The West faces copper crisis as China dominates key markets

As the West gathers in Egypt to establish new climate pledges, holding hands with allies and rivals to renew distant net zero commitments, the realities of a green future are being felt across commodity markets.

Countries are scrambling for essential minerals to power their green ambitions, and the vast growth in infrastructure required to transition developed economies to low carbon futures.

They are also clamouring to reduce their reliance on fossil fuels from unreliable overseas partners, such as Russia after its invasion of Ukraine.

One of the essential minerals in this shift is copper, which is vital for wiring renewable electricity systems, including batteries and photovoltaic cells in solar panels.

This makes it an essential mineral for electric cars, green energy projects and low carbon infrastructure.

Over the next two decades, the International Energy Agency expects it to be one of the three dominant minerals alongside graphite and nickel.

The Paris-based climate group forecasts demand for copper to nearly treble by 2040 for clean energy projects as countries shift to low-carbon energy generation to meet net zero goals.

The Paris-based climate group forecasts demand for copper to nearly treble by 2040 for clean energy projects as countries shift to green energy generation to meet net zero goals.

However, one of the leading experts in commodities markets has warned that the West has fallen behind China in the race to secure copper supplies, due to its short-sighted approach to commodities and energy policy.

Copper patience reaps dividends

Boris Mikanikrezai, metals analyst at commodity specialist Fastmarkets, told City A.M. that China’s dominant presence in emerging copper markets meant the West was in “more trouble” than its rivals when it came to obtaining essential minerals to meet its future needs.

In his view, China’s patient acquisitions of copper resources as a long-term investment placed them at an advantage to Western companies powered by investors entering and leaving the markets during boom-and-bust periods.

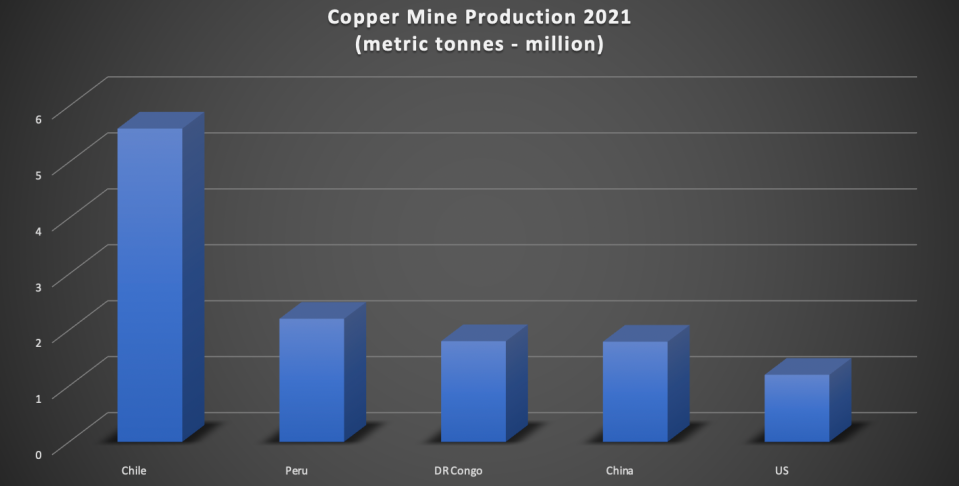

The commodities expert noted that mining was shifting from dominant players in South America such as Chile and Peru to new emerging markets, including African nations such as Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo) and Zambia.

He said: “If you look at how the Chinese deal with African mining, you can see the objective is to secure metals over the long-term. While, in the West there is more of a short-term view based on cycles. This is a problem for the West going forward.”

Mikanikrezai argued the lack of patience towards minerals could haunt the West, with too much focus on market performance over long-term patterns in consumption.

He said: “It’s not important whether copper is in deficit, it is whether you can access copper? If all the Chinese companies have control over the copper supply, what do you do?”

This gloomy sentiment contrasts with recent comments from BHP boss Mike Henry, who dismissed the idea that there could be supply shortages and potential crunches for Western countries.

“The world’s not going to run out of copper,” Henry told the Sunday Times. “We can be very confident about that.” he added.

“There’s more than enough units in the ground to meet the world’s need for those commodities.”

However, Henry admitted that if there were supply problems in the future, he said prices would need to rise enough to make it worth mining more obscure deposits.

China stays ahead of Western rivals

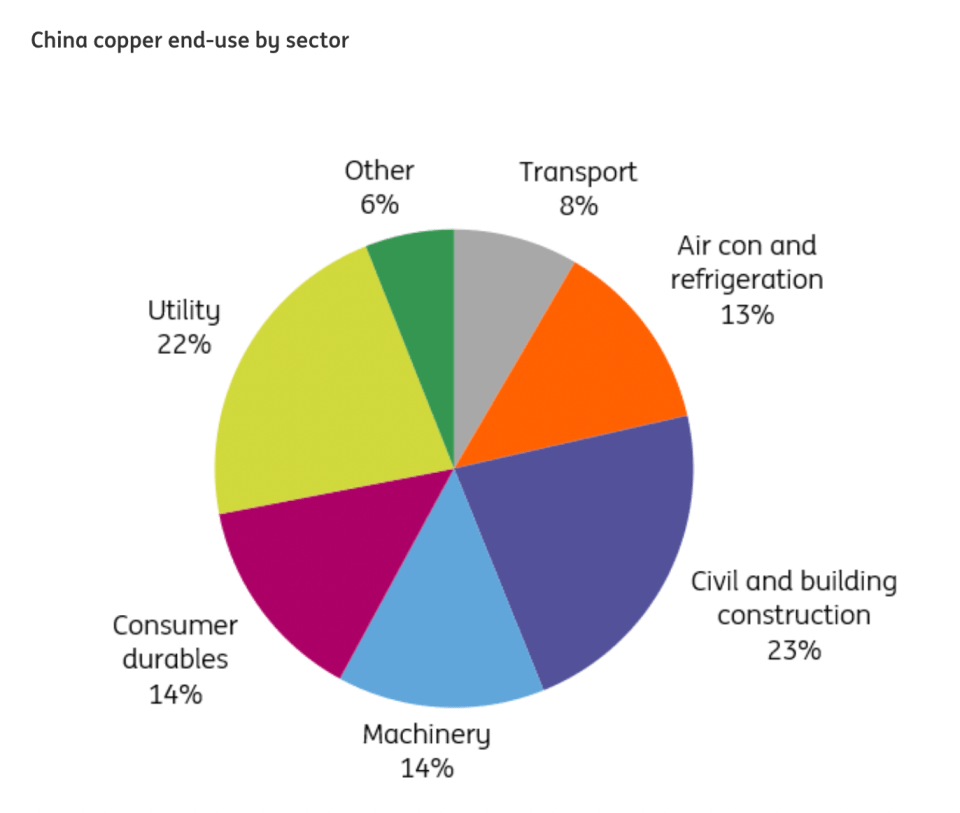

China has a dominant presence in DR Congo – which is also the world’s largest provider of cobalt, backed by lines of credit from state banks worth hundreds of billions of dollars. Big players such as CMOC control vast sites such as the Tenke Fungurume mine.

The West is pushing to develop its own minerals policies, with the UK launching a critical minerals strategy earlier this year to boost research and build alliances with like-minded nations.

Friendly producers of copper include US, Australia, Canada and Poland.

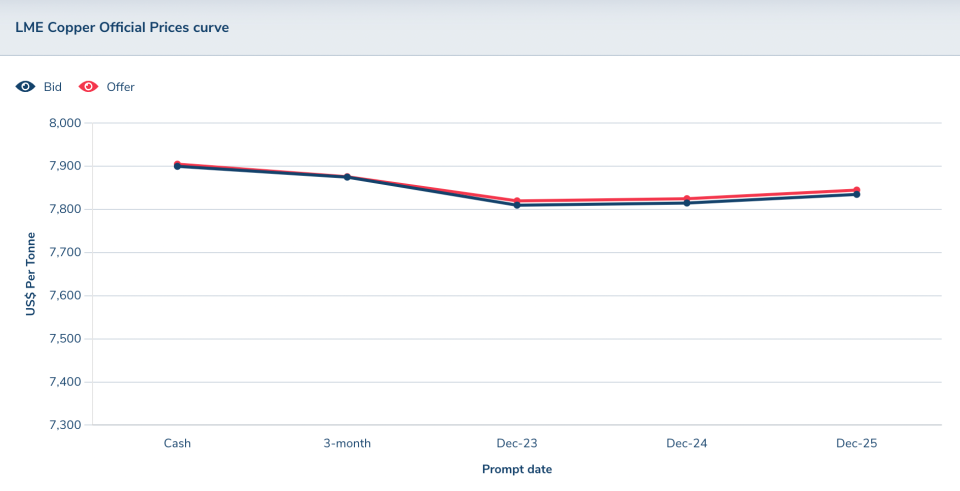

Despite its role in the green transition, copper has lost all the gains it made this year amid soaring energy costs, inflation and China’s zero-Covid policy which have cut demand expectations.

Prices on the London Metal Exchange were down around 30 per cent in October from their peak in February when Russia, when the three-month LME copper price reached a massive $10,580 per tonne.

Mikanikrezai expected Chinese markets to recover in time for the second quarter, with investors waiting for its policies to shift.

He believed current prices did not reflect the “growing tightness under the hood”, with investors overlooking potential shortages as countries continue to grapple for resources.

This comes in a climate where demand for copper has remained robust.

Commerzbank analyst Carsten Fritsch argued that copper demand has been resilient despite falls in prices over recent months, suggesting a strong appetite for the metal.

He said: “Copper imports have at least proven robust of late. If this remains the case, or if they even pick up further, sentiment would probably stabilise.”

Fritsch also believed there was unlikely be a quick turnaround, and prices have instead been driven by tailwinds such as production cuts at Peruvian Las Bambas mine – which accounts for two per cent of global production.

Markets rebounded last week amid renewed expectations China could further ease restrictions and boost demand, climbing as much as 7.4 per cent in Friday’s trading.

Three-month contracts trade at $7,895 per tonne on Friday, their highest levels since mid-September.