The Inflation Game: War, Peace and the Perils of Central Banking

The descent is always more sudden than the increase; a balloon that has been punctured does not deflate in an orderly way.

— John Kenneth Galbraith

I travelled with my family to London and Normandy in July 2022. Our primary purpose was to meet up in France with my father-in-law, who had dreamed of visiting the sites where the tide turned in World War II. I did not realise that our excursion would have so much relevance to today’s economic conditions.

On 21 September, the US Federal Reserve intensified its attack on inflation with its third consecutive 75 basis point hike to the federal funds rate. The Fed also warned that more monetary tightening was forthcoming and would continue for at least the next year.

The Fed is in a difficult position: it must prepare the public for impending economic pain but without inciting a panic. The reality, however, is that a recession is now a virtual inevitability. Why? Because the Fed can only use blunt policy tools to reverse what have become extreme economic conditions. This makes it extraordinarily difficult to engineer a soft landing. The last two comparable events, the 1920 and 1979-to-1981 tightening cycles, both triggered severe economic contractions.

Threadneedle Street and threading the needle

During our visit to London, my son and I visited Threadneedle Street and the Bank of England Museum, where we played the ‘Inflation Game’.

The goal is to balance a steel ball at the mid-point of an air tube denoted with a two per cent inflation marker. The player — or an annoying father — then pushes an ‘economic shock’ button. This sends the ball to either the extreme right, which represents inflation, or to the extreme left, which represents deflation. My son struggled to return the ball to the target, overshooting several times before getting it to settle back on two per cent.

Image courtesy of Mark J. Higgins, CFA, CFP®

The Inflation Game is a perfect metaphor for the Fed’s predicament since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in March 2020.

First, the massive economic shock sent the ball careening to the left. The Fed and the federal government responded by flooding the economy with liquidity to ward off extreme deflation and a potential depression. Then, in 2022, after the excessive stimulus had shifted the ball too far to the right, leading to high inflation, the Fed reversed course. It will almost certainly overshoot the target again, only in the other direction, before it can finesse a return to the comfortable two per cent target.

The Great Depression’s human toll

This monetary tightening will have consequences — the ball has simply strayed too far from the midpoint. This will produce economic pain in the form of declining asset values, job losses and general anxiety about the future. That does not mean that the Fed takes its responsibility lightly. The Fed’s leadership knows that its policies will cause short-term pain. But it also knows that the long-term consequences of policy blunders — or of doing nothing — are much more severe.

This brings us to the second stop on our trip: Normandy. That World War II broke out less than 10 years after the start of the Great Depression is no coincidence. In 1929, the Nazi party was on the verge of collapse. The German economy was recovering from the devastating hyperinflation of the early 1920s, and renewed optimism was taking root. In the 1928 elections, the Nazis won only 12 of the 491 seats in the Reichstag. But then the Great Depression hit. Millions of Germans joined the ranks of the unemployed, and the economic decline seemed to have no bottom. In the September 1930 elections, the Nazis won 107 out of 577 seats and set about dismantling the Weimar Republic.

The experience of the 1930s and 1940s is worth remembering. When central bankers flood the market with liquidity to forestall a Great Depression-level event, their primary goal is not to prop up stock prices but to save lives. Would World War II, and all its horrors, have occurred without the Great Depression? Probably not. Could similar disasters have developed in 2020 — or 2008 — had central bankers and government policymakers throughout the world failed to stop the panic? It’s a distinct possibility.

The Great Inflation and The Misery Index

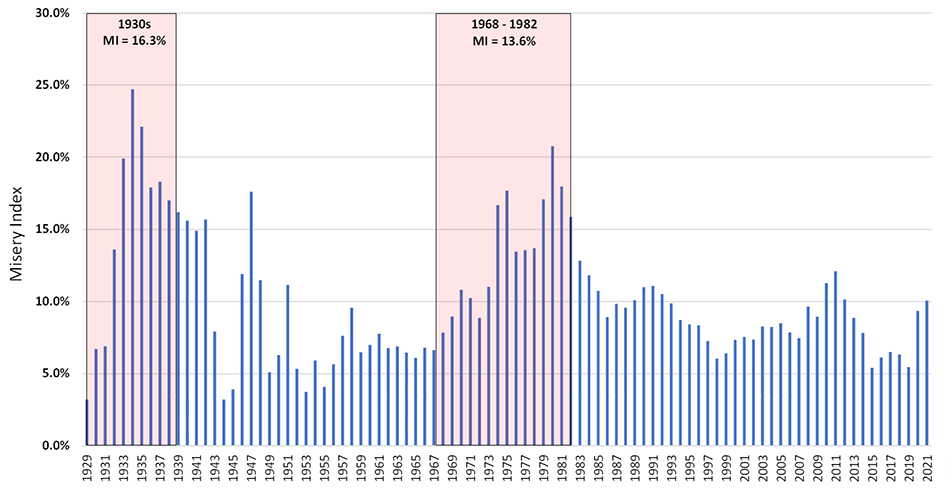

The dislocations of the Great Inflation from the late 1960s to early 1980s caused similar levels of deprivation in the US. The Misery Index, which adds the inflation rate and the unemployment rate, reflects this. During the worst years of the Great Inflation, Misery Index readings were almost as bad as they were during the Great Depression. The average Misery Index from the peak period of the Great Inflation from 1968 to 1982 was 13.6 per cent, versus 16.3 per cent during the 1930s.

The US Misery Index, 1929 to 2021*

*The official Misery Index begins in 1948. Unemployment and inflation data used to calculate the Misery Index prior to 1948 is based on a different methodology. Nevertheless, the general trend is likely to be directionally correct.

History demonstrates that economic suffering breeds popular discontent, which in turn, breeds civil unrest and violence. That’s what happened amid the Great Inflation of the late 1960s and 1970s in the US. Indeed, the misery of the Great Inflation was even more insidious than that of the Great Depression. An economic collapse is easily understood as a source of suffering. The debilitating anxiety caused by constant price spikes is harder to grasp. It took the foresight and courage of Fed chair Paul Volcker to magnify the pain temporarily to rein inflation in over the long term.

The Fed’s near-impossible task

The Fed and other public officials are easy to criticise. But their quick action in response to the pandemic kept the US economy from spiralling into another Great Depression.

Their current efforts are intended to counteract a reprise of the Great Inflation. Neither the Great Depression nor the Great Inflation is an event that anyone would wish to repeat.

Over the coming year, there will undoubtedly be more pain before the US economy returns to a sense of normalcy. And even when it does, new challenges will emerge. I am crossing my fingers that the Fed will somehow thread the needle and orchestrate a soft landing. But if it fails, it won’t be because of personality flaws or professional incompetence. It will be because of the near impossibility of the task.

Rather than blame the Fed for the pain we will likely experience in the near term, we need to keep our eye on the ball and remember that returning inflation to the two per cent target is our most important priority.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

By Mark J. Higgins, CFA, CFP, seasoned investment adviser with more than a dozen years of experience serving large institutional investors, such as endowments, foundations, public pension plans, and corporate operating reserves.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photograph Division/ Original drawing by Edmund S. Valtman.