What our politicians can learn from the Hunger Games rules of persuasion

PANEM today, Panem tomorrow, Panem forever.” You need to watch the chilling new teaser for the next Hunger Games movie, Mockingjay. Its cool irony confirms the series’s remarkable journey from minor young adult diversion to cultural milestone. The series of thrillers is no cinematic masterpiece, but 30 years on from 1984 it is helping inoculate a new generation against the horror and seductions of tyranny.

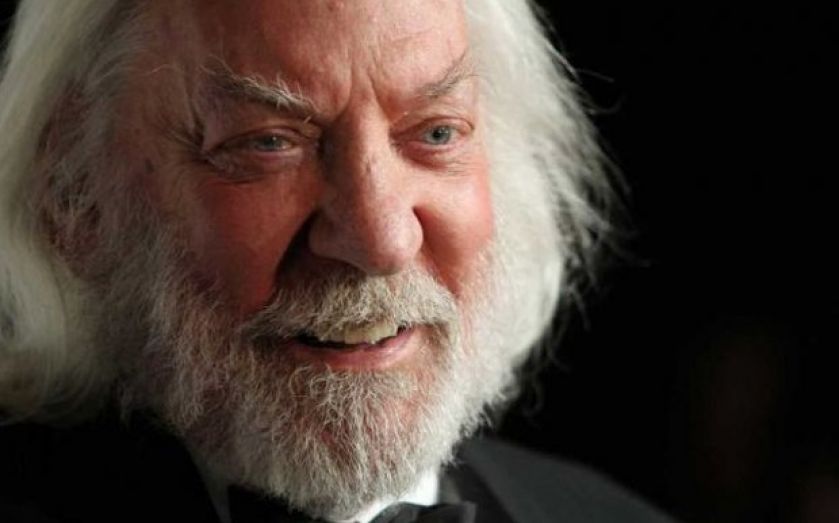

On its surface, the trailer is a political broadcast on behalf of the enemy. The autocratic President Snow, clad in stylish white, murmurs of the elegance of his system while words like prosperity and unity flash up on the screen. Next to him, Hunger Games survivor Peeta Mellark stares beatifically into the middle distance.

But it is all a mirage. Those who know the story will appreciate that drugs have reduced Peeta to a government stooge, just as they know Snow’s superficial glamour for a savage lie. And as his broadcast continues, everyone can hear the violent threat that underpins his power. “If you resist the system, you starve yourself. If you fight against it, it is you who will bleed.” Instead of Orwell’s boot stamping on humanity forever, it is the unending rule of Snow and his kind that is rubbed in our faces as it concludes.

This disturbing fragment is also a neat demonstration of Aristotle’s three modes of persuasion. In his Rhetoric he identifies them as logos, pathos and ethos: the logical case of the speech, its emotional effect on the hearer and the credibility of the speaker. In the Mockingjay trailer, Snow’s brutal logic blends with the unsettling emotional impact of his reassuring tone to turn the spotlight on his ethos, drawing us to see past his surface charm to the despot beneath.

Our own political leaders are more Punch and Judy than pantomime villains but the triple test still enables us to identify their strengths and weaknesses. Clegg? Ethos in tatters thanks to a series of broken promises. Miliband? Too weird to gain the electorate’s emotional trust, even before they consider the illogic of a policy platform that reads like a seventies mixtape. Cameron? Struggling to capitalise on the strong logic of economic recovery thanks to a bland air of superiority that’s hard to empathise with. Plus his equivocations over European renegotiation hardly suggest a man of character.

Against this dispiriting lineup, it’s easy to see why Nigel Farage of Ukip has done so well. Voters can empathise with a man who speaks like a human being, enjoys a pint and earned his money working in the private sector. Further, they believe his bluff persona honestly reflects a clear and consistent ethos.

The logos of Ukip’s policy platform remains unproven: the credibility of its manifesto for the upcoming election will be a crucial test. But the other parties seem to have forgotten that, without fighting on all three of these rhetorical fronts, a population increasingly suspicious of slick political messaging will take their best efforts for a snow job.

Marc Sidwell is managing editor at City A.M.