We need a government that gets business, not businessmen running government

The idea that business leaders can transform the way government works didn’t start with Elon musk, but success in politics demands different skills to entrepreneurship, says Eliot Wilson

Business feels let down by the current government. Before the general election, Sir Keir Starmer and his shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves, staged an updated performance of the late John Smith’s “prawn cocktail offensive” of the early 1990s, when he worked to reassure and woo the City of London that Labour could be trusted with the nation’s finances.

Starmer and his colleagues tried hard. Former Thatcher devotee and friend of Liz Truss, PR trouper Iain Anderson, found his principles pulling him in a new direction and was commissioned to review Labour’s relations with business. The result was the anodyne A New Partnership, which said very little but said it over 36 glossy pages. The party also published Financing Growth, a plan to support the financial services sector. Tax rises were ruled out, feathers diligently smoothed. Everything would be all right.

I wrote at the time that it was a sham, and that Labour remained fundamentally dirigiste and uncomfortable with free enterprise. But some lessons have to be learned the hard way: government borrowing costs have hit a 27-year high, investors are losing faith in the economy and business confidence has plummeted since the Budget in October.

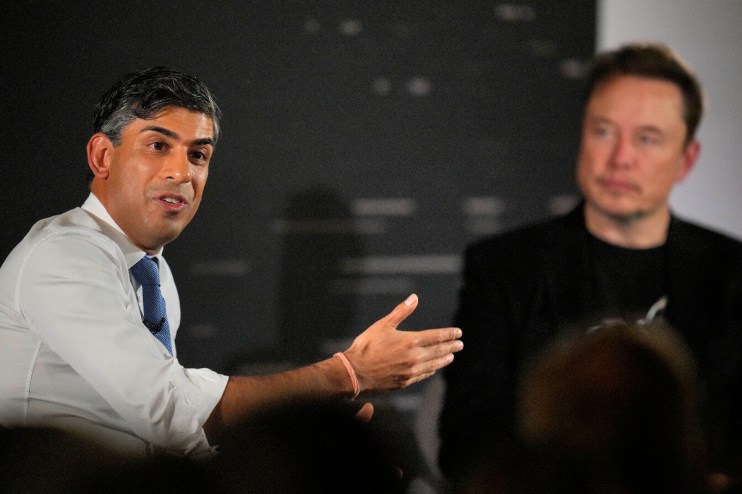

Amid the bleakness, some eyes have turned to the attention-seeking, billionaire Tesla CEO across the water. Elon Musk has been named co-chair of Donald Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency (which does not yet exist and will not be a department of the federal government) and is promising enormous efficiency savings and a “businesslike” approach to government. Obviously impressed, Ben Francis, founder of sportswear brand Gymshark, told The Daily Telegraph that the Prime Minister should follow America’s example, “bringing in competent business people to support the government in their policies”. He added that he had “quite a long list” of ideas to make the UK a better place to start and run a business.

Only one Prime Minister and one US president have held MBAs: Rishi Sunak and George W Bush. Are they selling the idea?

The idea that successful business leaders and entrepreneurs have the ability to transform the way government works, and to deliver unparalleled “efficiency”, is not a remotely new one. In 1915, David Lloyd George, then minister of munitions but 18 months away from the premiership, appointed Eric Geddes, general manager of the North Eastern Railway, to oversee the manufacturing and supply of weapons and ammunition.

The next year, Geddes was appointed inspector-general of transportation for the British Army in France, then, in 1917, he was put in charge of the Admiralty and found a seat in the House of Commons. He went on to be the first minister of transport (1919-21). Geddes brought hard-headed sense and reality to Whitehall, but he hated politics, gave up ministerial office and stepped down as an MP after less than five years.

A skills Venn diagram

The truth is that success in business and political ability rely on some of the same skills but also diverge, at best forming a Venn diagram. A CEO can issue instructions and rely on them being executed; a minister must persuade and cajole, attending to half a dozen different interest groups. Whitehall must be transparent and accountable; much of what government does is achieved by changing behaviour, not by diktat; and ministers ultimately cannot afford to fail in the same way that entrepreneurs can.

Geddes was a success, and other ‘imports’ from the private sector have achieved a great deal: retail executive Lord Woolton was a brilliant minister of food from 1940 to 1943 and then did important work as minister of reconstruction (1943-45); Lord Young of Graffham won Margaret Thatcher’s trust as an effective employment secretary and trade and industry secretary in the mid- to late 1980s.

On the other hand, the former director-general of the CBI, John Davies, was a disaster as Edward Heath’s trade and industry secretary (1970-72), bad at politics as well as unable to forge a coherent and successful industrial policy. Equally, Arthur Cockfield, former managing director of Boots, was ennobled and eventually made trade secretary in 1982 but had little impact, his intellectual firepower wasted by his inability to persuade colleagues.

Business wants a sympathetic hearing in Whitehall and energetic, imaginative ministers like Michael Heseltine, Nigel Lawson and Peter Mandelson: people who ‘get’ it. It does not want the task of governing subcontracted to it. Running the country requires a different set of skills to running a successful private enterprise. What is desperately needed is an effective mechanism for minds to meet and messages to be heard by both sides.

To understand how difficult it is to cross from business to government successfully, you might consider the fact that only one Prime Minister and one US president have held MBAs: Rishi Sunak and George W Bush. Are they selling the idea?

Eliot Wilson is a writer and strategic adviser