When will the UK economy recover from coronavirus?

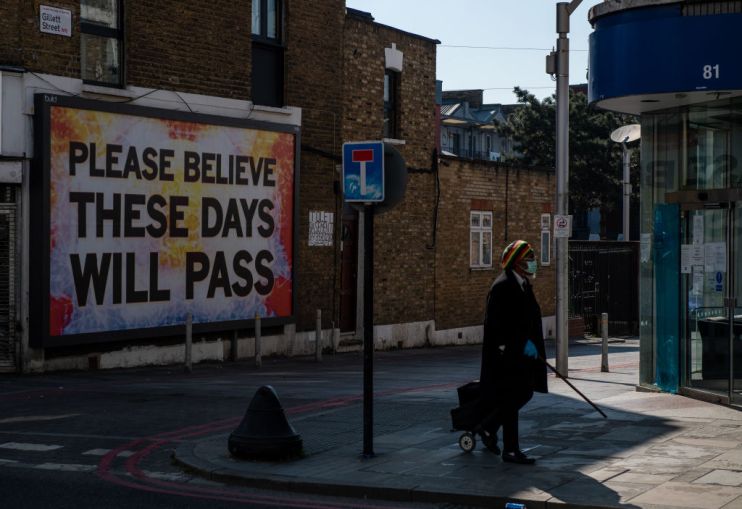

The UK economy is set for its worst contraction since at least the Great Depression this year as the coronavirus lockdown brings activity to a halt. There’s little doubt about that.

There is doubt about what comes next, however. Economists have made huge numbers of predictions, using an array of letters to describe the recovery. Some say it will be ‘V-shaped’, with a steep decline followed by a sharp rebound.

Others say the recovery will be ‘U-shaped’, with the damage from unemployment and company failures lasting longer. Some warn it will be ‘W-shaped’, featuring a rebound followed by another recession as coronavirus and the lockdown returns.

Economists are very careful to caveat their predictions heavily. “These are numbers that we’ve never, never dealt with before in our professional lives,” says Andrew Goodwin, chief UK economist at consultancy Oxford Economics.

But guesses are becoming more educated as the government clarifies its lockdown plans and more economic data emerges. So, what are some of the most clued-up people saying about the future of the UK economy?

Bank of England predicts ‘V-shaped’ recovery

The Bank of England last week produced a detailed report on the UK economy. Its main “scenario” says GDP would this year shrink by 14 per cent – the worst crash in 300 years. The UK economy shrank by just over four per cent in 2009 amid the financial crisis.

But crucially the Bank says the economy will pick up quickly at the end of the year and grow 15 per cent in 2021. It would then regain its pre-coronavirus size in the second half of next year. On a graph, that looks like a pronounced ‘V-shaped’ recovery.

The government’s unprecedented support packages such as the job retention scheme (as well as the huge injections of stimulus from the Bank itself) are central to its prediction of a sharp rebound.

The Bank assumes government support schemes will be unwound without a surge in unemployment or company defaults. Doing so is likely “to help prevent much longer-lasting damage”.

Economists agree that the recovery from this largely government-enforced slowdown will be quicker than after the financial crisis. But many say the BoE’s assumptions are overly optimistic.

Economists fear spike in unemployment

In particular, they say that a surge in unemployment and a wave of company failures are likely to cause more damage than the Bank expects.

Analysts agree that government support schemes have staved off an even worse collapse and will aid the recovery. This scheme sees the government pay 80 per cent of “furloughed” workers’ wages, until October. But many economists say that no matter when it ends, unemployment is likely to rise.

Ruth Gregory, senior UK economist at consultancy Capital Economics, says workers may well “find they don’t have jobs to go back to [and] more firms find they cannot balance the books”.

The BoE predicts unemployment will dip below four per cent by 2023. But Gregory says it is likely to stay higher for longer.

This would stunt the recovery in the UK’s dominant services sector. “The big concern,” says Goodwin, “is that you have a big increase in unemployment. Those people lose their skills, they drift out of the labour supply and it’s hard to get them back in.”

Capital Economics predicts GDP will fall 12 per cent in 2020 before rebounding 10 per cent in 2021. Gregory says the “scarring” means the economy will not reach its pre-coronavirus size until late 2022. That’s more than a year later than the Bank of England expects.

Adrian Paul, European economist at Goldman Sachs, says “packets of corporate insolvency” are likely to combine with persistent unemployment to cause “deep-seated scars”.

For Goldman, the UK economy will shrink 8.5 per cent in 2020 before growing seven per cent in 2021.

Second wave of infections threatens UK economy

Yael Selfin, chief UK economist at professional services giant KPMG, argues that coronavirus itself will weigh on the British economy until a vaccine or treatment is found. New cases have emerged this week in China, South Korea and Hong Kong.

A new wave of infections raises the prospect of a second lockdown. Therefore, any recovery is “going to probably be more of a ‘U’ or a ‘W’, depending on whether we have another lockdown,” Selfin says.

KPMG’s last prediction from the end of April says the UK economy will shrink by 7.8 per cent in 2020 and be held back by a second lockdown. Nonetheless, it assumes a vaccine will be developed in 2021 and growth will rebound by 8.4 per cent that year.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson at the weekend laid out a “roadmap” for gradually lifting the coronavirus lockdown. The government has encouraged some employees to return to work this week and hospitality businesses could open after 1 July.

But many economists say the psychological effects of coronavirus are likely to weigh on the UK public, even as restrictions are eased. Selfin says that social distancing is here to stay, whether government enforced or not.

This “means that almost no one will be able to operate back to normal,” she says. “It means that certain industries like the hospitality industry, international travel are going to be particularly badly impacted.”

UK economy faced with radical uncertainty

One thing economists can agree on is that huge levels of uncertainty make any predictions hostage to fortune.

The UK economy will be heavily influenced by the length of the coronavirus restrictions. Data out this week showed that GDP in March fell by a record 5.8 per cent because of just one week of lockdown.

And should the number of new coronavirus cases keep falling, the government still faces a tough task to reassure people that it is safe to go out and spend.

So will the UK economy rebound sharply from the coronavirus crash? The frustrating answer is that it is far too early to tell. Even the most important financial institution in the UK has little clue. The Bank of England’s report into the economy features the word “uncertain” 67 times.