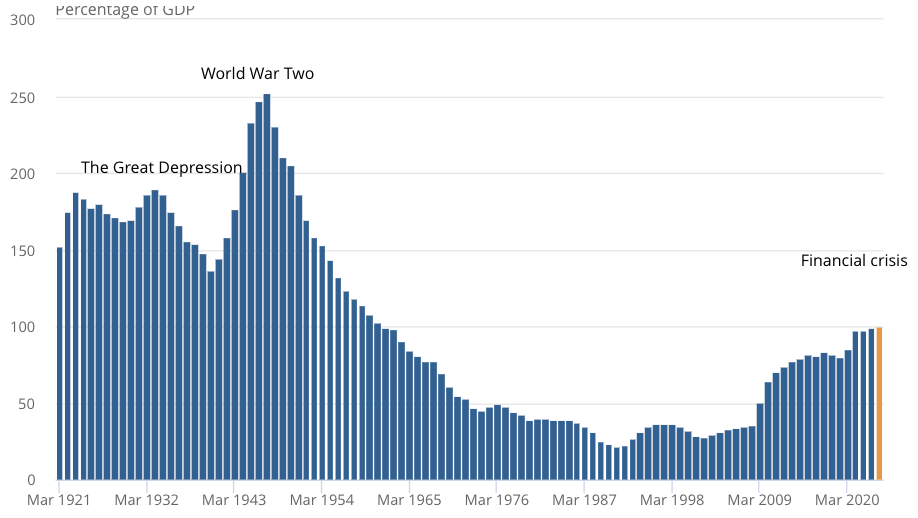

UK debt pile tops size of entire economy for first time since 1960s

Britain’s debt stock has swelled to larger than the size of its economy for the first time since March 1961, pushed higher by the government helping families with their energy bills, new numbers out today show.

The UK’s over £2.5 trillion debt pile represents 100.1 per cent of the value of its gross domestic product, according to official figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

The debt-to-GDP ratio – a measure of the strength of a country’s public balance sheet – has been pushed higher by a series of shocks that have prompted the government to raise spending to marshal the economy.

Banking turmoil during the 2008 global financial crisis, Brexit, the Covid-19 pandemic and the energy price shock after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have raised government borrowing.

Pandemic help including the furlough scheme, vaccine programme and household income support measures all lifted government spending at a time the economy was struggling.

ONS experts calculated that May’s £20bn borrowing total was the second highest record for that month since data started. It was slightly below the City’s expectations.

UK’s debt-to-GDP ratio has been rising quickly since 2008

Last month’s debt increase means Chancellor Jeremy Hunt is on course to top the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) borrowing forecast. Borrowing has reached £42.9bn so far this financial year, £2.1bn higher than the OBR’s projections.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt said: “It would be manifestly unfair to leave future generations with a tab they cannot repay. That’s why we have taken difficult but necessary decisions to balance the books in order to halve inflation this year, grow the economy and reduce debt.”

At the March budget, the OBR judged Hunt to have the slimmest headroom against his fiscal targets of any Chancellor since the organisation was created in 2010.

However, the ONS often revises its public finances estimates. Stronger than expected economic growth would also aid the public finances.

When the amount of cash a government collects in taxes falls short of its spending, it runs a budget deficit. It plugs the gap by borrowing money from investors.

Since last autumn, the government has capped typical annual household energy bills at £2,500. The Treasury has been paying the difference between what gas and electricity have to pay to source energy on wholesale and what they can charge customers.

That support package will end this summer. Rising benefit payments have also pushed up borrowing.

Britain’s sluggish economic performance since the 2008 financial crisis has knocked tax revenues, while an ageing and growingly sicker population has raised health spending, putting upward pressure on the deficit.

Rapidly rising prices have also boosted the amount of money the government has to repay investors who have hoovered up UK debt. A large chunk of the country’s debt stock is tied to the retail price index, an old measure of inflation, which has surged over the last year and a half.

Britain’s interest bill came in at £7.7bn last month, lower than May 2022’s £7.9bn figure.

Separate ONS numbers out this morning showed inflation held steady at 8.7 per cent in May, beating the City’s forecast of a drop to 8.4 per cent.

While inflation is still tipped to fall over the next 12 months, it is on track to outstrip the OBR’s calculations, eroding the Chancellor’s room for tax cuts.

“The sharp deterioration in the outlook for debt interest payments over the last month suggests that the Chancellor will not have scope to cut taxes before the next general election, which must be held by January 2025,” Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at consultancy Pantheon Macroeconomics, said.

“Indeed, we estimate that the OBR would revise up its forecast for debt interest payments by about £39bn in 2024/25, and about £17bn in five years’ time,” he added.