The FTSE 100 has done us all dirty… again

The FTSE 100 has done us all dirty yet – again.

Over and over it marches us up a hill only to send us back down again.

Former Bank of England governor Mark Carney is often referred to as the “unreliable boyfriend” of monetary policy making for his comments signalling he and the MPC would raise interest rates, only for them to sit on their hands.

For investors, that title would probably be better suited to the Footsie.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

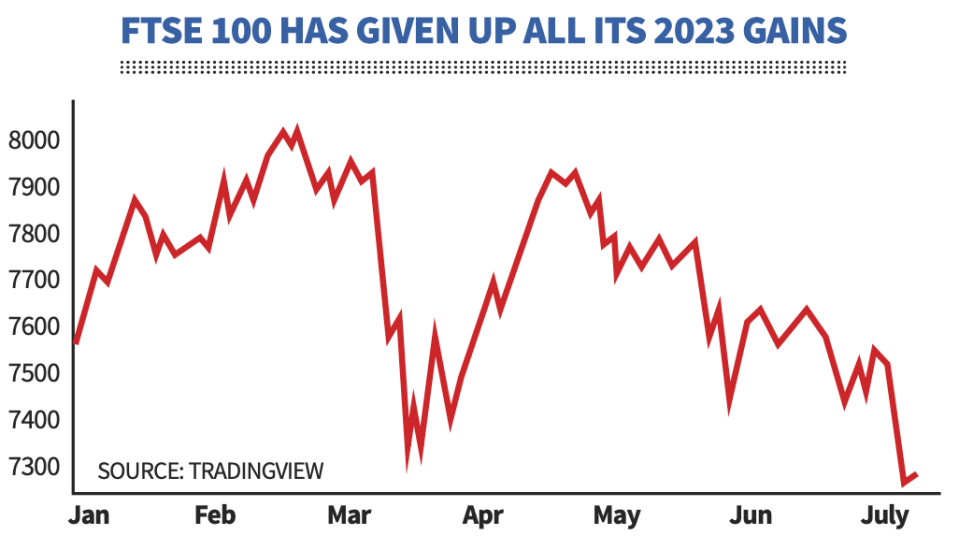

At the start of the year, the index of Britain’s top companies raced out of the blocks. It powered far ahead of its Wall Street rivals the S&P 500, Dow Jones and Nasdaq. It also was beating away a challenge from Europe’s equivalent, the Stoxx 600.

February rolled around, and a landmark was smashed. For the first time ever, the FTSE 100 breached the 8,000 point threshold.

Reams and reams of column inches were dedicated to hailing the return of the London markets. This was to be the rebirth of the City, spearheaded by its flagship index.

The fundamentals were there.

Energy prices, though lower than their peaks reached in the immediate aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, were said to be on a higher trajectory.

Good news for the big oil and gas firms (Shell and BP) that represent a big chunk of the FTSE 100.

China’s economic recovery was just getting under way after Beijing finally scrapped their zero Covid-19 policy. A fresh injection of demand into international commodity markets from the world’s largest consumer of raw materials could only be a boost for the FTSE’s miners.

Bizarrely, and perhaps with a pinch of hyperbole, some of the indexes’ constituents have been benefitting from the cost of living crisis.

B&M, the budget retailer, is among the best performers this year, up around 30 per cent, likely because Brits have been trading down to avoid skyrocketing prices among those pesky profiteering supermarkets.

The biggest upside for the FTSE in early 2023 was undoubtedly conviction over inflation’s steady drop. Not only would that have eased pressure on household finances, it would have prevented what are now some pretty wild bets on peak interest rates (see JP Morgan’s seven per cent wager last week).

Blueprints were drawn. Pillars constructed. The FTSE 100 was ready to clinch the top index title this year.

Oh how wrong we were – again.

A really bad recent run of form has whittled away the FTSE’s 2023 gains. In fact, it is now down about 2.6 per cent. At its peak, the index’s advances were getting on for 10 per cent.

It’s obvious to see why such a fall from grace unfolded. Banking collapses in the US and Europe compelled traders globally to retreat from stock markets.

There was a genuine prospect of a tough 2009-style credit crunch gripping the global economy due to banks retaining cash for fear of lending to poorly managed outfits like Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic and squeezed consumers.

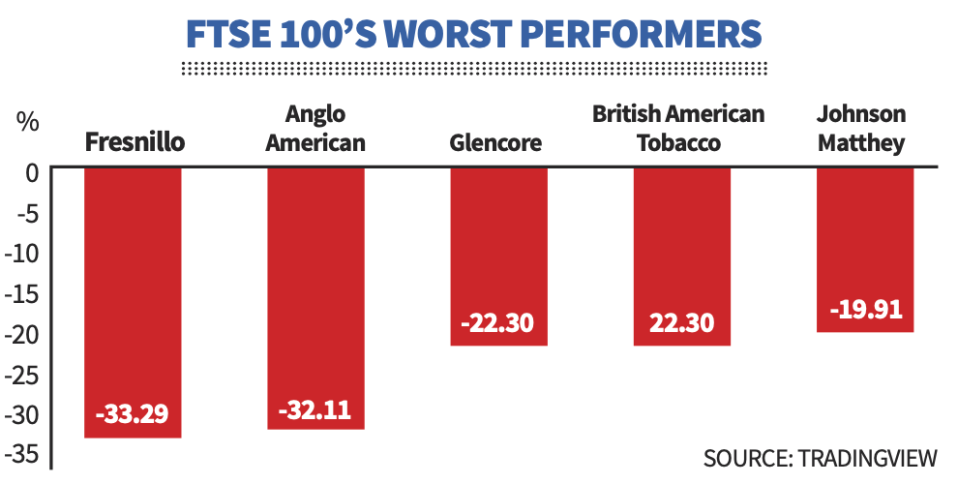

Data from Caixin – a private research firm – has consistently shown China’s pick up from the pandemic is fraying. The country’s manufacturing and services PMIs are getting close to crossing the 50 point threshold that separates growth and contraction.

Weaker spending in the world’s second largest economy spells danger for the FTSE’s big players like Glencore and Rio Tinto.

Domestic instead of global factors are now by far the heaviest factor weighing on British stocks.

Recession risks are amping up. No one wants to be a stakeholder in a flagging economy.

So in short the FTSE 100 has responded as one might expect amid a downturn – badly.

Across the pond, Wall Street is booming as the US flirts with a recession. Perhaps the UK’s premier index is therefore a more accurate reflection of its economy than its US counterpart.

But how London would love to have the ear of investors as New York does.

The start of the year promised so much.

WHAT I’M READING

Britain’s yield curve last week was the most inverted it has ever been in 23 years, Capital Economics pointed out in a recent note to clients. That’s a function of traders ditching gilts at an alarming pace of late. An important point must be made here. Britain is not running out of money. In fact, it runs budget deficits more often than not. The same goes for most rich countries. Instead, investors are both pricing in more interest rate rises from the Bank of England to tame inflation and demanding greater compensation for holding assets which have returns that are being eaten up by price increases. Yes, a government borrowing cash will put upward pressure on bond yields. That is not the same as its coffers running dry.