Why do economists think public investment is good for growth?

As the Budget approaches it seems clear that the government is preparing to ramp up public investment.

In interviews, Chancellor Rachel Reeves has pledged to “invest, invest, invest“, confirming that she will revise the fiscal rules to “take account of the benefits of investment, not just the costs”.

Although its not exactly clear what the details will be, the direction of travel is clear and has been welcomed by many economists.

So why is public investment so important and how will an increase impact the economy?

What is public investment?

To understand why economists think increasing public investment will be so helpful, its worth breaking down what it is and where it goes.

Very basically, public investment is money that the government spends on creating long-term assets. This can be physical assets as well as intangible assets.

About half of public investment goes towards ‘net capital formation’, which just means tangible assets.

Breaking it down further, only about a third of ‘net capital formation’ is infrastructure, like the road and railway network while the remaining two-thirds goes towards public services.

The other half consists almost entirely of capital grants to and from the private sector.

Interestingly, one of the largest components of this part is student loans. Student loan write-offs are counted as part of public investment in the national accounts, making up around one-fifth of total investment over the past few years.

State of public investment

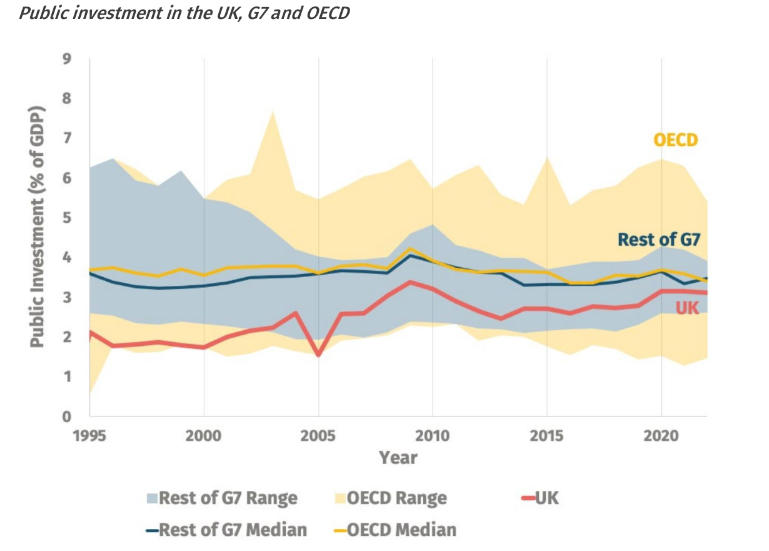

The UK has persistently invested less than other rich economies. According to the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR), public investment as a share of GDP has lagged the G7 average every year since the early 1990s.

In other words, an investment shortfall is not a new problem. However, over that time the impact of persistent under-investment has slowly been building. A small leak in the roof might not have too much of a negative impact at first, but leave it too long and you’ll notice if the roof falls in.

According to the Resolution Foundation, the UK has fewer hospital beds per person than all bar one OECD country. Brits also spend more time commuting than all bar two rich economies, due to under-investment in travel infrastructure.

Choose almost any public service and you will find evidence of under-investment contributing to poor outcomes.

“There are some clear areas where there’s been too little capital spending over the long run,” Karl Williams, research director at the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS).

“There are some clear areas where there’s been too little capital spending over the long run.”

“We’ve seen lots of extra funding for public services without improvements in productivity because it’s often papering over the cracks.”

Over the coming years, the need for investment is only likely to increase as the UK grapples with the energy transition. However, the government has inherited spending plans which would deliver sharp cuts to investment budgets.

Long-term benefits

Most economists think that increasing public investment supports economic activity because it provides solid foundations on which the rest of the economy can grow.

That’s true both for the public services themselves, because public sector workers are equipped with the most up-to-date equipment, and the rest of the economy.

Gregory Thwaites, research director at the Resolution Foundation, said: “Investment into public services is good for the productivity of those services themselves, which makes up around one sixth of economic activity, but it also has knock-on effects for the economy.”

“It means businesses can benefit from healthier, better educated workers. Better transport networks also enable firms to draw on a larger labour market,” he continued.

“It means businesses can benefit from healthier, better educated workers. Better transport networks also enable firms to draw on a larger labour market.”

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the ultimate arbiter of fiscal orthodoxy in the UK, tried to calculate the growth impact of a well-directed programme of public investment.

According to its models, a sustained one per cent increase in public investment could “plausibly increase the level of potential output by just under half a percent after five years and around 2.5 per cent in the long run (50 years).”

Put another way, it would pay for itself over twice over in the long-run. It’s almost like the OBR wanted to send the Chancellor a message.

So what’s gone wrong?

One reason investment is low is that ministers are always tempted to raid capital budgets in order to fund day-to-day spending, particularly when a crisis comes around.

Thwaites said this was a bit like “increasing the number of chefs without increasing the number of cookers”.

Perhaps more importantly, over the past few years the government has effectively had an in-built incentive to cut public investment due to the fiscal rules. The current set of rules require debt to be on a downward trajectory in five years time.

This effectively means that the short-term costs of investment programmes are included in budgetary calculations while the longer-term benefits are not, because it takes longer than five years for the benefits to be felt. Thwaites described the fiscal rule as “crackers”.

Many prominent economists and think tanks have urged the Chancellor to target public sector net worth (PSNW) rather than debt. PSNW is the broadest measure of the government’s fiscal position, including both financial assets held by the government – such as student loans – and physical infrastructure.

Thwaites admitted that there were issues with targeting PSNW. “Measuring this thing is a complete nightmare,” he said, and its also “extremely volatile”.

Nevertheless, Thwaites argued that it was still a better option than cutting back on necessary investments for “accounting reasons”.

What are we waiting for?

There are a few reasons why public investment might not have the kind of impact Reeves would hope.

The first is the UK’s onerous planning regime. Williams argued that this means the UK gets “less bang for its buck” on investment spending, because so much gets spent on consultations and legal battles.

According to Britain Remade, the costs of seeking planning permission for the Lower Thames Crossing now exceeds what it cost the Norwegians to build – yes, build – the world’s longest undersea road tunnel.

There are also some fears about whether the British state is in a position to deliver on these major investment programmes.

Jagjit Chadha, director of the National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR), has long been calling for an increase in public investment. However, this summer, he warned that the UK might not have the “institutional ability” to manage major projects or the “right methods of appraisal” for assessing which projects are most useful.

The OBR has also pointed to the problems of rapidly increasing capital spending. “History also shows that ramping capital spending up quickly is particularly difficult, implying larger underspends than when spending limits evolve relatively smoothly,” it said back in 2020.

The fiscal watchdog’s analysis of 22 investment plans between 1998 and 2007 showed that spending fell short on 19 occasions.

These are not necessarily arguments against the need for public investment, but it is a caveat that it won’t necessarily be easy to secure quick wins.

Williams also argued that the bigger problem for the UK economy was low private sector investment, which he said should be the Chancellor’s main focus.

“The bigger problem is a lack of business investment and so the focus should be on removing barriers to investment, whether that be in the tax system, regulation or the planning regime,” he said.