What we know – and don’t know – about Rachel Reeves’ spending and investment plans

Rachel Reeves’ speech at the Labour conference this week had one driving thread: boost investment.

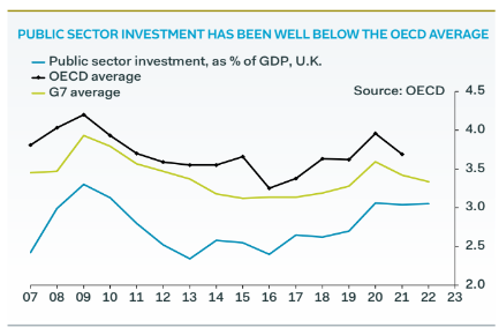

She highlighted that the UK invests a lower proportion of its GDP compared to other advanced economies, pledging to lift investment to the rate “needed to compete internationally”.

Analysts at Pantheon Macroeconomics suggested this could see the UK’s rate of public sector investment rise from 2.9 per cent to 3.5 per cent, the OECD average in the 2010s.

While Reeves has pledged not to borrow to fund day-to-day spending, the party argues that “it is essential for our future prosperity that we retain the ability to borrow for investing in capital projects which over time will pay for themselves.”

The hope is that government can ‘crowd in’ the private sector, helping to lift the overall level of investment. Labour has committed to investing billions in green projects, with pledges to hit £28bn a year by 2028 if it wins the next election.

But bond yields all over the world have spiked in recent weeks, partly over concerns that governments will have to borrow billions from financial markets to fund their investment programmes.

So is there a risk that Reeves’ plans will cause a market meltdown?

The short answer is no. Many economists agree that the UK needs to raise the level of investment. Low levels of investment have hamstrung productivity growth, contributing to the unusually slow growth seen since the financial crisis.

“The overarching message from Rachel Reeves’ speech that the UK needs to raise investment as a share of GDP is a sensible one,” Ruth Gregory, deputy chief UK economist at Capital Economics said.

Samuel Tombs and Gabriella Dickens at Pantheon Macroeconomics said the sense that the UK needs more investment means investors should “look more favourably on unfunded infrastructure spending” rather than unfunded tax cuts.

Unlike tax cuts, public sector investment also does not undermine the state’s net worth, a measure which aims to summarise what the government owns and what it owes

However, Tombs and Dickens cautioned that Reeves would struggle to meet her commitment to cut the debt-to-GDP ratio over the lifetime of a parliament.

The overarching message from Rachel Reeves’ speech that the UK needs to raise investment as a share of GDP is a sensible one

Ruth Gregory, deputy chief UK economist at Capital Economics

Higher interest rates are likely to add an extra £15bn to government debt in five years time, according to Pantheon calculations. Moreover, while government investment boosts GDP in the short term, they pointed out that the GDP boost wanes over time while the cost has a “lingering upward impact on the debt stock”.

“It is hard to see how a Labour government could raise investment to the OECD average while also hitting its target for the debt ratio to be falling,” Tombs and Dickens said.

To get debt levels falling while boosting investment, they predicted taxes would have to rise.

Torsten Bell at the Resolution Foundation agreed that taxes would have to rise if Rachel Reeves followed through on her spending plans, but suggested the true consequences of raising levels of investment would be more wide-ranging.

“All we talk about in British politics is the public finances – but becoming a higher investment nation has a much bigger consequences for the UK economy as a whole,” he tweeted.

“It’s time those of us who want more investment to focus on the consequence for consumption”.

Bell suggested that to lift the rate of investment without relying on borrowing, consumption would have to fall as a share of GDP. In essence, present spending needs to be postponed to enable greater investment.

“If you want lots more infrastructure built and homes retrofitted you need more construction workers – those workers will come from somewhere (maybe fewer staff in pubs),” he suggested.