What will the Budget mean for the UK economy?

The dust is starting to settle on Chancellor Rachel Reeves’s first Budget, but economists will be debating its likely impact for months to come—if not years (lucky us).

What’s not up for debate is that this was an important Budget.

“This budget delivers one of the largest increases in spending, tax and borrowing of any fiscal event in history,” Richard Hughes, chair of the OBR said.

As a result of the government’s policies, the size of the state will rise to 44 per cent of GDP by the end of the decade, five percentage points larger than it was pre-pandemic. The tax take will rise to over 38 per cent of GDP, its highest ever level.

Yet despite this big increase in the state’s size, the OBR’s medium-term forecasts barely moved. Growth will be a little higher than expected in the short term and a little lower than expected thereafter.

The Chancellor may be feeling a little frustrated.

The government announced tax rises worth just over £40bn, which will help fund an increase in public spending worth just over £50bn.

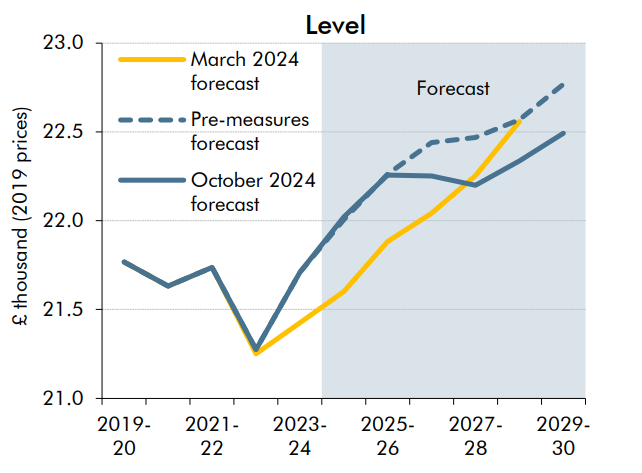

Despite the government’s rhetoric, this will largely be funded by households. On the OBR’s estimates, real household disposable income will be 1.25 per cent lower by the start of 2029 than in its March round of forecasts (although still higher overall).

The OBR suggests around 85 per cent of this difference can be “explained by policies announced in this Budget”.

“This implies shifting real resources out of private households’ incomes in order to devote more resources to public service provision.”

Will Labour hit working people?

But wasn’t Reeves meant to be sparing ‘working people’?

Well, that’s not how it will turn out. It turns out that it is quite difficult to raise tens of billions without, somewhere down the line, raising taxes on ‘working people’ (where else would it come from?).

The second component of the Chancellor’s spending plans was a big increase in public investment.

Public investment will be more than £100bn higher by the end of this parliament, staving off the cuts which had been pencilled in by the previous government.

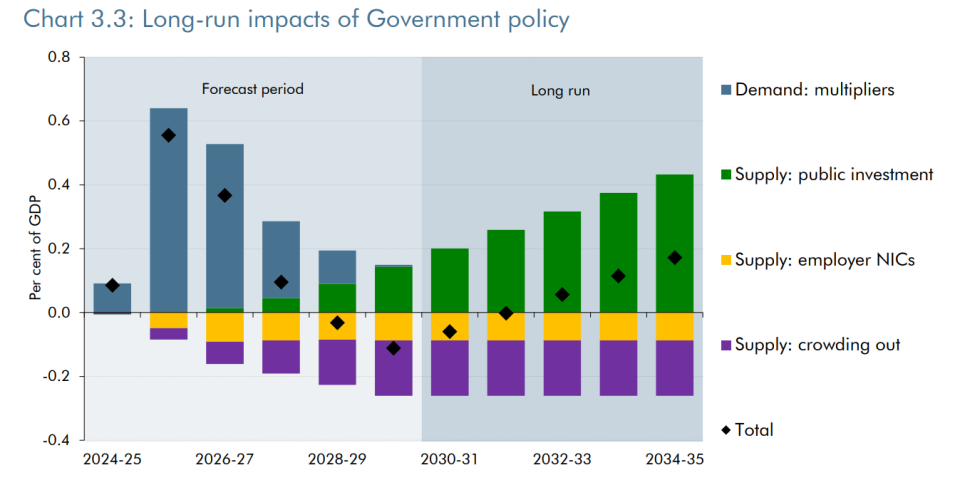

The OBR gives two perspectives on the increase in public investment with differing time horizons.

These perfectly align with the left-wing and right-wing views on public investment.

Looking five years ahead and the impact actually appears to be negative, with an increase in public investment crowding out business investment.

Extend the time horizon, however, and the impact swings positive again despite the impact of crowding-out, as an improved capital stock of makes itself felt.

This is why the medium-term growth outlook looks disappointing.

The government has essentially taken more money from households and put it into public services. The increase in public investment will come at the expense of private investment. It all nets out.

Will Rachel Reeves’s plans work?

The real question is what’s going to happen in the long term?

There is a compelling argument that the quality of the UK’s public services is a significant impediment to economic growth.

The most obvious example is the big post-pandemic increase in people out of work due to long-term sickness.

Re-integrating half of those people into the workforce could boost output by three per cent, BCG estimate, which is a huge increase. But it will cost money.

A strong growth case can also be made for investment.

Many economists, including Mark Carney and Andy Haldane, have been calling for an increase in public investment for years.

Increasing investment should both improve public service delivery and improve the economy’s physical infrastructure.

According to the Resolution Foundation, the UK has fewer hospital beds per person than all bar one OECD country.

Brits also spend more time commuting than all bar two rich economies due to under-investment in travel infrastructure.

Increasing public investment might crowd out private investment in the short-term, but if the government invests in the right projects, it will improve the economy’s productive capacity.

So where does that leave us? In his speech on Monday, Prime Minister Keir Starmer spoke of the “power of government” to improve the UK’s growth potential.

The government’s hope is that by taking more from the private sector now, it can rebuild the fabric of the economy.

This is clearly a risk. “A lot hinges on how well the government spends the money,” Paul Johnson director at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, said. Asking more from businesses and households may also weigh on growth.

But doing nothing is also a risk. The UK’s growth trajectory is poor and its public services are in dire straits. Time will tell if Labour’s approach is right.