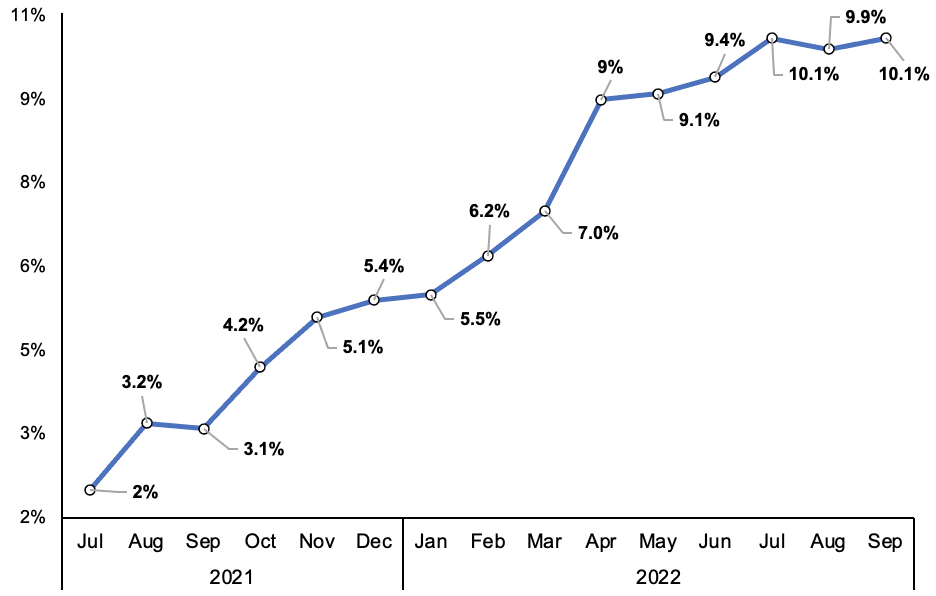

Bank of England to launch record rate rise to step up fight against 40-year high inflation

The Bank of England will have to hike interest rates by a record whole percentage point at its meeting on 3 November, City economists are betting today after inflation returned to a 40 year high of 10.1 per cent last month.

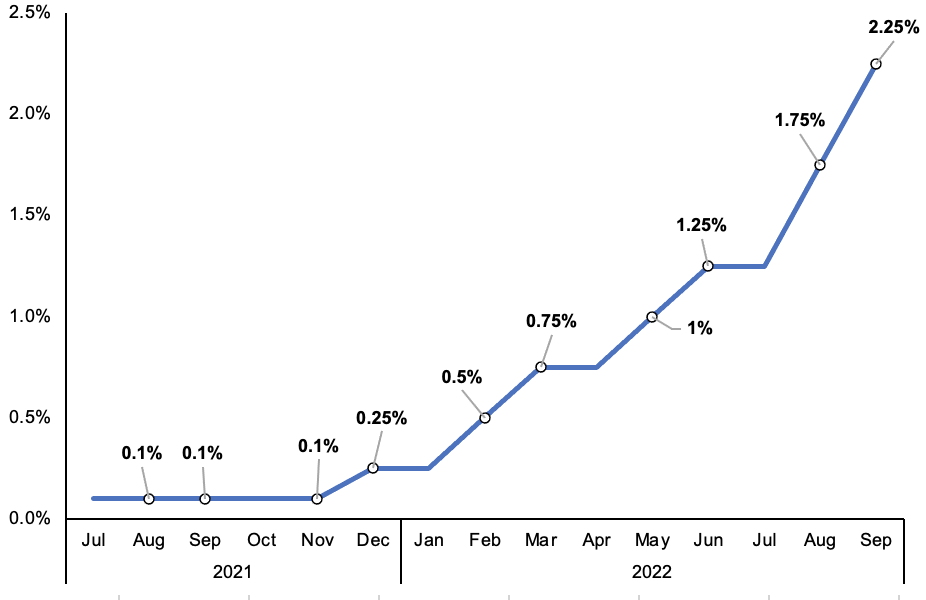

Prices are still rising sharply despite the Bank already lifting borrowing costs seven times in a row, strengthening the case for the central bank to step up the pace of rate rises.

The Office for National Statistics said today food prices have accelerated at the fastest pace in four decades, forcing the headline inflation rate above the City’s expectation of 10 per cent, but was in line with the Bank’s August forecast. It was also up from August’s 9.9 per cent reading.

The pound weakened around 0.5 per cent against the US dollar on the news, while the FTSE 100 dropped 0.49 per cent.

Gilt yields nudged higher. Rates on 10-year gilt kicked four basis points higher, while yields on the 30-year gilt, which has been highly volatile over the last month, fell 14 basis points.

Yields and prices move inversely.

Annual UK CPI inflation

Today’s release also suggested rising living costs are switching from being driven by international factors – such as high energy prices as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – to domestic price prices.

Service prices climbed sharply, while core inflation, seen as a more accurate measure of underlying price pressures, climbed to a 30-year high 6.5 per cent.

“The further strengthening in domestic price pressures despite the clear weakening in the economic outlook” means the Bank will have to launch a jumbo 100 basis point rate rise next month, Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics, said.

That would be the largest rate increase since the Bank was made independent 25 years ago, underscoring how the last year’s inflation surge has engineered a historic shift in UK monetary policy.

Inflation is now more than five times the Bank’s two per cent target.

“September’s consumer prices figures maintain the pressure on the [monetary policy committee] to hike Bank Rate substantially at its next meeting on 3 November, despite the developing recession,” Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said.

Governor Andrew Bailey said over the weekend the MPC’s expectations for the size of the rate rise have jolted upward after the government’s botched mini-budget.

Some economists were betting the MPC could back a 125 basis point rise to tame market turmoil and stronger inflationary pressures caused by prime minister Liz Truss’s tax cut plans.

Truss has since been forced to defer economic policy to new chancellor Jeremy Hunt and U-turn on nearly all the £45bn worth of unfunded tax cuts in the mini-budget.

September’s inflation reading is used to decide whether the government upgrades pensions in line with prices, earnings or 2.5 per cent under its triple-lock policy.

Speculation has mounted recently over whether Truss will also ditch this 2019 election manifesto pledge, but today, at PMQs, she said pensions will rise in line with inflation.

She has yet to commit to a similar move on benefits.

UK interest rates have climbed sharply this year

Hunt also cut short the £2,500 typical energy bill freeze to six months from two years, which could result in households being suddenly hit by a huge inflation rate in April.

The chancellor said the government has “acted decisively to protect households and businesses from significant rises in their energy bills this winter”.

But, Tombs said “if households start to pay the market price for energy again,” then inflation would climb to 11 per cent.

Governor Bailey and co late last night confirmed they will begin selling long-dated government bonds on 1 November in a bid to tighten UK financial conditions further to tame inflation.

The Bank had been forced to delay the start of bond sales, or quantitative tightening, from the beginning of this month to fight off market chaos triggered by Truss’s disastrous mini-budget.

The central bank created a £65bn temporary bond buying scheme to put a lid on surging yields on long-dated government debt. Rising yields sparked fears segments of the pensions industry would collapse due to creditors demanding they stump up cash to cover losses caused by tumbling bond prices.

Markets responded fairly well to that programme ending on Monday, with yields stable. The Bank used nowhere near the full £65bn allocated under the scheme.