Why Darren Campbell is telling the story of his rise from poverty to Olympic success – and brush with death – before it’s too late

Darren Campbell was in no hurry to write a book until May 2018. A near-death experience has a way of rearranging priorities.

Aged just 44, the British former Olympic champion sprinter needed intensive care after a bleed on the brain caused a series of seizures. The ordeal brought Campbell the stark realisation that he ought to document his remarkable life before it was too late.

“After what happened to me, it hit home that I hadn’t told the story, especially to my children. It felt like I might have missed the opportunity,” he tells City A.M.

Doctors told Campbell that the after-effects of his pituitary apoplexy might include loss of memory or speech.

“When you’re dealing with the brain, it’s a serious thing,” he adds. “I felt I needed to write it because the fear was that I wouldn’t remember a lot of things.”

In ‘Track Record’, which was published last month, Campbell is candid about the terror he felt when the apoplexy struck.

Writing an autobiography required him to revisit those dark days and confront the effect that the ordeal had on his loved ones.

“The process was difficult because it took me back to that moment. Seeing the fear in my family’s eyes really did hit home,” he says.

“I tried to heal as quickly as possible. I wanted to take that fear away from them and give them the belief that everything would be okay.”

Haunted by flashbacks to brain bleed

At first, a man who at his peak ran the 100m in 10 seconds could barely put one foot in front of another.

His recovery was gradual; Campbell estimates it took a year until he felt himself again. And even now, reminders still surface.

“It is something that’s everlasting because I have flashbacks,” he says. “It’s a little bit scary. But it just reminds me how lucky I am to still be here.”

He adds: “I think it’s been an adjustment for my wife and my kids more than me. They recognise maybe how not so sharp I am.

“Maybe it has dented my confidence a little bit. Because when you go through something like that, it can play on your mind a little bit as much as you try and stay positive.

“For them, it’s not as easy to forget, because they nearly lost me.”

‘Writing the book was therapy’

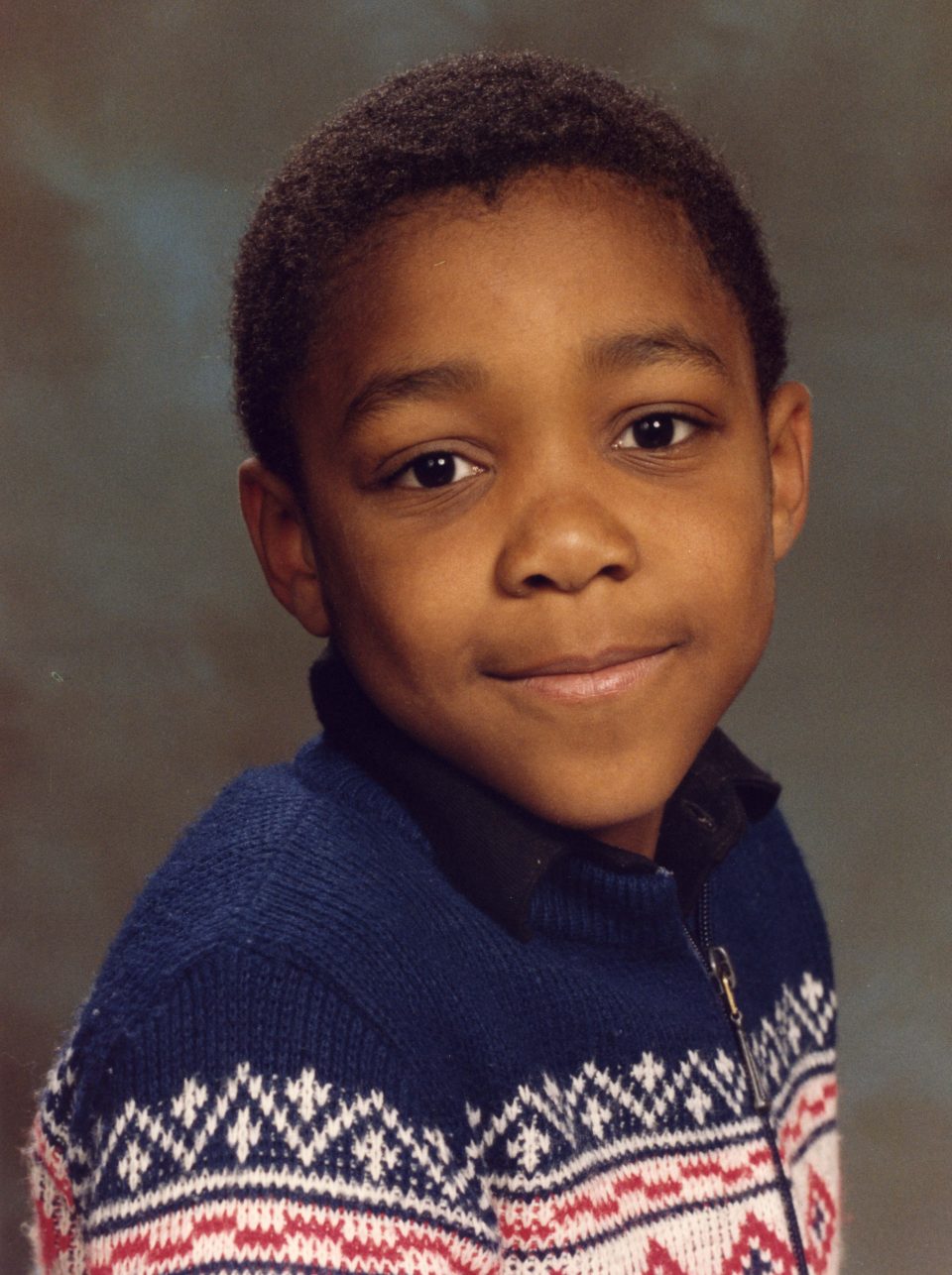

Campbell’s memoirs recount his rise from a single-parent upbringing in Manchester’s roughest areas to becoming one of Britain’s most decorated and popular track athletes, and an MBE.

Reliving his struggles – teachers who mocked his ambitions, everyday racism, the prevalence of drug cheats in the sport he loves – reaffirmed his fighting spirit.

“Writing the book was therapy as well,” says the 47-year-old, who lives in Wales with wife Clair and their children.

“It gave me strength in that I’ve come back from so many things in my life, that I actually could heal.”

Campbell threw himself back into work as soon as he could, running his supplements business, broadcasting for the BBC and coaching.

Since retiring as an athlete, his sprint training with rugby players and footballers has seen him work with Jonah Lomu and Sam Warburton at Cardiff, Andriy Shevchenko, Didier Drogba and Nicolas Anelka at Chelsea, and Danny Cipriani, Christian Wade and Eliott Daly as Wasps.

He helped Adama Traore at Middlesbrough and became close friends with Yannick Bolasie, who flew Campbell and family out to Portugal to work with him at Sporting Lisbon.

“Coaching was one of the things that I got back to quite quickly,” he says. “And it helped me to heal in a way because being around sports people, the energy – people want to get better.”

‘It’s important to dream – and dream big’

Campbell’s book devotes relatively little space, just six pages of epilogue, to his brush with death and its aftermath.

Naturally, he would rather be defined by his Olympic and World Championship medals and his European and Commonwealth titles.

But he also felt it important to underline the hardship he overcame on the way, which included the gangland murder of a close friend in Moss Side.

“Illnesses and things happen in life,” he says. “Once you’ve read the story of my life, you gain an understanding of how I was able to get back, because I’ve had so much adversity in my life.”

He adds: “It would be easy to say that the best bits were the bits with medals, but the start of the journey was where life was difficult.

“Growing up is where I gained the ability to dream big. Being told that I wouldn’t amount to anything, yet having a dream of going to the Olympic Games. It is a crazy dream.

“To think that not only did I go to the Olympics but I went to three Olympic Games. It just shows how important it is to dream. And to dream big.”

Campbell’s heroes: mum and Linford

Campbell cites his mum, Marva, who enrolled him at Sale Harriers after he shone on his first school sports day, as the biggest influence on his success.

“I remember phoning her after I won the Olympic silver [in the 200m at Sydney in 2000],” he says. “I expected her to go crazy. She just said: ‘I knew you could do it.’”

Linford Christie, whose tutelage and encouragement helped Campbell eventually fulfil his early promise, is also singled out for special praise.

“That’s why I was able to win so many medals, because I had Linford behind me who had the utmost belief in you achieving anything,” he says.

“I remember at one competition, he played the song ‘I Believe I Can Fly’. I said: ‘Come on Linford, I can’t fly…’. He said: ‘How do you know? You’ve never tried.’

“That World Championship, I won bronze in the 100m. Nobody expected me to do that.”

Taking a breath is an amazing feeling’

Since the pandemic, Campbell’s own coaching career has been on hold, although he hopes to revive it when possible.

His supplement business, PAS Nutrition – seemingly an attempt to keep his sport honest as much as it is an enterprise – and his broadcasting work, however, are going strong.

Lockdown has changed the pace of life, though, and his serious health scare has taken Campbell’s eye off other career goals.

“I always dreamt big, of the next thing. At the moment, I’ve stopped dreaming for the next thing,” he says. “I’m just trying to enjoy everything that’s happening now.

“The bleed on my brain really did make me reflect on a lot of different things. It made me value the extra time that I’ve got on this earth.

“Having gone through that life and death situation, just being able to take a deep breath once I wake up is an amazing feeling.”

Track Record is available from all booksellers, and signed copies can be ordered direct from the publisher: www.st-davids-press.com