The power of capitalism: Don’t underestimate Reagan’s revolution

In the latest in his series, Dr Rainer Zitelmann – the historian, sociologist and author of new book The Power of Capitalism – looks at the Reagan years

The popular image of the US is as a textbook example of a free-market economy.

But in the 1970s, the U.S. was plagued by an ever-growing array of problems, most of which were the result of excessive government intervention in the economy and the proliferation of welfare programmes.

Adjusted for inflation and population growth, per-capita federal spending on welfare programmes almost doubled from $1,293 in 1970 to $2,555 in 1980.

Many US citizens’ economic situation had deteriorated prior to the arrival of Ronald Reagan in the White House. In real terms, white American household incomes dropped by 2.2 per cent between 1973 and 1981, while African Americans saw their household incomes shrink by 4.4 per cent. Worst off were the poorest 25 per cent of the overall population, whose incomes dropped by 5 per cent. At the other end of the income spectrum, high earners were squeezed with tax rates of up to 70 per cent.

Unemployment had risen to 7.6 per cent by the time Reagan took office, while inflation had stood at over 10 per cent for three consecutive years, climbing to 13.5 per cent – the highest level since 1947 – in 1980.

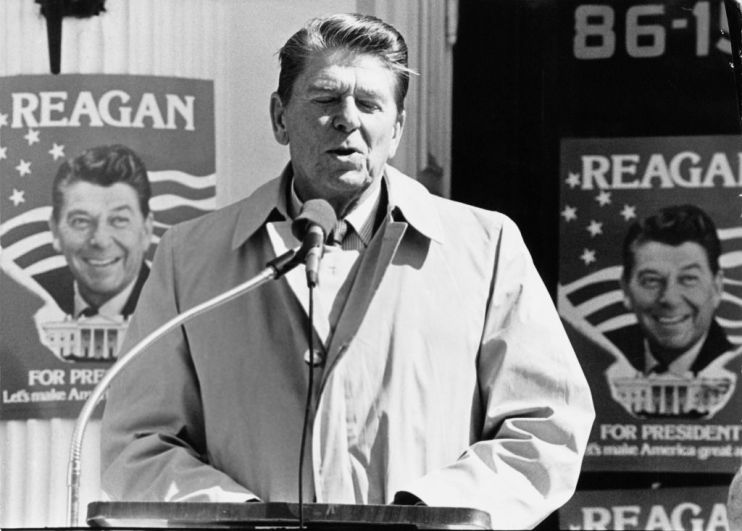

In other words, Reagan took office when the economic outlook was bleak. Having grown up in a modest home, he started his career as a radio announcer before moving to film with acting roles in over 50 Hollywood films. Between 1967 and 1975, he served two terms as governor of California, where he successfully balanced the budget and achieved a significant economic recovery.

In 1980’s Presidential election, Reagan won 44 states, a large majority of the electoral vote (489 to 49) and 50.7 per cent of the popular vote in his landslide victory over the incumbent president, Jimmy Carter. His inaugural address conveyed a simple message: “In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem”. Some years later, he would famously say: “The most terrifying words in the English language are: ‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help’”.

Reagan’s political agenda was a simple one: restricting the influence of the state in the economic sphere and increasing the role of the free market. In order to restore a more robust version of capitalism, he reduced bureaucracy, abolished unnecessary restrictions and slashed taxes from 70 per cent to 28 per cent.

By the end of Reagan’s second term, the US economy was almost one third larger than when he first took office. Between 1981 and 1989, 17 million new jobs were created. Inflation was in double digits when Reagan arrived at the White House. By the end of his second term, it stood at only 4.1 per cent, largely due to the prudent monetary policy of Paul Volcker, chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1979 to 1987. Although well aware that it would cause a temporary recession, Reagan explicitly supported Volcker’s strategy. Contrary to the dire predictions of many of his critics, his drastic tax cuts did not lead to further increases in inflation.

Reagan’s critics like to point to one statistic in particular to show what was wrong with his economic policy: national debt doubled from $1 to $2 trillion during his presidency. The growing accumulation of debt was caused by Reagan’s large military expenditure, which saw the defence budget almost double. The cumulative increase in defence spending even outpaced the cumulative increase in the budget deficit. If not for this massive increase in military spending, Reagan would have succeeded in cutting taxes and debt while creating jobs and getting inflation under control.

However, the second key issue confronting the Reagan administration – the Cold War, which the president proposed to end by massively escalating the arms race – made this impossible to achieve. That was the price for the West winning the Cold War and the Soviet Union collapsing.

The American Dream of income mobility was alive and well in the 1980s: 86 per cent of households that were in the poorest income quintile in 1981 were able to move up the economic ladder into a higher quintile by 1990. African American households saw even stronger growth in real take-home pay between 1981 and 1988 than their white peers. This disproves the legend of anti-capitalists, that only “rich whites” benefited from Reagan’s tax cuts.

Rainer Zitelmann’s book is available on the book’s website