What’s in store for the airline industry this winter?

Although every industry has suffered due to the coronavirus pandemic, few have been as hard hit as the world’s airlines.

At the beginning of the year, the idea of a world without global air travel was for most people a relic of a long-forgotten past, but seven months of extreme turbulence have flipped that notion on its head.

The combination of travel bans, quarantine regimes, and health concerns have seen passenger numbers nosedive around the world and have left the world’s carriers on life support.

Governments have spent £100bn so far on propping up airlines through the worst crisis the sector has ever seen, but with the traditionally unprofitable winter period to come, more will have to be done if the sector is to emerge unscathed.

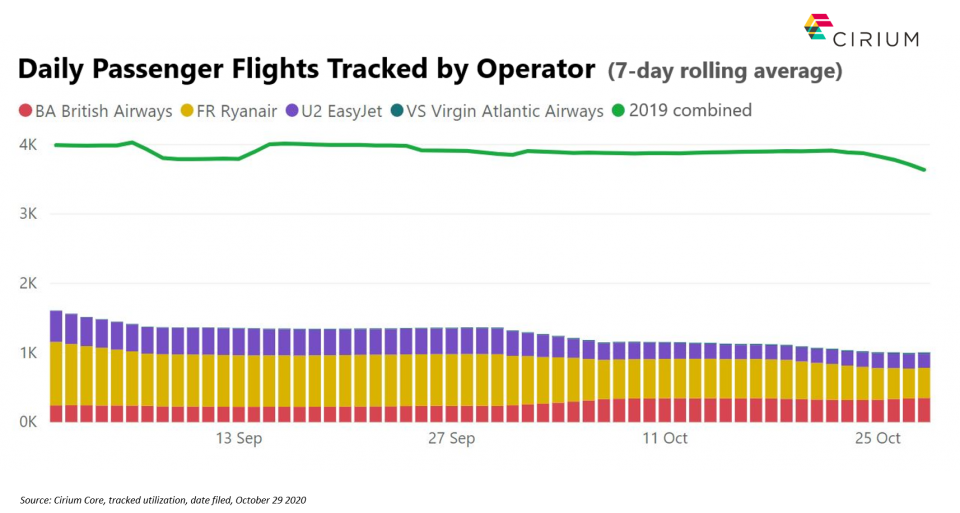

Earlier this month budget carrier Easyjet, which fell to its first ever loss, warned it would need more funding, while carrier group IAG, which owns British Airways, said it expected to fly a mere 30 per cent of capacity through the next three months.

Andrew Lobbenberg, aviation analyst at HSBC, said that all the focus now would be on cutting costs through the winter.

“For the companies it is a matter of who can hibernate most effectively through the winter with the hope that the environment will be more favourable next summer, although no one’s expecting it to come back with a bang”, he said.

First things first: Cash

On its own, however, that is unlikely to be enough. Lufthansa chief exec Carsten Spohr revealed that the German flag carrier was burning through nearly €600m a month, suggesting its €9bn state bailout is already being sapped by the demands of maintaining its fleet and crew.

“When we come to the spring all companies will need to strengthen their balance sheets because they will be in radically different place to what we expected six months ago”, Lobbenberg said.

Whether that money comes from private backers, or from a second round of state funding, remains to be seen – though probably depends on the country in question.

Across Europe, governments have rushed to prop up their airlines, with France, the Netherlands, Italy, Portugal and Norway all providing financial support of some kind.

It’s a very different story in the UK, where, despite early promises of sector-specific support, airlines have largely been left out in the cold by Chancellor Rishi Sunak.

BA, Easyjet, and Ryanair have all drawn down between £300m and £600m from the Bank of England’s emergency funding, but all raised extra equity to cope with the collapse in revenues.

Having turned down Virgin Atlantic for a £500m rescue deal the first time, could ministers now be tempted to reach into their pockets?

Julie Palmer, partner at restructuring experts Begbies Traynor, thinks not. “The challenge of going back to the government at the moment is that the pot is getting rather dry”, she told City A.M. .

“Politicians may be thinking, ‘Why support an industry if there’s going to be a long-term change to that industry’s model of business anyway?’ If it’s not going to return to historic levels until 2025 anyway, then you’re looking at very long-term support, so do you instead say that we need to let this model correct itself and reduce down to the level that it is going to be going forward?”

Before the Open newsletter: Start your day with the City View podcast and key market data

And independent consultant Chris Tarry warns: “Not everybody wants to invest in airlines, and not everybody has to.”

Failures on the horizon

So is it therefore inevitable that some airlines will go bust as a result of the crisis? For Lobbenberg, it’s a done deal, but he thinks it will be smaller, secondary carriers which collapse, and not the bigger names.

A lot of this is down to securing connectivity for when demand does eventually come back. “Frankly, smaller carriers are not going to deliver the kind of international connectivity that a global country wants”, he says.

Yet some bigger names may be under threat as well. Even before the crisis analysts had raised concerns about the viability of Norwegian – which is in talks with officials over temporary state ownership – while others cited Virgin Atlantic as another candidate for failure.

Both are heavily exposed to the lucrative transatlantic market, which all but shut due to the continued ban on entering the US.

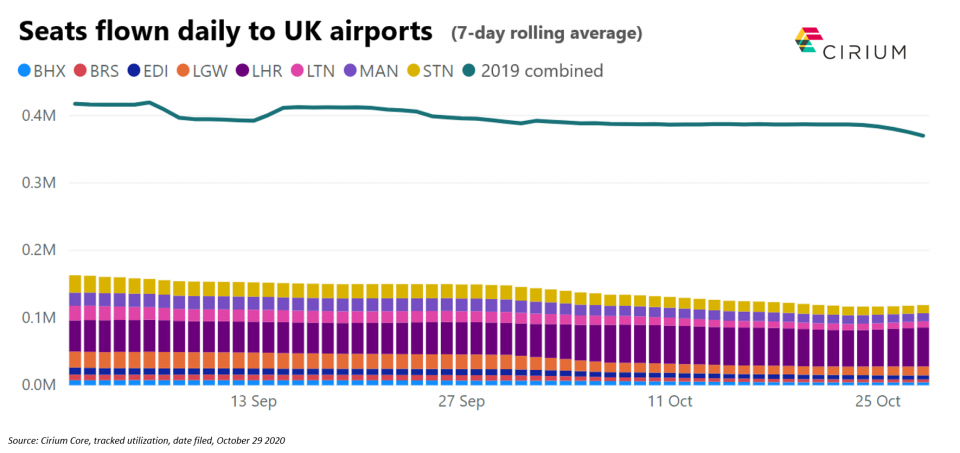

Figures from Heathrow showed that passenger numbers from North America fell 94.8 per cent year-on-year in the last quarter, and though the industry has pleaded for a travel corridor between London and New York to be trialled, any such scheme still seems months away.

A time for opportunism for airlines?

Amid such uncertainty, it’s time for carriers to get creative, said aviation consultant John Strickland.

“Airlines are going to have to be far more opportunistic about where they fly. With all that capacity available, in terms of both aircraft and crews, either you have to find viable uses or take tough decisions about disposals or redundancies”.

The more nimble you are, the better, he reckons, and the performance of one carrier in particular suggests this is the case.

Hungarian budget flier Wizz Air was the first to restart flights from the UK back in May, and has opened 12 new bases even while the pandemic clipped the wings of other carriers.

A new subsidiary based in Abu Dhabi will also open up the Middle Eastern and African markets to the carrier, which has previously focused on Europe.

Palmer added that she expects smaller operators to use that nimbleness to “nibble away” at the bigger players – and for private jet travel to become increasingly popular as well.

“Nature hates a vacuum and where there is a vacuum somebody will find a way to try and fill some of that space”, she said.

Such opportunism is perhaps best typified by plans for a surprise relaunch of Flybe, which fell into bankruptcy as the pandemic reached the UK in March.

The regional flier operated around 36 per cent of all domestic UK flights – 7,500 a month, according to aviation data analysts Cirium – and will be hoping to claw back its monopoly on many of those routes.

Some are more doubtful, however. “I’m surprised that there is an attempt to resuscitate the airline. It’ll be a question of whether there are enough of these routes around that perhaps could on a smaller scale turn to profit, but I’ve got quite a high degree of scepticism”, said Strickland.

The next five years?

Although the way back is long, analysts were unanimous that demand would return.

Most airlines have forecast that it will take them until 2024 to get back to pre-pandemic passenger levels, but Lobbenberg said that it could well be politics, not the virus, that defines the future shape of the industry.

“The future is going to swing on where the broad political debate goes between globalisation and nationalism”, he said.

“If we do move back towards a more global society which could happen with a change of regime in America then all the debates about ownership could drop away. Alternatively, what we absolutely do see in the very short term is an increase in nationalism and an anti-globalisation push, which could lead to further restriction for global airlines.”

And closer to home, the challenges of leaving the EU could well see the UK reconsider the emphasis it puts on the country’s airlines, Tarry suggested.

“It is impossible to understate the importance of air transport for economic development in the world we used to know and the world we hope to know again. There comes a point when the government will have to determine what its role is in supporting strategic industries like aviation.”

But in the meantime, it’s going to be a very bumpy ride.