Together in electric dreams: The poetic beauty of pylons

“The closer you look at beauty,” writes the novelist Alan Hollinghurst, “the more unsettling it becomes.”

This line from the novel The Line of Beauty, in which the glamorous protagonist Nick Guest propels himself through life in the reckless pursuit of aesthetic pleasures, drifted through my head as I stood in a damp field on the outskirts of Oxfordshire. Sodden and skulking, ankle deep in mud, I gazed up in both awe and disgust at the telos of my trip: the Sandford Lock electricity pylon.

It was a tiresome journey: through pelting rain I had travelled eight miles across London, boarded the fast train via Reading to the centre of Oxford, cycled up to the Folly Bridge, where I left the city and skirted south beside the Thames for a further five miles. I ended the journey cursing the man who had inspired this mad mission – hours of cycling through torrential rain to see a transmission tower.

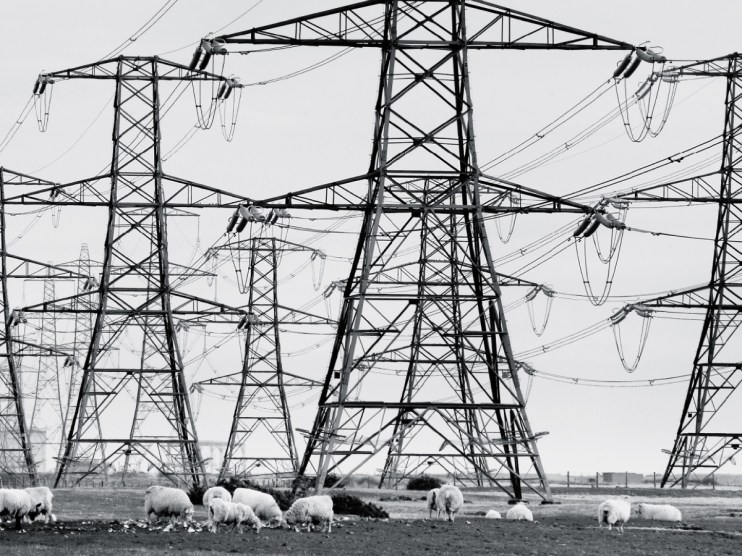

That would be Kevin Mosedale, a physics teacher who runs the Pylon of the Month website, who had told me this is the best pylon in the UK to visit. “You can get up close and personal with it,” he explained. I was sold. But standing at the feet of this metal giant I found myself conflicted. Dizzyingly latticed and layered, its criss-cross structure rises frenetically towards the sky in a way that makes your head spin. It’s only when you step back that it takes on its ethereal, stoic beauty. Up close, 20 tonnes of steel is cold and abrasive.

•••

Before Pylon of the Month was even a twinkle in Mosedale’s eye, there was the Pylon Appreciation Society. This online group was formed to help mega fans, whatever their age, with any pylon-related questions. “Will the Society’s badge be sufficient to show to the police if I’m stopped for taking photos of pylons? I am worried that people might think I am a terrorist,” asked one member on the group’s messageboard.

Sadly, the founder of the Pylon Appreciation Society, a woman named Flash Bristow, passed away in 2020 and the society is now dormant. No longer can you pay £15 to sign up for a welcome pack that includes a photo card, “parts of the pylon” print and a badge.

The website still exists, though, with a distinctly 2006 aesthetic and a charming welcome message: “It’s simple: the Pylon Appreciation Society is a club for people who appreciate electricity pylons. Enthusiasts range from primary school children to retired engineers and include anyone who is interested or inspired by transmission towers.”

Nowadays, pylon junkies have Mosedale’s site, which posts a different picture of a pylon each month (obviously) with an accompanying essay describing why this particular zinger was chosen. The bio of his X account reads “All pylon life is here”. It has almost 2,500 followers, many of whom interact regularly with him and suggest their own favourite pylons from countries across the world (each has a different design; when matched with foreign terrain, the ensuing scenes can be truly delightful).

To probe the aesthetics of a pylon is to ask ‘what is ugly?’ and question where our notions of beauty come from

Some might assume that anyone who ran a blog called Pylon of the Month was an aesthetic contrarian, someone resolutely determined to be different, but Mosedale is a softly spoken, mild-mannered physics teacher who isn’t looking for glory or fame (though he did once appear on Politics South East to talk about his site).

“When I was teaching electricity in 2008, there was a website called Pylon of the Month and we used to have a laugh about what kind of saddo would have a site like that,” Mosedale says. “When it stopped working a colleague said I should take it up, so I started doing it for a laugh and it grew from there. Whenever I started talking about it, people were curiously drawn to it. Like, is this guy for real?

“People want to know why on earth someone would have a website about pylons – they’re not necessarily interested in the pylons themselves.” And in fairness, he’s the first to admit that the bounce rate on his website is “very high”. He says his audience is mostly made up of English-speaking countries: “I haven’t cracked China or Russia,” he says, a little wistfully; China’s pylons are notoriously tall.

The design of pylons is Mosedale’s specific area of interest. They are “about as efficient as they can be,” he says admiringly. They are designed to do one job incredibly well, making them a triumph of form and function, an elegant, minimalist solution to a pressing engineering problem.

•••

Pause for a moment. Picture a pylon. How does it make you feel? If you’re anything like my followers on X, the answer will be, well, “bad”. Having naively assumed others would agree, I published a piece in City A.M. arguing that pylons are “skeletal beauties”.

“They are not ‘works of art’,” replied one user, “not to people who love nature and the countryside”. They pointed out my location on X was set to an inner-London suburb, which put me in that group of Yimby-minded urban elites who have never been threatened by the prospect of a metallic monster being built in their backyard, instead enjoying the luxury of constant and invisibly-supplied electricity.

People like me can take the train from Euston to Glasgow and marvel at the pretty pylons snaking their way across the landscape, a line of monoliths carrying their electric cargo beneath their arms. It makes sense that those who dislike pylons typically live nearer to them. Those who admire them – such as myself, Mosedale and Flash – live in cities.

There are 90,000 electricity pylons across Britain connecting 122 power stations to consumers using 4,000 miles of cables. Some stand as high as 50 metres and weigh around 20 tonnes. They carry up to 400,000 volts of electricity, which is a lot; as little as 100–250 volts is enough to kill you.

And there are set to be a whole load more: over the next seven years, four times as many will be built than in the past 30 years. That’s because a net zero Britain will need more electricity – to charge electric cars, for example – and will rely more on renewable energy like wind, which currently accounts for 30 percent of the UK’s total electricity generation and is set to grow, with 24 new wind farms to be switched on by 2030.

The UK’s first pylon was built in 1928 by the nascent National Grid. The ‘lattice’ design was intended to be delicate – at least more delicate than brutalist structures seen in Europe and the United States. That design has proved enduring; only recently has a new ‘T-shaped’ pylon started cropping up.

The very name ‘pylon’ (which means traffic cone across the pond) was chosen by National Grid architects as an allusion to the structures’ light-ferrying grandeur. In Ancient Egypt, a pylon was a gateway with two towers either side of it. The pylon represented two hills between which the sun would rise and set, and was where rituals to the Sun God would be carried out. The National Grid’s mission to bring power to the country was equally noble: after all, it has given us light, power and heat.

Despite their worthy heritage, however, pylons have powerful enemies, not least former home secretary Priti Patel, who suggested in parliament last autumn that Britain should “pull the plug” on them and “build an offshore grid”. She even created a low-budget video boasting of her anti-pylon stance, set to jingly music. She and 13 other Tory MPs have joined forces with campaigners from the Essex Suffolk Norfolk Pylons brigade, waging a cold war against the National Grid (when I spoke to someone from the National Grid, he was wary of discussing these pylon warriors, many of whom have an acute case of social media addiction).

•••

When I finally rang Rosie Pearson, I made a confession: “I like pylons,” I said bashfully. We agreed to disagree.

“I’m not directly affected by them,” she said, which surprised me given she founded the Essex Suffolk Norfolk Pylons group and started the petition rallying against the proposed 180km route of new pylons set to sweep across the South West.

“But the [proposed] line goes straight through the woods just 50 metres from my dad’s house. Woods he planted himself. When the proposition came in, I thought ‘Over my dead body!’ He’d planted that for nature. He’s too ill to fight but I’ve campaigned before. I don’t want to but I can,” she told me enthusiastically.

Then she laid out a series of “heart rendering personal stories,” which were indeed saddening: someone’s house that had become unsellable. Someone else whose house price had fallen 40 per cent. Someone with a pacemaker who was worried he would be unsafe in his own garden. Worse still, this power isn’t even intended for the people living in these areas – it’s all being directed to London.

The idea that someone could be affected by the National Grid’s construction and not receive compensation seemed wild to me – and indeed National Grid says the compensation scheme hasn’t been announced yet because the South West pylon scheme hasn’t been finalised (it’s still in the consultation stage).

There is this idea of pylons being paths to civilisation, stretching across big, empty landscapes. It’s a powerful artistic symbol

It should be noted that there are serious disadvantages to burying pylons or building them offshore. “You are effectively sterilising land use in the area,” is how Richard Smith of the National Grid described sinking – read “burying” – power lines. Currently a tiny proportion of Britain’s network is underground, almost exclusively in cities. It is up to 17 times more expensive than building al fresco cables, the lines need replacing more often and a wide berth (up to 40m) must be cleared with no building on top of it.

Pushing pylons offshore is even worse, according to Simon Cran-McGreehin, head of analysis at the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit. “At some point those lines have to come onshore to reach customers, otherwise it’s like a ring-road without any routes into town,” he says. If pylons out at sea break, it’s much harder to fix them than the ones you can amble up to on your way along an Oxfordshire cycle path. This is the argument that Mosedale, who is sympathetic to the pylon haters, made to me. Ultimately, it is a matter of economics.

Yet, aesthetically speaking, pylons provoke more ephemeral questions. What is ugly? Where do our notions of beauty come from? Who dictates which objects are deemed beautiful? We are told pylons, cooling towers, cranes and other objects of heavy industry are unsightly – blights on the landscape, scourges of mother nature. But part of this is social conditioning. Take the Eiffel Tower, which has a certain pylon-like elegance. It is now considered one of the most romantic structures on the planet, but it was lambasted when it was first erected, described by artist and wallpaper-maker William Morris as “a hellish piece of ugliness”.

I spoke to Zoe Dutton, a freelance artist in Glasgow, who has a tattoo of a pylon. Why does she like them so much? “They’re man-made things staked into the landscape. For me, celebrating that stuff is the opposite of Nimby-ism. If I want to boil the kettle and browse the web, I’ll need pylons, telephone poles and wires.

“There’s also this idea of them stretching across big empty landscapes, being these paths to civilisation. As an artistic symbol, it’s one of the first things to come out of my head when I go to draw something abstract. There’s also the crucifix imagery,” she adds, the bare metal arms of pylons bearing a resemblance to Jesus on the cross, arms open wide; ‘help me’, they seem to say.

All this talk of beauty and ugliness brings to mind an Oscar Wilde witticism (there’s always an Oscar Wilde witticism): “I have found that all ugly things are made by those who strive to make something beautiful, and that all beautiful things are made by those who strive to make something useful.” While I’m fairly sure Wilde would have hated the electricity pylon, his phrase still sums up these fiercely utilitarian structures, which, though quietly necessary, are ignored by everyone aside from the National Grid and a handful of poetic aesthetes. For me it’s the startling sight of raw, modernist function set against the green, yellow and brown of the Oxfordshire countryside, the dramatic coexistence of nature and industry, and probably – just a little bit – the contrarianism of it all.