Why economists might be underestimating the UK economy

The UK economy has made a strong start to the year, fuelled by lower inflation and hopes that the Bank of England will start cutting interest rates in a few months.

Survey data has pointed to a rebound at the start of the year following the shallow recession which finished 2023. The latest round of purchasing managers’ index (PMI) surveys for example show the UK expanding at a faster pace than all major economies, including the much-hyped US economy.

Even so, consensus estimates for 2024 suggest the UK economy will grow only 0.4 per cent, well below the UK’s long-run average.

Not all economists are so gloomy, however. Simon French, head of research at Panmure Gordon, thinks that the UK economy could grow as much as 1.2 per cent. Although this is still below average, it is markedly better than the gloomy consensus.

So what distinguishes French’s optimistic take from the norm?

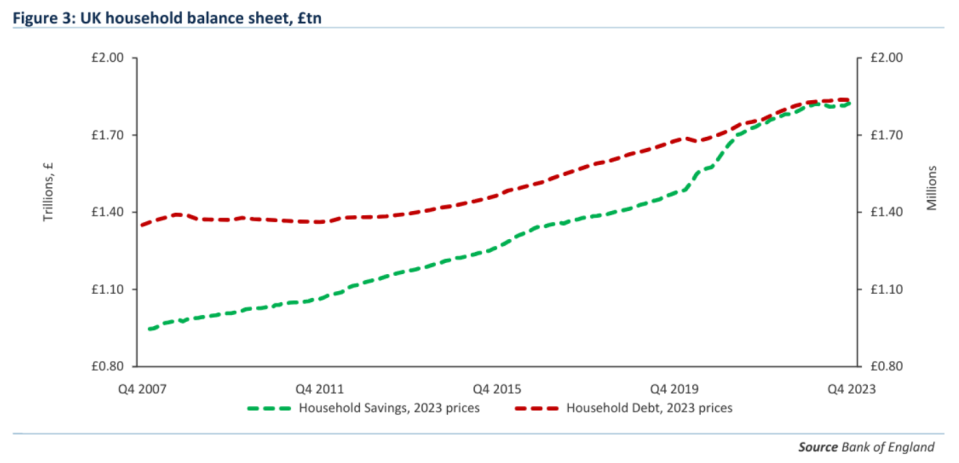

First, French argues that “household balance sheets have never been healthier,” a point which he argues the consensus is underestimating.

Cash and consumer debt now equal around £1.8trn, unlike in much of the previous decade, when debt outweighed savings.

While this partly reflects the surge in savings during the pandemic, household balance sheets have actually steadily been improving since the financial crisis.

“This aggregate picture has, and continues to put a floor under the downside risk to UK consumer spending,” French said.

Prospects for global growth also have improved over the past few months, which should help support the UK’s exporters as overseas demand recovers.

Sterling tends to strengthen when global growth picks up, French noted, which should also ease cost pressures for UK firms importing from abroad.

Finally, households are set to see sizeable real income growth over the coming months as inflationary pressures continue to abate.

The most important disinflationary force comes from energy. Energy prices have fallen rapidly over the past 18 months, a trend which has continued in 2024. Futures are now 86 per cent below their peak in July 2022.

All of this will feed through into household incomes. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) think household disposable income will recover to its pre-pandemic peak by 2025-26, two years earlier than its November forecast.

But it might not all be plain sailing for the UK economy.

One significant factor is whether households choose to spend or save the extra income their extra disposable income. If it is saved, the impact on the economy will be greatly reduced.

Figures out last week showed that the household savings rate increased in the final quarter of last year to 10.2 per cent, well above pre-pandemic norms. French said this was “not particularly encouraging”.

He also pointed to concerns that the labour market, which so far has remained remarkably resilient despite the Bank of England’s interest rate hikes, is “poised to turn”.

Conditions could deteriorate due to a “delayed response to the economic turbulence of recent years and heightened regulated labour cost inflation,” French warned.

He also suggested Labour’s new package on workers’ rights could put up costs further for firms, stymying their capacity to invest in productivity enhancing technology.