Ukraine crisis highlights Europe’s dependency on Russian gas

Russia is currently facing the ire of the world following its illegal invasion of Ukraine, which is bringing misery to millions.

It is also the second largest producer of natural gas in the world. It serves European consumers of energy through a number of pipelines.

Proximity and the ease of transport means supplies from the country account for around a third of all gas imported to the continent.

There have been some marked swings in gas prices due to the Ukraine conflict. The West, however, has seemed careful up until now to carve energy supplies out of sanctions, and existing gas pipelines from Russia remain operational, it appears, at the present time.

The US is the world’s largest producer of natural gas. Supplying it to Europe over long distances, however, makes delivery an involved process. It first needs to be liquefied before being shipped across the Atlantic when “regasification” can occur at European liquified natural gas (LNG) terminals.

More pronounced spike in gas price inflation

It’s a similar situation for potential natural gas imports from the Middle East. German ministers are fast tracking the construction of two new LNG terminals, and there are proposals to delay the phase-out of conventional energy sources in the country, such as coal and nuclear.

But there may be limits as to what can be achieved in the near term.

Azad Zangana, senior European economist, says: “The German government is trying to reduce the impact of higher oil and gas prices from Russia and wean itself off Russian energy a little bit more.

“As renewables got going, natural gas was always seen as a cleaner alternative among the fossil fuels, but clearly the option of imports from Russia is less powerful now.”

Europe had been facing shortages of natural gas before the tragic events in Ukraine unfolded. A number of factors played their part, including a lack of investment in new gas projects and growing global demand.

“Spot” gas prices – the prices at which a commodity can be bought and sold for immediate delivery – climbed very sharply in 2021, reflecting tightness in the market.

Higher prices fed through into higher “headline” rates of consumer inflation, already elevated due to other pandemic-related factors. Headline inflation includes the more volatile cost of living components such as food, and energy.

Consumer inflation is widely tracked by consumer price indices (CPI), and headline CPI has already hit mid single digits in the UK and Europe, the highest for decades. It is expected to keep rising.

In spite of efforts by policymakers to manage the impact of energy price inflation on the end consumer, and business, options in the near term may be limited.

The UK government’s price cap limits the maximum amount suppliers can charge for each unit of gas and electricity, for instance. It only delays price rises however. Energy prices are set to rise materially on 1 April when the cap next increases.

The new cap means that a typical domestic energy bill will rise by about £700 a year, to around £2,000.

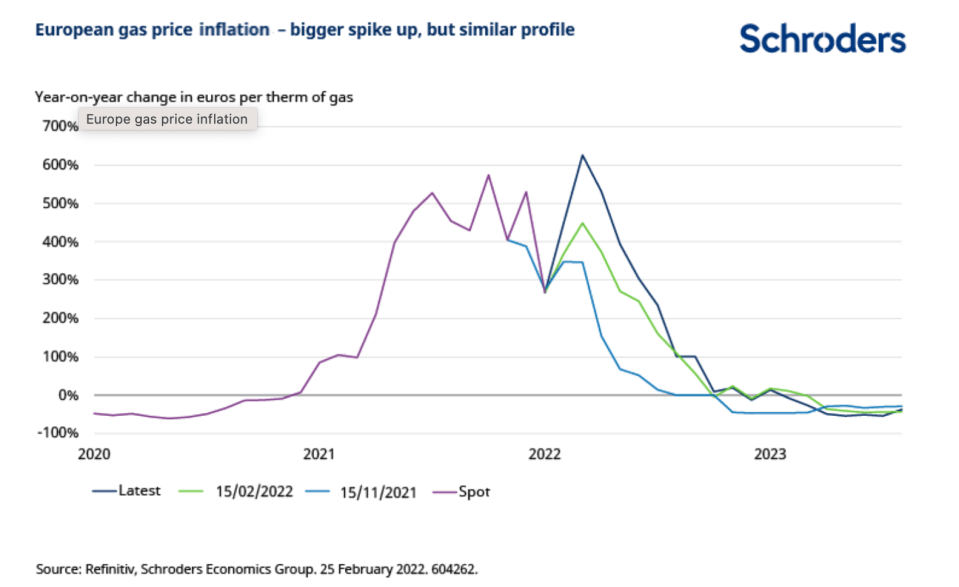

The chart above shows the expected path of European gas price inflation implied by “futures” markets. Futures are tradable agreements to buy and sell a set amount of commodities at set prices at set dates in the future.

This year’s expected spike in gas price inflation has become more pronounced since the Ukraine invasion.

Discover more by visiting Schroders’ insights or click the links below:

– Follow: Live blog: what does Russia’s invasion of Ukraine mean for markets

– Listen: Russian sanctions and what might happen if Russia turns off the taps

– Watch: Why now’s not the time to be making big bets

How to fill a “power generation gap”

“Over the last six years, Europe has attempted to reduce its dependency on Russian gas by significantly increasing its LNG import regasification capacity,” says Mark Lacey, Head of Global Resource Equities.

“As much as Europe is reliant on natural gas from Russia, it is now very reliant on imported LNG volumes to meet its energy needs.”

There are, however, limited LNG supplies to go around at the present time.

In recent years developed countries have turned to gas for electricity generation as they’ve scaled back coal-fired power stations. They’ve done this by utilising spare capacity at gas-fired power stations.

“Even though we expect the wind power market to grow by at least 150% over the next decade and the solar market by at least 200%, this does not imply that demand for gas falls over the same period”, says Lacey.

“Given the need to shut down a considerable amount of coal production, natural gas demand is likely to increase at around 4% per annum over the next decade to help fill the power generation gap.”

Events in Ukraine have exacerbated these existing pressures.

Pandemic created low base for energy inflation

Economists, however, remind us that current rates of energy price inflation need to be seen in the context of very low energy prices in 2020/early 2021 as a result of the pandemic.

Weak energy prices during the pandemic have created a low base for year-on-year comparisons of price levels. This has resulted in high rates of energy inflation due to so called “base effects”.

These effects are expected to fade – see the first chart again, and note its profile.

“We have a bigger spike up in the very near term but we still have a similar profile going forward,” says Zangana, commenting after the initial increase in energy prices following the invasion.

“Base effects start to kick in so by the end of this year the extra gas inflation will have eased off and by 2023 it will be a drag again on the headline inflation numbers.”

Topics:

Important Information: This communication is marketing material. The views and opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) on this page, and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other Schroders communications, strategies or funds. This material is intended to be for information purposes only and is not intended as promotional material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. It is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this document when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of an investment can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed. All investments involve risks including the risk of possible loss of principal. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Some information quoted was obtained from external sources we consider to be reliable. No responsibility can be accepted for errors of fact obtained from third parties, and this data may change with market conditions. This does not exclude any duty or liability that Schroders has to its customers under any regulatory system. Regions/ sectors shown for illustrative purposes only and should not be viewed as a recommendation to buy/sell. The opinions in this material include some forecasted views. We believe we are basing our expectations and beliefs on reasonable assumptions within the bounds of what we currently know. However, there is no guarantee than any forecasts or opinions will be realised. These views and opinions may change. To the extent that you are in North America, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management North America Inc., an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Schroders plc and SEC registered adviser providing asset management products and services to clients in the US and Canada. For all other users, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.