I went up a mountain in Sri Lanka to meet a reclusive mystic and here is what I learned

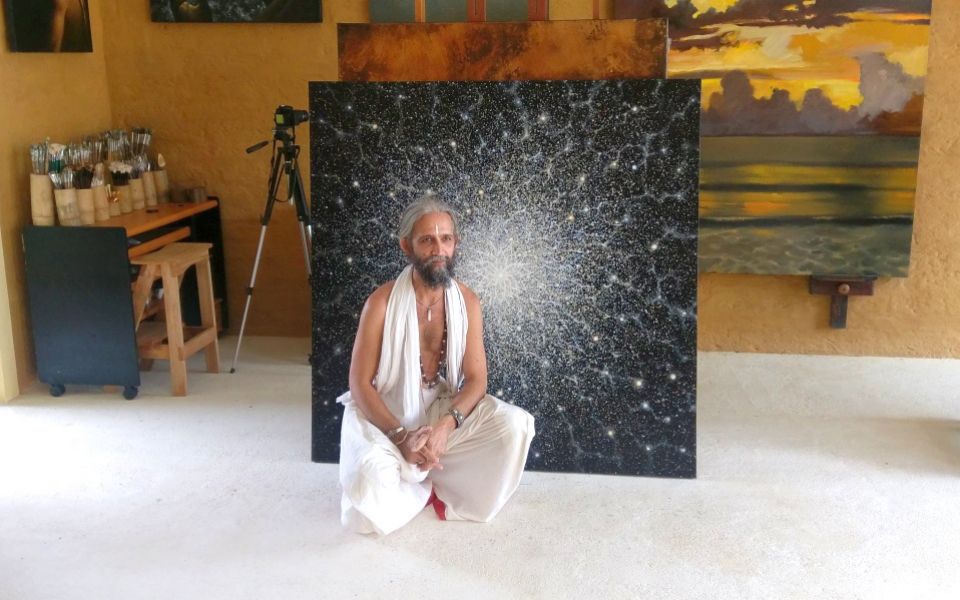

Somewhere high up in the hills surrounding the town of Kandy in Sri Lanka, there lives a man called Rahju. An artist, spiritualist and musician, Rahju practices meditation while riding along coastal roads on his motorcycle.

His paintings are inspired by the writing of Buddhist philosophers and the intergalactic observations of the Hubble Space Telescope (as well as, if I had to go out on a limb, a not-insignificant amount of hallucinogens). At one point he produced a sitar from thin air and strummed out a kickin’ tune, before regaling us with an anecdote about the time Ravi Shankar received rapturous applause from a stoned audience, who mistook his idle string tuning for an avant-garde musical experiment.

If you came across Rahju in an east London bar, you’d think he was laying it on a bit thick. The guru garb, the whisper-soft voice, the effusively relaxed vibe, the pervading sense that there is nothing in this world to worry about but the here and the now. But here, on the top of his mountain (I assume that the mountain belongs to him, and that it somehow belongs to me now, too) he is in his element. He makes sense. It’s only when surrounded by the profound natural beauty and spectacle of the rolling, sea-green Sri Lankan landscape that this recluse begins to seem an even remotely plausible character.

We had arrived at Rahju’s studio by racing bright red and blue tuk-tuks up a steep jungle path, having earlier ascended from the ancient shrines and dagobas dotted about the Temple of the Tooth, a sacred site that’s said to house the relic of the actual, honest-to-goodness tooth of the Buddha. Earlier that day we’d wandered the Royal Botanical Gardens and saw fruit bats the size of small dogs flying overhead, their four foot wingspans casting primeval shadows that raced across the shining wet lawns. Minah birds poked about in the dirt, in search of whatever it is minah birds like to eat, while littering the ground were preposterous, ass-shaped coco de mer nuts, the largest and most gluteal looking nuts in the world.

This is the kind of place that’s so unnervingly picturesque you find yourself speaking in hushed tones, as though a single loud noise could bring it all crashing down and catapult you back to Heathrow Terminal 5.

These nut-speckled gardens and this mind-expanding hermit were two stops on a 500 kilometre journey I took around Sri Lanka’s southwestern quarter, beginning at the tropical Indian Ocean coastline north of Colombo, before climbing eastwards into the mist-soaked tea plantations at this teardrop-shaped island’s highest altitudes. During the long train ride upwards – in a first class car populated exclusively by backpackers – Jurassic World played on the carriage’s television screens, providing an incongruous soundtrack of gunfire and velociraptors as we clattered and wound our way higher and higher into the serene green hills.

On the platform I played with two feral puppies until a woman became so disgusted she gestured to a tap and demanded I wash the vermin from my hands, as if I’d just been caught playing with a pair of rats. Wild dogs lined the streets everywhere we went in Sri Lanka, sleepy and benign, and mongrelised over generations into the perfect median shape, size and colour of a dog. Buddhists operate free neutering centres in order to keep their numbers down.

My route joined the dots between five boutique hotels: The Kandy House, Living Heritage Koslanda, The Last House, Kahanda Kanda on Koggala Lake and the Fort Bazaar Hotel, in the predominantly Muslim fort town of Galle. For some of the owners of these properties, many of them British migrants, the drawn out civil war and global recession left them and their investments in a state of limbo, frozen in time and awaiting a change in fortunes. There was a whiff of cabin fever about some of them, a desperate air that lingered just behind the hospitality, like those infrequently seen friends who have retired to the countryside and demand to know what’s happening back home, back in the city with all its people and flashing neon lights.

For a hibernating hotelier, there are worse places to be exiled. Besides, after decades of uncertainty those fortunes are finally changing, tourists are returning and business is invigorated. New small hotels are opening that cater to the luxury, eco-minded traveller rather than the gap year backpacker. The focus on classy and low-impact boutiques is partly driven by tourism regulations restricting the number of high-rise hotels built along the protected coastline, in an effort to keep Sri Lanka from jamming up with chains and turning into Thailand 2.0.

That’s not to say people aren’t arriving in droves. The end of the quarter-century long war in 2009 saw the terminally declining number of arriving tourists drop to 450,000. By 2015 the country was welcoming almost 1.8m visitors per year. Sri Lanka is seizing upon an opportunity to properly shape the development of its newly returned tourist industry. Carefully managed, its future profile as a travel destination aims to be one of quiet refinement and sophistication.

The jagged road to the quiet refinement of Living Heritage Koslanda gives the impression that they don’t actually want any visitors, and the reward for arriving intact is a spectacular oasis which, considering its location amid some already quite dramatic surroundings, feels a bit like over-egging the pudding. This is the kind of place that’s so unnervingly picturesque you find yourself speaking in hushed tones, as though a single loud noise could bring it all crashing down and catapult you back to Heathrow Terminal 5.

Wild elephants wander between the villas at dawn, silent and looming like the ghosts of friendly grey houses, and monkeys – who smash roof tiles and are considered a scourge even more heinous than wild puppies – arrive in rowdy gangs to strip the fruit trees long before they’re ripe. On our first morning we walked through the forest to a pool beneath a waterfall, where we stripped off and swam in the cold water, like soon-to-be-murdered teenagers in a horror film. I avoided decapitation by chainsaw, but I was briefly menaced by a cow on the way back.

The food is exceptional everywhere, but especially here at Living Heritage, where it’s prepared by a hotshot 21-year-old chef who is claimed to be something of an undiscovered culinary prodigy. His food certainly bore the notion out. My diet consisted mainly of aubergine and cashew curries with rice, and egg hoppers (a basket-shaped pancake with an eggy surprise inside) and dosa for breakfast. Breadfruit, beetroot and jackfruit all featured heavily too. Relatively hard to come by in the UK, a fresh jackfruit is liable to fall out of a tree and bludgeon you to death at any time and almost everywhere you go in Sri Lanka. It’s the stuff vegetarians keep insisting is indistinguishable from pulled pork when cooked (it isn’t), and it is delicious.

The following day we rode bikes through paddy fields, the hot and sticky air about as wet as it can be without turning into actual liquid. It was Poson, the national full moon holiday celebrating the anniversary of the arrival of Buddhism on the island, and so everywhere we went tiny children would flag us down to give us free snacks. Poson is essentially the absolute opposite of Halloween. Villages set up roadside food stalls called dansala where anyone can come and eat whatever they like.

Galle on the south coast is a town built by the Portuguese in the 16th century and later fortified by the Dutch, where colonial architecture meets south Asian culture amid a multi-ethnic, multi-religious population. That its giant stone ramparts shielded it from the 2004 tsunami is a tempting metaphor for strength through diversity, or perhaps the benefits of surrounding yourself with very large walls. The final stop here was the Fort Bazaar hotel, a renovated merchant’s villa built around a central private courtyard, where they’ve got special doorbells by the bed to summon champagne – though the buzzers were sadly disconnected when I stayed, pending approval of a liqour licence by the tourism board. I poked them all the same, just in case.

With its souvenir stalls awash with tourists and shoppers, Galle feels like many other old towns around the world, its roads polished smooth by the footfall of cruise ship visitors and honeymooners. It’s here that you get the clearest sense of a finger having been taken off Sri Lanka’s pause button – that a giant cog somewhere has started whirring once again. Back up in the mountains, with nobody but Rahju for company, you’d hardly guess that anything had changed at all.

Scott Dunn offers a seven night luxury tailor-made trip to Sri Lanka from £2,495 per person. This includes flights with Sri Lankan Airways, luxury boutique accommodation, a selection of experiences and a private driver and guide throughout. For more information please visit scottdunn.com or call 020 8682 5060