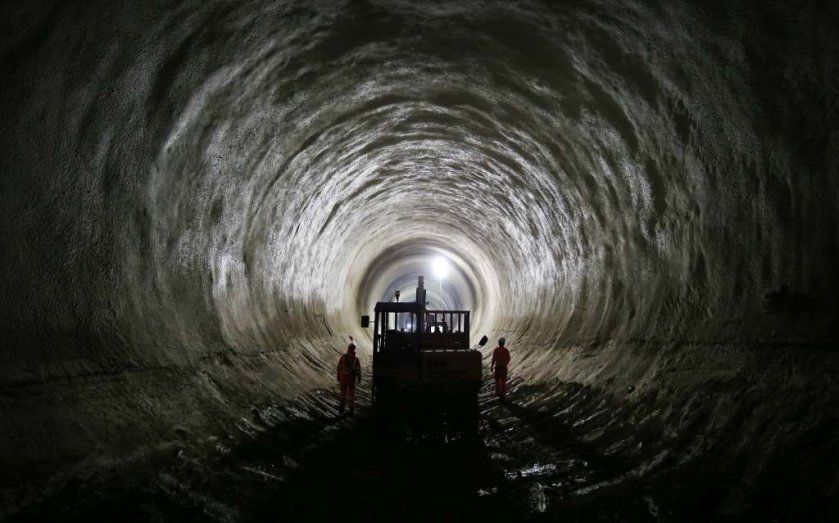

The Treasury calculates, citing some impressive academic work, that the rate to be used on public projects is 3.5 per cent a year. So if an investment yields a benefit of £103.50 next year, this is essentially the equivalent of receiving £100 today. The impact cumulates strongly, so that a benefit of £100 in 20 years’ time is only the same as £50 today. The numbers for Crossrail, for example, were ground through the same process, and came out positive. The scheme was calculated to be worth building despite the high initial costs involved in money and disruption.

In the case of climate change, the predicted benefits of taking action now stretch hundreds of years into the future. But the impact of the social time preference rate is ruthless. Very long-term benefits become worth more or less nothing when translated into today’s value. Yet people in the West are being asked to bear the costs now.

This was the problem faced by Lord Stern in his famous review written for Gordon Brown in 2006, the Economics of Climate Change. His advocacy of spending 1 per cent of the world’s GDP immediately to combat climate change has been very influential. But to get the numbers to stack up, he had to set the rate of social time preference close to zero.

Martin Weitzman of Harvard wrote an important paper nearly 20 years ago arguing that the discount rate should be reduced for the “far distant” future. The Treasury does acknowledge this, and its 3.5 per cent rate only applies for the next 30 years. Even so the basic dilemma remains. Pay now, and your grandchildren might benefit. No wonder democratic politicians struggle to sell the idea.