Tokyo 2020 six months to go: How Japan is looking to Olympic and Paralympic Games as a catalyst for modernisation and regeneration

The contorted face of the godfather of sumo wrestling, Nomino Sukune, glowers from a mosaic at Tokyo’s New National Stadium.

A few metres to the right, a Greek goddess with a laurel wreath is depicted in a similar monochrome mural.

Both artworks were salvaged from the previous national stadium, centrepiece of the 1964 Olympics, and have been repurposed for the striking £1.2bn arena which now stands in its place and where the city will begin hosting its second summer Games in six months’ time.

Together they mark one of the entrances to the venue, but they are also emblematic of a central theme of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games: sustainability and environmental consciousness.

“Be better, together – for the planet and the people” is the organising committee’s slogan, and there have been some meaningful and eye-catching initiatives to back up the eco-friendly talk.

The gold, silver and bronze medals draped around athletes’ necks later this year have been manufactured using metals extracted from old mobile phones and other electronic devices following a nationwide appeal for donations from the public.

Podiums are being made from recycled plastic and the beds that competitors will sleep on in the athletes’ village have been fashioned out of cardboard, which will itself be reused in paper products after the Games

The torches that will carry the Olympic flame on its relay around the country’s 47 prefectures, meanwhile, contain aluminium from prefabricated houses damaged in the devastating earthquake of 2011.

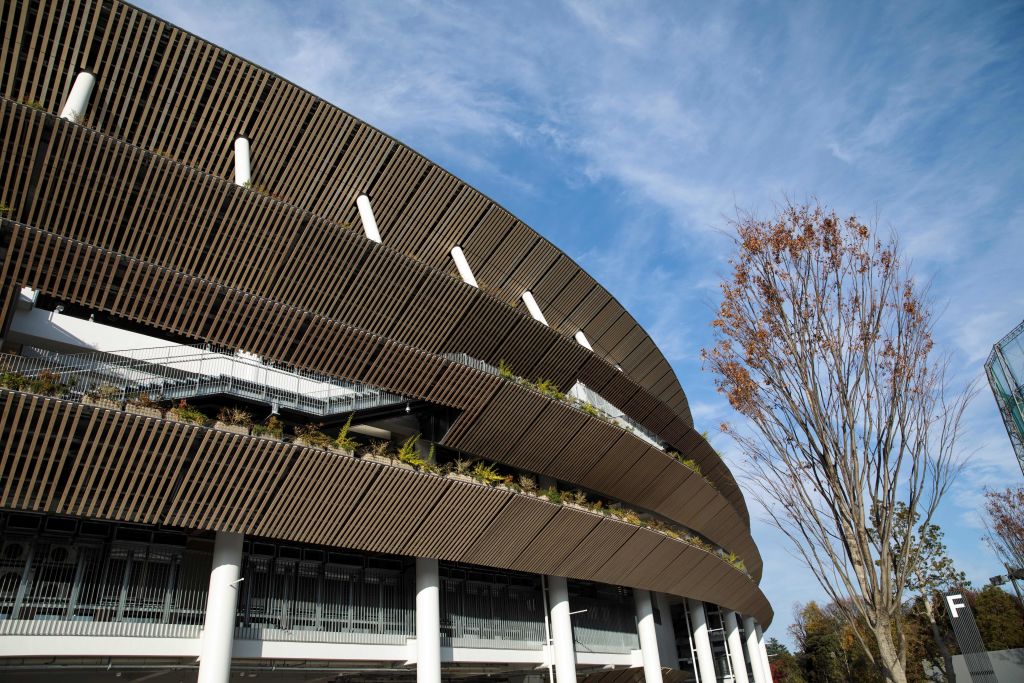

Natural motifs also abound in the Kengo Kuma-designed New National Stadium.

Kuma’s trademark emphasis on wood – a nod to traditional Japanese styles – is present in decorative tiers of eaves that encircle the bowl like a planet’s rings.

The fifth-floor exterior walkway is fringed with grass and 670 plants designed to bloom year round and create a “grove in the sky”.

It will be open to the public as a sort of urban garden even when the stadium is not in use.

Inside the 60,000-capacity venue, meanwhile, the seats are coloured green, brown and neutral tones.

The ‘reconstruction Games’

Unusually for a host city, Tokyo is reusing several legacy venues from its first stint as Olympic host 56 years ago, including the Metropolitan Gymnasium, which will stage table tennis, and Yoyogi National Stadium, which will house handball.

Other existing sites are also being co-opted, such as the Nippon Budokan and Kokugikan Arena, the spiritual homes of martial arts and sumo respectively, Ariake Tennis Park and the Tokyo International Forum exhibition centre.

Not only does reusing venues play into the sustainability theme, it is also a way of mitigating the cost of staging the Games at a time when would-be hosts are increasingly thinking twice – or teaming up in joint bids – before signing up to put on such vast major sporting events.

Another of Tokyo 2020’s self-appointed aliases is “the reconstruction Games”, a reference to repairing the damage wrought by the 2011 earthquake and subsequent tsunami, which killed tens of thousands and caused meltdowns at a nuclear power plant in Fukushima.

To that end, Fukushima and Miyagi, two of the worst-hit prefectures, will stage some of the baseball and football matches, respectively. As well as receiving some reflected Tokyo 2020 glow, it is hoped this will stimulate economic activity in the areas.

Fukushima – specifically J Village, the national football training centre that served as operation base for relief efforts for eight years – has also been designated the starting point of the torch relay, which sets off on 26 March.

Green credentials?

Not everyone is convinced of Tokyo 2020’s green credentials, and in recent weeks organisers have been accused of falling well short of the sustainability vision laid out.

Last month 12 NGOs joined forces to argue that construction of the New National Stadium had caused a “severe negative impact on the tropical rainforests in Indonesia and Malaysia”, adding that their attempts to raise concerns had been effectively ignored.

This week the World Wildlife Fund weighed in, saying procurement protocols for the Games “fell far below globally accepted sustainability standards”.

Tokyo 2020 chiefs have rejected the criticisms, saying its protocols met standards set by other NGOs such as the Forest Stewardship Council and the Marine Stewardship Council.

Olympic and Paralympic Games also represent a test of a population’s enthusiasm for such events.

Anecdotally, reaction from a handful of Japanese residents in Tokyo and Kumamoto who spoke to City A.M. was mixed, with anticipation lukewarm and suggestions that the vast outlay might be better spent elsewhere, for instance on repairing damage caused by October’s typhoon Hagibis.

Apathy or negativity among hosts before the Games is common, however, owing to the tendency for negative news stories about preparations to gain greater traction – see London 2012 and Rio 2016 – and typically fades once the excitement of the occasion begins.

Last year’s Rugby World Cup in Japan was a huge success, meanwhile, highlighted the country’s reputation as welcoming and generous hosts and perhaps offers the most reliable indicator that stadiums are likely to be full and the organisation seamless.

If so, industry experts predict that Tokyo will join the likes of London in the top echelon of sporting host cities.

Hot ticket

For a country synonymous with technological innovation – naturally, it has a robot project that promises R2D2-like units ferrying items around venues – there is a sense that Japan is looking to Tokyo 2020 as a catalyst for modernisation in other areas.

Aside from the focus on sustainability and regeneration, the Games have spawned other initiatives aimed at improving access for those with disabilities and introducing more flexible working.

Logistically, operations appear in line with with Japan’s reputation for organisation.

All but one venue has been completed, more than 3.8m tickets have already been sold while a budget that at one stage threatened to spiral has been stabilised at £9.5bn.

Properties in the athletes’ village, which is to be converted into one, two and three-bedroom apartments after the Games, have been a hot ticket.

The 5,000 dwellings already sold were 70 times oversubscribed, even at an average price of £690,000 each.

If all of that is anything to go by – and though debate may continue over its green credentials – Tokyo 2020 should prove a success.