Why have the Bank of England and the IMF been so wrong on the UK economy?

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Bank of England have been so wide of the mark on the UK economy of late that it’s reasonable to conclude economic forecasting is pointless.

The simple message the pair have conveyed is that they underestimate the UK economy time and time again.

Their respective upgrades leave the country in a much better position. IMF economists think Britain’s on course for a 0.4 per cent economic expansion this year, better than Germany who, after revisions to GDP estimates, is now in a technical recession.

Bank experts are a bit less optimistic, projecting 0.25 per cent growth this year.

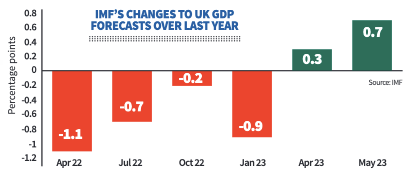

Since January, the IMF has lifted its UK growth prediction by one percentage point (see graph), up from an expected 0.6 per cent contraction at the turn of the year.

Monetary policy committee officials’ record is worse. The Bank last November projected the longest recession in a century, taking 1.5 per cent off of GDP this year, a 1.75 percentage point upward swing based on its freshest report.

It’s easy to point the finger at these economic behemoths and blame them for being so wrong. And you’d be fair to do so.

But forecasts are designed to illustrate what the direction of travel is, not the exact destination. It’s better to be broadly right than precisely wrong.

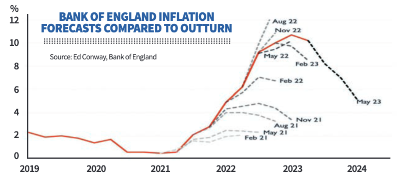

Part of the reason why the Bank has struggled to get a handle of inflation is because its forecasting methods are geared toward a past environment of economic stability.

Britain was in big trouble when these forecasts were made

Assumptions that underpin models have been upended by the series of global economic shocks, as admitted by Bank chief economist Huw Pill last week.

“We are trying to understand why we have made those errors, interpret those errors in terms of the behaviour, and make an assessment in terms of how it will continue,” he said at a grilling by the treasury select committee.

In November, when those bleak forecasts were cast, Britain really was in big, big trouble. Gas – which we consume a lot of – prices were crazily high and weren’t really exhibiting any signs of falling.

Families were staring down the barrel of losing nearly six per cent of their real income, amounting to the largest living standards shock on record.

Spending was expected by the Bank and IMF to slide in response, driving the bulk of the economic downturn.

Escaping such a real income shock caused by the price of imports soaring isn’t really possible, although governments can alleviate the pain on the poorest, which Jeremy Hunt and Rishi Sunak partly did by freezing energy bills at £2,500.

That move also partly convinced the Bank to ditch any trace of its recession call earlier this month.

Those spikes in gas prices unfolded very quickly.

Their recent decline back to pre-Russia-Ukraine war levels has lapsed over a similar time frame, rapidly easing pressure on household finances and sparking the recent round of forecast reversals.

In its latest report, the Bank assumes the price per therm of natural gas averages £1.37 this year. Back in November, they thought it would be £3.56, nearly triple.

Another remarkable story amid all this economic turbulence has been the strength of Britain’s jobs market, constantly taking the IMF and Bank by surprise.

That has been driven by more robust spending convincing companies to keep staff. Fears about being unable to source new recruits once existing workers are let go has led to labour “hoarding,” James Smith, an economist at ING told City A.M.

There’s a downside to all this economic overperformance: stronger inflation.

Core inflation last month jumped unexpectedly to 6.8 per cent, smashing all forecasts, signalling price pressures have “become more embedded in the wider economy, which is at least in part thanks to… slightly stronger” demand, Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG UK, told City A.M.

The IMF now thinks inflation won’t return to the official two per cent until the middle of 2025 – six months longer than previously thought.

It’s looking increasingly likely the Bank will have to ratchet up interest rises again to crush inflation.

Economists think there’s a chance Bailey and co will revert to the 50 basis point speed at the next MPC meeting on 22 June. Markets think the eventual rate peak will be 5.5 per cent.

Reaching such a level would put a recession back on the table, one that is perhaps needed to kill off price rises.

The Bank must be alive to the fact that the initial price burst sparked by the external energy price shock is now pushing up inflation across the economy.

Domestic factors are beginning to run the show.

Failing to accurately project how they will play out raises the risk of the Bank losing credibility with the public.

WHAT I’M READING

Yet more pain is on the way for homeowners. Over the next year, about 1.6m fixed rate mortgage holders will see their deals expire, meaning they either have to roll on to a new contract with a much, much higher interest rate or sell up. That’s according to the Resolution Foundation, who estimate since the Bank’s first rate rise around 4m Brits have been subjected to changes to their mortgage bills.

YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED

Germany was in a recession over the winter after all. Europe’s economic powerhouse met the technical definition of two back to back quarters of contraction after the country’s stats office revised down its first quarter GDP estimate to minus 0.3 per cent from zero per cent. That followed a 0.5 per cent drop in the final three months of last year.