What we learned from this year’s Booker Prize

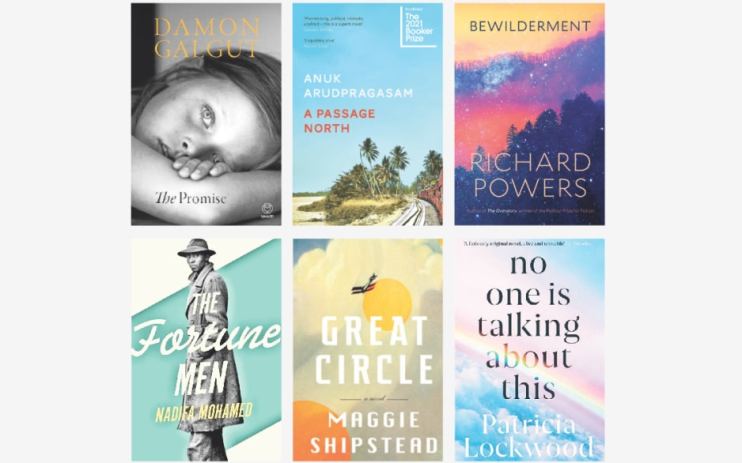

Bookies favourite Damon Galgut was awarded the Booker Prize last night for his novel The Promise. Set in his home city of Pretoria, it tells its story through four funerals. Here’s what we learned from the result.

A nomination won’t make you rich overnight

Prior to the announcement, the best selling book on the nomination list was Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This at 9,541 copies, with The Promise placed second with 8,844. While nudging the 10,000 copies mark is no mean feat, neither will it translate to a life-changing sum. With the average royalty on hardbacks being roughly 10 per cent, these authors will have, thus far, made less than a grand for their prize-nominated efforts. This is more a comment on the state of the publishing industry than the Booker prize or these particular authors – to make it onto the Sunday Times Best Seller list you only need to shift in the region of 5,000 books, which hints at the uphill struggle most authors face, especially those working in fiction, where advances are rarer than hen’s teeth for those without previously published work.

The Booker has had enough of controversy

Many people remember the 2019 Booker awards, although few think back on them particularly fondly. The literary world reacted with bemusement when Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo were announced joint winners in 2019, despite joint winners having been banned in 1992 (there were two instances previous to this). Rather than elevate the work of two great female authors (male winners have outpaced women by two to one since the inaugural 1969 event), the decision seemed to detract from both. This year no such controversy occurred with the favourite storming home.

Americans still dominate

Seven years since the Foundation announced its decision to admit all novels authored in the English language, books by Americans continue to dominate the selection process, making up three of the 2021 prize’s six shortlisted writers: Patricia Lockwood, Richard Powers and Maggie Shipstead. When the decision was announced in 2014, over 30 publishers signed a letter complaining that the move would usher in a “homogenised literary future”. Many feared it would impact on the diversity of the prize – which had originally only been open to writers of The Commonwealth, Ireland, and South Africa – or that it would lose its distinctiveness. But tensions have simmered. The two American winners thus far have been Paul Beatty’s The Sellout, in 2014, and George Saunders in 2017 for Lincoln in the Bardo, both of which were warmly received, and went on to become bestsellers.

Digital is king

IIn the week leading up to the prize-giving ceremony, the Award’s website premiered six short films of actors reading extracts from the shortlisted novels. Embracing the vogue for short format video could be seen as welcome evidence of the Foundation modernising. Last year’s event, in which Shuggie Bain’s Douglas Stuart triumphed, was entirely digital, and it seems that some of the lessons have been kept; harnessing the creativity that comes with using the visual to enliven the written word.