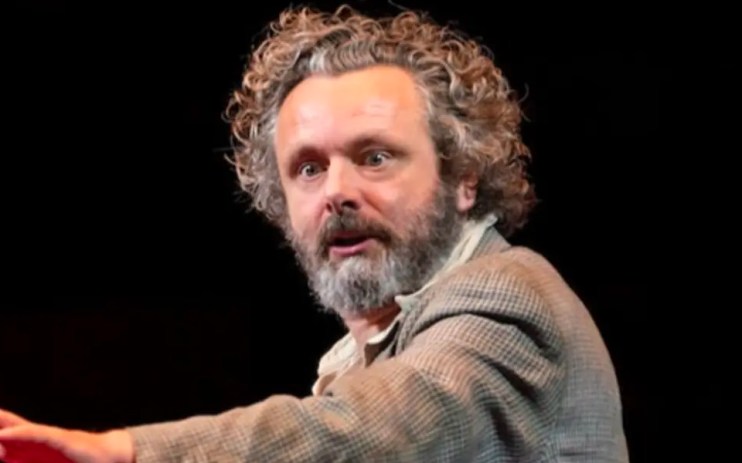

Under Milk Wood: Michael Sheen shines at the National Theatre

There are few opening lines as transportive as that in Dylan Thomas’ 1954 radio play Under Milk Wood.

“It is Spring, moonless night in the small town, starless and bible-black, the cobblestreets silent and the hunched, courters’-and- rabbits’ wood limping invisible down to the sloeblack, slow, black, crowblack, fishingboat-bobbing sea.”

It’s a surprise, then, when this is not among the first lines in this new version at the National Theatre. Rather than dive straight into Thomas’ epic poem about the minutiae of life in a Welsh seaside town, we open with a new framing device written by Siân Owen. A confused old man wanders across a nearly-bare stage until he is ushered back to bed by employees of his care home for the elderly. In the minutes that follow, dust jackets are pulled from the few props on the stage, a reference, perhaps, to the National Theatre itself finally pulling off its dust jackets and welcoming its first guests of the year.

The old man is Richard Jenkins, one of the characters from Thomas’ play, now old and befuddled, his memories all “muddled up”. His son Owain, a ragged, prickly academic played brilliantly by Michael Sheen, bustles into the home demanding to discuss some matter of family importance, only to find his father doesn’t recognise him. The words from the original play are Owain’s increasingly spirited attempt to rekindle the old man’s sense of self.

The device works well, providing a grounding-point before the free flowing, impressionistic poetry begins. Sheen is one of the finest actors on stage today and when he finally reads those lines – worth repeating: “the sloeblack, slow, black, crowblack, fishingboat-bobbing sea” – it sends a shiver down your spine. The characters who live in the fictional Llareggub – “bugger all” backwards – are made up of the residents from the home: a man with one eye becomes Captain Cat, the blind sea captain who dreams of his drowned shipmates; a lascivious old man becomes the baker with two wives.

Starting in the dead of night, we’re guided through 24 hours in this town, diving in and out of the inhabitant’s dreams, lusts and internal monologues. Set in the round, dinner tables and bars and boats are wheeled on by the ensemble cast, each vignette segueing into the next, with Sheen’s rhythmic delivery binding it all together.

Thomas had a wicked sense of humour and it’s brought to the fore here, especially Mr Pugh’s murderous intent towards his wife, and the town’s love of an evening bevvy (inspired by Thomas’ own love of a drink; he once left the manuscript for Under Milk Wood in the pub after a heavy sesh).

There are also wonderful, quiet moments, such as Polly Garter, the object of the village’s desire, secretly pining for her dead lover. When I sensed the sun finally disappearing over the horizon (the lighting is excellent throughout) it was with a genuine sense of sadness.

Much has been written about the warping of our collective sense of time over the last 15 months: how days dragged and months disappeared, and Under Milk Wood explores that melancholy passing of time as well as any play I can recall. It’s also steeped in nostalgia – the day described could be any day in Llareggub, whose rhythms flow as predictably and inevitably as the tide – and right now we could all do with a reminder of the before-times, when London theatre was in full swing.