| Updated:

What makes us remember some things, but forget others? It’s all in the dendrites

There seems to be little reasoning behind the mind's decision to remember some experiences and forget others. If someone asked you to recall what you had for lunch two Mondays ago the chances are you wouldn't have a clue, but an inconsequential conversation you had with someone around the same time may well have stuck in your head word-for-word.

For the first time, two researchers at Northwestern University in the US have been able to differentiate between the cellular processes of simply “computing” an experience and actually storing it as a memory.

Using a specially built laser scanning microscope with the ability to image brain cells on multiple planes, they peered into the brains of living animals to see exactly what was happening to individual cells as the animal navigated a virtual reality maze they had created.

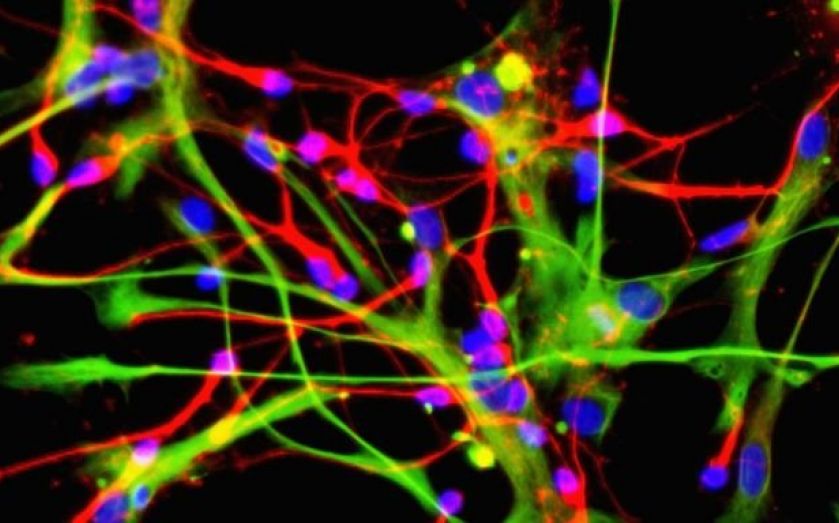

Each lit-up structure in the images they took indicated a cell firing off signals, and the activity of these cells represented an animal's experience in terms of where was is in the environment. They found that whether a cell stored an experience or not depended on the activity of its dendrites.

These highly-branched, tree-like extensions extrude from the cell body and are crucial for transmitting information once it has been received from another cell in the form of an electrical signal.

Scientists have long believed that the tasks of computing and storing information are connected – that when cells compute information, they are also storing it, and vice versa. But the new study disputes this popular opinion, since the researchers observed that dendrites are not always activated during an experience.

Instead, they saw that cell bodies were sometimes activated alone, and that in these situations a lasting memory of the experience was not formed. This suggests that the cell body represents an ongoing experience, while dendrites, the treelike branches of a cell, help to store that experience as a memory.

"There are a lot of theories on memory but very little data as to how individual cells actually store information in a behaving animal," explained Daniel Dombeck, co-author of the study.

"Now we have uncovered signals in dendrites that we think are very important for learning and memory. Our findings could explain why some experiences are remembered and others are forgotten."