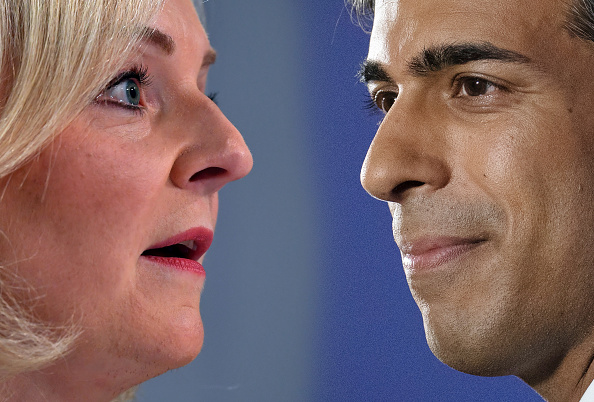

Truss and Sunak have gone astray as they fight for Thatcher’s legacy

Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak will be glad the hottest day of the heatwave is over, because for the Conservative party it will be a long summer of heavy slog. As the final two candidates battle it out to claim the leadership they will criss-cross the UK for hustings in front of party members before the next leader—and the next prime minister—is announced on 5 September.

It is 30 years since James Carville coined the phrase “it’s the economy, stupid” to remind candidates for any political office what really drives voters. It remains as true today: while the early campaign was distracted by issues such as gender identity and schooling, Tory members, like the wider electorate, are focused on the cost of living, energy prices, inflation and tax bills. Neither Sunak nor Truss should need the Ragin’ Cajun to remind them what will swing the result: the weight of what’s in their pocket.

The economic policies proposed by the two candidates so far are a strange exercise in “same, same but different”. They are currently being distinguished by approaches to taxation: Sunak, who was in charge of the Treasury until a few weeks ago, has (perhaps by necessity) pledged a safety-first stance, arguing against immediate tax cuts for fear of stoking inflation; Truss, meanwhile, wants to “supercharge” the economy and has vowed to reverse the National Insurance increase, abandon plans to raise corporation tax and suspend green levies on energy bills.

This presents a stark choice for the party. Sunak is the prudent, cautious candidate who will reassure the country that its current pain will lead to gain if it stays the course, while Truss talks of overturning two decades of economic orthodoxy (for 12 years of which, one might note, the Conservative Party has been in office). She threatens to make a reality of the radicalism in Britannia Unchained, a right-wing portmanteau published in 2012.

Given this divergence, it is interesting that both candidates are seeking to appropriate the mantle of Thatcherism. Sunak sees himself as the “heir to Thatcher”, while Truss has been auditioning for her role in the revival performance for some years, sounding hawkish on foreign policy, sitting atop a tank and cosplaying the Iron Lady at every opportunity.

They cannot both be right. Or can they? One of the problems of this leadership contest, and indeed of Conservative politics more widely for the last 30 years, is that Thatcherism is a fondly remembered fever dream for many modern Tories. After all, anyone now under 40 will have no real memory of the Thatcher years as they happened. Instead, they select a compilation of her greatest hits and skip over the tracks which neither interest nor suit them.

Thatcherism (itself a misnomer, as the intellectual heavy lifting was done by others) was never as simple as cutting taxes, or keeping inflation low. In part, yes, it was a response to the specific economic circumstances in which the UK found itself in the mid- to late 1970s, but it was a clearer and loftier mission than that. Nigel Lawson, chancellor from 1983 to 1989, listed its economic characteristics as “free markets, financial discipline, firm control over public expenditure, tax cuts”, but these were means to an end.

The real ideology of Conservatism—or at least a section of it—is predicated on the moral good of personal freedom. Low taxation is to be promoted because it leaves people in control of more of their money, of which they are the best guardians. A small state allows personal autonomy and promotes communal and voluntary solutions to societal problems.

At this stage, we are in a rather crude battle of immediate levels of tax. Sunak and Truss are trading headlines, which in a world with a short attention span is understandable, but neither has yet to commit to any real radicalism. Truss has admitted she is open to the possibility of reviewing the Bank of England’s mandate, but there is little else to suggest that the shape of the British economy will be altered substantially.

There are six weeks of campaigning to come. Business will be watching carefully for signs, even hints, of a deeper economic philosophy from either candidate. If, as early polling suggests, Liz Truss becomes prime minister, we will see a reduction in some taxation offset by greater borrowing, which is then paid off more slowly. But fundamental questions remain: how can the age-old problem of low productivity be solved? What kind of economy does the UK want and need? Where are our new trading partners? For answers to those, we may have to wait a little longer.