Those who fear automation will be its only casualties

Whatever can be automated, should be. And regardless of whether it should, it will be. Automation has been a persistent economic force since the first industrial revolution, and an essential feature of any competitive business.

The use of machines and other forms of automation to boost productivity is a major factor behind the rapid global progression of the past 300 years. Johan Norberg, historian and author of Progress, links automation to such improvements as the doubling of life expectancy in the last hundred years, and the decrease of extreme poverty from 94 per cent in 1820 to 11 per cent today.

A study by Deloitte based on UK census data since 1871 found that machine technology had also had a positive impact on job growth, as well as transitioning the labour market away from physical labour.

Despite compelling predictions such as that by the Oxford Martin School that nearly half of all current jobs in the US labour market will become automated in the next 20 years, history has always demonstrated that job growth from new technology eventually exceeds the losses it creates. There is no reason to expect any different from this current wave of automation.

I work in digital advertising, an industry that has profited immensely from automation over the past decade. The trading of media inventory used to take place much more slowly, with negotiations between media agencies and publishers happening over the phone or during long lunches. The measurement of performance might take months. The introduction of the live auction enabled automated media buying; the use of digital advertising technology allowed us to measure audience response immediately.

Digital advertising has led the UK ad industry to consecutive annual growth for the past decade. Between 2004-2014, digital ad spend increased from £800m to £7.2bn, and is predicted to reach 50 per cent of overall ad spend by 2020 (based on a recent report by the IAB). There would have been far fewer jobs in advertising without the rise of automated media buying.

The rise of automation in advertising didn’t destroy jobs, it just changed the game, leading to a burst in roles that had never before existed. Computer scientists suddenly found themselves developing ad copy testing software, traditional marketers started writing code to interact with the algorithms controlling search ranking. PPC experts, SEO specialists, ad fraud prevention vendors, and thousands of other new jobs relating to the digital era of advertising emerged.

History has always demonstrated that job growth from new technology eventually exceeds the losses it creates.

Advertising is one industry among many, and each will have a unique relationship with automation. Still, what seems to be consistently overlooked, or simply not imagined, is the tendency for technological disruption to lead to the creation of new types of labour.

Many of the jobs performed by this generation would have been simply inconceivable to the generation that preceded it. Social media influencers, for example, or front-end developers. Thomas Frey, former IBM engineer and author of Communicating with the Future, provides a list of 162 jobs he foresees being created in the near future, based on the growth of new technologies such as IoT, VR, biotech, and 3D printing. A report by the World Economic Forum predicts that 65 per cent of children entering primary school today will ultimately end up working in completely new job types that don’t yet exist.

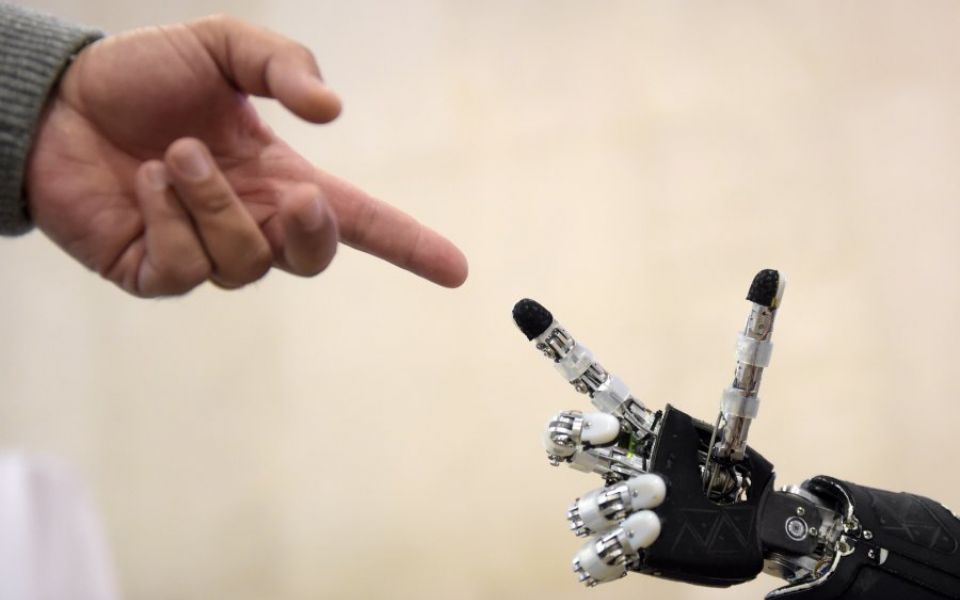

Automation can increase demand for, and create new types of, labour. It can also enhance existing jobs. My company (Brainlabs) was recently given some media attention for our decision to replace our receptionist with a robot, and inevitably there was some social media contempt directed our way for facilitating the rise of the machines.

In reality, the receptionist that was replaced remained an employee, just with more time to focus on the tasks that were exclusive to human intelligence. Until AI reaches AGI, automation will only be able to replace the aspects of human labour that frankly aren’t that interesting. Automation, at least for the foreseeable future, will normally facilitate a better quality of human work.

Whether via a robot receptionist or through automating reporting or any of the thousands of other applications within our business, automation has accelerated our growth. In five years, we have expanded from one to 150 staff, largely thanks to the enhanced productivity automation causes.

It’s partly a question of investing in technology. Imagine how inaccessible, slow and inefficient the world of investing would still be if it wasn’t for the digitisation of securities (formerly traded using paper certificates), for example. But more important is adapting the culture of a business to one that is willing to implement automation wherever possible: identifying opportunities, rather than anxiously resisting it.

In my industry, sophisticated uses of machine learning are being used for processing data, optimising targeting, adjusting bidding strategies.

Yet still, the bulk of the automation we have benefited from has been far more mundane: scripts to automate tasks on Excel, routine emails HR would otherwise have to manually type hundreds of times a week, repetitive processes the new business team use every day.

New technology just expands the scope of tasks that can be automated – the principle is always the same.

Automation does not represent the death of human labour, but it may lead to the decline of many businesses – that is, at least those that don’t fully embrace it.