The vote-winning power of tax cuts

As theGeneral Election clunks into gear, it’s already clear what Labour’s approach will be: promise to spend literally all the money.

The Tories put out a dossier at the weekend costing the opposition’s pledges at a jaw-dropping £1.2 trillion.

You can quibble with the detail, but it’s pretty clear that under John McDonnell’s guidance, the British state would become the fiscal equivalent of Monty Python’s Mr Creosote — a wobbling, quivering leviathan attempting to stuff billion after billion down its rapacious maw.

On the Tory side, however, there is more uncertainty. Sajid Javid’s new fiscal rules allow him significant space for extra infrastructure investment, but still require relative restraint when it comes to day-to-day spending — reportedly a source of tension with others involved in the campaign, who wanted to loosen the purse strings more significantly.

The chancellor does, however, have room for a few election goodies. And the question that looms largest is whether these will take the form of extra spending, or whether there might be some room for a few tax cuts as well.

Closely allied to this, of course, is the question of what the voters want. There has been some brisk debate on this point between various policy wonks.

Essentially, most polling shows that people prioritise spending on public services over tax cuts, and that the level of taxation (and even the state of the economy) isn’t a pressing concern. The rebuttal to this is that people also say cite the cost of living as the most important issue they face — and tax plays a huge part in that.

But more interesting than the question of whether people want tax cuts, in many ways, is the question of what taxes they want to cut.

On this score, the TaxPayers’ Alliance think tank has carried out an invaluable polling exercise, testing a huge range of policy options on voters of all kinds.

What comes through extremely strongly is that there are indeed taxes people would like to see cut — and they tend to be taxes of a very particular kind. Namely, those that punish aspiration and enterprise, that stop people — especially those with small businesses or small incomes, struggling to get by and get on — from fulfilling their potential.

For example, the idea of Opportunity Zones (also proposed by our own think tank) gets a thumping endorsement. This is the proposal to give deprived areas of the country the chance to cut taxes and take other measures to boost their prosperity.

But that’s only the start of it.

Other popular policies include stamp duty exemptions for small firms and hiking the threshold to £1 million for everyone, three-year corporation tax holidays for startups, cutting business rates on the high street, capping council tax rises, cutting tax on the self-employed and small businesses, dropping the basic rate of income tax, reducing PAYE to encourage employment, abolishing the TV licence, linking tax thresholds to inflation or wage growth, and ensuring that people aren’t taxed on the profits when they sell their family home.

All of these received landslide support, among voters of all types. There was also strong support, though less utterly one-sided, for reducing corporation tax rates to 12.5 per cent to match Ireland’s, and cutting fuel duty and road tax to make driving cheaper.

And, as the TaxPayers’ Alliance points out, traditional working-class Labour voters were just as likely to embrace these ideas as affluent Tories. In fact, support for ideas like corporation tax holidays for new firms was markedly higher towards the bottom of the income scale.

It’s also instructive to see which tax cuts voters don’t support. Disappointingly for many City A.M. readers, cutting the top rate of tax to 40p appears to be a non-starter, at least in terms of the popular reception.

Indeed, most people would apparently like to see a new 50p band for those on £80,000 or more (though in separate polling, they told our think tank that everyone should be able to keep at least half of what they earn, which would no longer be the case with a 50p tax band once National Insurance was factored in).

Likewise, voters of all stripes favoured thumping taxes on second homes, and spending more on council housing.

Voters, in other words, are solid and pragmatic types. They want taxes cut where they are an obstacle to making work or effort pay. They are happy for the rich to get on — but they want to make sure that they pay their fair share and stop hogging all the houses.

They also, incidentally, think that Margaret Thatcher was comfortably the best Prime Minister of the last 30 years.

We will find out soon enough what the Conservatives will be promising the voters in their manifesto. Let’s hope that this time — unlike in 2017 — it includes addressing at least some of these concerns, and giving voters a bit more of their own money to spend in the process.

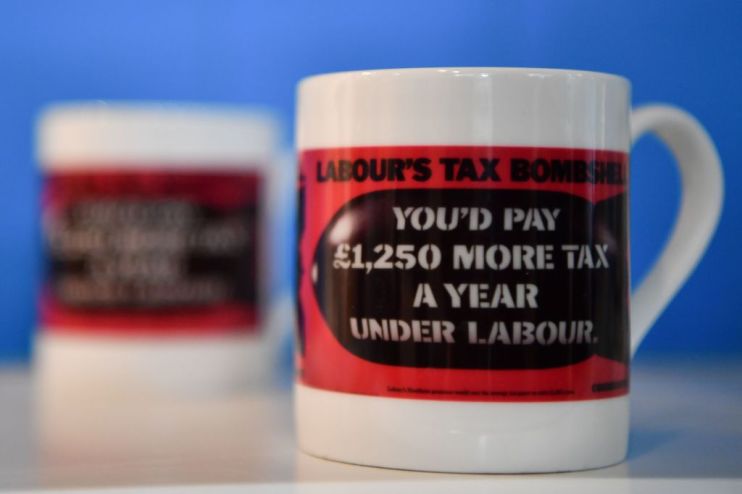

Main image credit: Getty