We need to talk more about lithium – UK risks supply shortfall to feed its electric car ambitions

The future of Britain’s electric vehicle (EV) sector is far from certain.

Automakers were overjoyed this month to read reports that said the UK had likely pipped Spain in the race to secure a multi-billion dollar ‘gigafactory’ in Somerset, built by Jaguar Land Rover owner Tata – touted as vital in changing the fortunes of Britain’s nascent EV industry.

But late last week and AMTE Power – the battery firm with plans to build a £200m gigafactory in Dundee – threatened to move the future plant overseas unless the government offers greater financial incentives to stay.

AMTE’s warning shots were followed just two days later by a dramatic announcement that the firm needed urgent cash in “no less than four weeks,” amid a shortfall, which saw its shares plummet 70 per cent and triggered memories Britishvolt’s dramatic collapse earlier this year.

However, amid the ups and downs of Britain’s attempts to bolster its EV manufacturing capacity, another area of concern has crept into the picture; the ability to supply and process the vital minerals used in electric batteries.

Lithium-ion batteries are the most widely used technology as of today, making lithium gold dust in the EV race.

Eighty to ninety per cent of its demand stems from its use in producing the batteries for electric cars.

Currently, according to energy research firm Rystad the UK would need between 53,000 and 70,000 tonnes per year of the silvery-white metal to meet EV demand in 2030.

However, it is currently only on track to have only secured around 35,000 tonnes by the end of the decade.

And while the UK published a Critical Minerals Strategy in July last year, the only tangible developments since then have been the launch of a new intelligence centre, to study the minerals the UK is sorely lacking, and the meeting of a new taskforce which does not appear to have done anything.

Mike Hawes, chief executive of the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders told City A.M. that although the UK has some lithium supply, this is “not enough to sustain our current, or indeed future, electric vehicle battery production ambitions.”

Hawes said that to combat this shortage, the government needs to invest in the domestic lithium processing capabilities, while also working on developing new trading arrangements with countries that have an abundance of the substance.

“This approach would help shore up UK manufacturing competitiveness at a critical moment, as countries around the world race to secure the future of their automotive sectors as they undergo a massive green industrial transformation,” he said.

Ben Nelmes, who heads up the EV research group NewAutoMotive, cautioned that “if we’re more reliant on supply chains that are further afield, it’s going to push up the cost of the vehicles because you’re going to have to transport batteries or cells.”

“Not having those supply chains close to home would be really bad [and] it means Britain would miss out on the opportunities of this technology, because it will remain a bit more expensive here than it is in other places,” Nelmes said.

UK needs to make new lithium alliances

Lithium and minerals experts contacted by City A.M. echoed the automotive sector’s concerns, highlighting Europe-wide challenges in supplying and processing the metal as the bloc faces fierce competition from China, which dominates the market.

Like Hawes, they argue that bolstering trade agreements with big lithium extractors, particularly Australia and South American nations and boosting home processing capabilities, would help the UK handle the competition from China.

James Ley, senior vice president of energy and metals at Rystad told City A.M. that “the problem is that, at the moment, China is the absolute king of processing.”

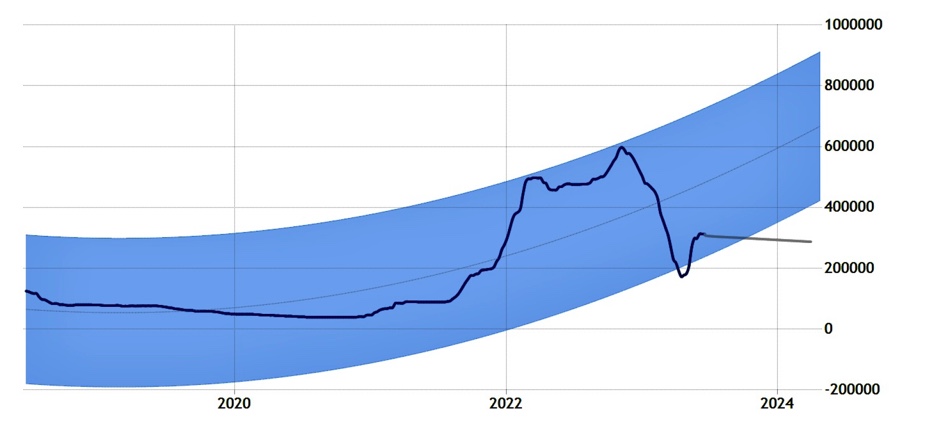

Lithium trading prices and 2024 forecast (CNY/T)

“Around 60 to 90 per cent of their global processing share is in China… China’s doing all this processing and therefore the car plants in Europe and gigafactories in the UK would have to go to China to get the processed material,” he explained.

Dale Ferguson, technical director at Savannah Resources said the “supply-demand gap” as EV production ramps up “really starts to increase from 2025 onwards.”

He argued it was “clear to everybody that there’s probably not enough supply in Europe” to “meet all the demand.”

“There needs to be more assistance within Europe for the miners and more help to try and get this product into the market because without that raw product, the rest of the value chain will be challenged.”

A spokesperson for the Department for Business and Trade said: “We are working hard on to increase our critical minerals supply – signing agreements with Canada and Australia on supply chains and engaging with our counterparts on the Minerals Security Partnership, International Energy Agency and G7.”

The spokesperson added that the government had taken steps to “improve supply chain resilience,” and is “supporting several lithium extraction and refining opportunities” through its Automotive Transformation Fund – which supports UK companies such as Cornish Lithium and British Lithium.

Whether or not Somerset gets its much-anticipated gigafactory or AMTE survives and sticks with Dundee – the government is coming under increasing pressure to do more to secure the UK’s lithium supply to help Britain achieve its electric vehicle ambitions.