Why does the Bank of England (secretly) want to sack you? To hose down the inflation fire

Whisper it very, very softly, but the Bank of England (secretly) is trying to force you out of the job.

That’s right. Governor Andrew Bailey wants to toss you to the wolves in the name of the fight against inflation.

That’s overegging it. No one is directly trying to make someone else unemployed.

A kernel of truth exists though in the Bank and even Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s actions having an indirect impact on people’s lives that will eventually leave them poorer.

Ten straight interest rate hikes generating a cumulative 390 basis point tightening cycle is unusual, the effects of which have yet to properly spread across the UK economy.

Despite the dire recession warnings, the jobs market has held up pretty well.

Unemployment is hovering at multi-decade lows, vacancies have been running around record highs and pay has been rising, in cash terms, at the quickest pace in around 20 years.

Signs that the workforce is ever so slightly fraying are creeping into the key pieces of economic data.

Firms’ appetite for workers has chilled, primarily as a result of not expecting to need more staff amid the economic downturn. Companies have probably made a big dent in clearing huge vacancy backlogs.

“The employment index of the S&P Global composite PMI survey has been consistent over the last three months with broadly flat private-sector employment,” Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at consultancy Pantheon Macroeconomics, said.

Latest Office for National Statistics data on the labour market for January indicate planned redundancies are tracking close to their early 2021 trend when the country was in the teeth of Covid-19 curbs.

Staff availability has climbed to a 23-month high, according to KPMG and the Recruitment and Employment Confederation, mainly because companies are trimming costs by letting workers go.

Real wage growth has been sluggish for more than a decade

What all these changes mean is that resources have been freed up in the UK economy, what economists call, slack.

Slack is an important factor in determining the inflation rate in an economy.

Too few workers and too hot demand for staff can force wages far and above inflation and bake in elevated price increases for years to come.

The opposite happens when demand is low and workers are in surplus. In the jobs market, bargaining power oscillates between these two positions.

For about 18 months, workers have held all the cards, helping to push private sector pay growth up around seven per cent, although regular pay increases have actually trailed inflation for 14 straight months.

Tides are beginning to shift in the UK though. Workers will soon be forced to trim wage expectations and owners of capital forced to ditch assets cheaply. Inflation should come down.

What the Bank is trying to prevent is expectations of future inflation staying high among businesses and workers.

That could spark what economists call second-round effects, a cycle in which workers demand inflation busting pay rises and firms raise prices to offset higher wage bills.

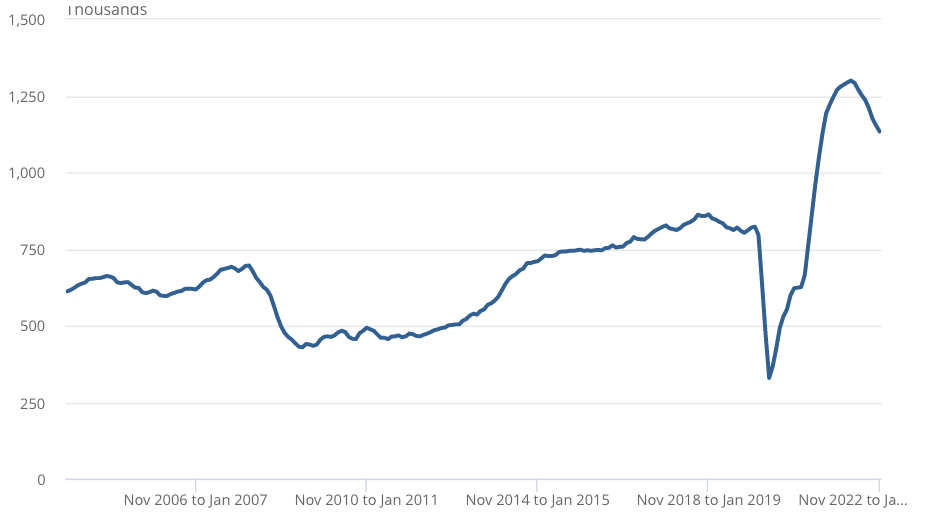

Vacancies are trimming

Keeping a lid on wage growth that isn’t offset by productivity gains is important to taming price pressure, but businesses have also played a role in fuelling the inflation surge by hiking prices to boost profits.

Paul Donovan, chief economist at UBS Wealth Management, highlighted recently that typically “15 per cent of inflation [comes] from margin expansion, but the number today is probably around 50 per cent”.

As usual in economics, nothing is black and white. Many moving parts have contributed to last year’s historic inflation crisis.

And just as several factors have pushed up prices, several factors will bring inflation lower.

We’re now in the early throes of a cycle in which both the Bank’s ten straight hikes and inflation eroding household incomes will begin to soften the economy.

Slack is emerging, but not without a human cost. People will lose their jobs.

While that will bring inflation lower, it’s worth remembering the key source of this 40-year high inflation shock: elevated energy prices caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, not workers trying to shield their living standards.

Energy prices have tumbled, which will bring inflation down, with or without you being sacked.

WHAT I’M READING

I’m sure the economically-minded noted the National Institute of Economic and Social Research’s budget preview last week. It was, as Treasury officials noted, an outlier. Britain’s oldest economic think tank reckon Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has around £100bn to spend on Wednesday, primarily because inflation will stay higher for longer and boost tax revenues. By comparison, the IFS and Resolution Foundation put the fiscal firepower at somewhere around £9bn. BNP Paribas think it could be north of £10bn. Take your pick.

YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED

Couple weeks back, IFS chief Paul Johnson’s book on how much the UK government funds spending was released. Follow the money: How much does Britain cost? couldn’t be more timelier. Grab a copy.