The Bitcoin halvening is happening but you’ll be missing the bigger picture

Around the 12th May, Bitcoin will be having its long anticipated third halvening. While the focus has been on the bitcoin network itself and its correspondence to Bitcoin’s status as a digital ‘hard money’, I argue most onlookers will be missing the bigger picture.

Bitcoin’s block reward to miners will be cut by 50% at block 630,000 (issuing 6.25 BTC per block instead of 12.5 BTC). From inception, Bitcoin was designed as a deflationary currency meaning the network issuance rewarded to miners for securing the network falls every 4 years until all 21m BTC units have been mined. But unlike the previous two halvenings, this occurrence is particularly salient as it comes at a time of massive economic and political uncertainty, with Governments issuing unprecedented levels of debt to counter the economic instability caused by the COVID-19 disease.

It’s perhaps no surprise that the notion of ‘hard money’ has become a central focus for people both inside and outside the crypto ecosystem with macro investor Paul Thomas Tudor revealing last week his fund has been investing in Bitcoin as a hedge against the possibility of future inflation by central banks. Huge fiscal spending globally may explain, at least in part, why the halvening is attracting attention from individuals like never before.

But while analysis of the halvening has been mainly focussed on Bitcoin itself, you may be surprised to learn that such halvenings have indirect effects elsewhere, namely open finance. There has been a long history of developers extending the capabilities of Bitcoin (see Taproot, Rootstock) but recently more developers are looking to cross-chain solutions that ‘port’ BTC over to more expressive smart contracting platforms, such as Ethereum – the stomping ground of open finance development.

Having BTC interoperate with other blockchains is no trivial feat for developers but there are clear incentives that make such endeavours worthwhile. For one, Bitcoin can act as an effective collateral asset for many open finance applications not only because of its hard money properties and resilient social contract (epitomised through halvenings) but also because of its deep pools of liquidity and relatively low volatility compared to other cryptoassets today.

What this means in practice is that Bitcoin holders can tokenise their BTC (1:1 peg) on Ethereum and utilise them in a variety of different decentralised applications all without having to give up their BTC themselves. Additionally, Ethereum users are able to get exposure to Bitcoin without leaving the world of open finance. The downside you might be asking? Bitcoin and Ethereum start becoming reliant on each other’s network security.

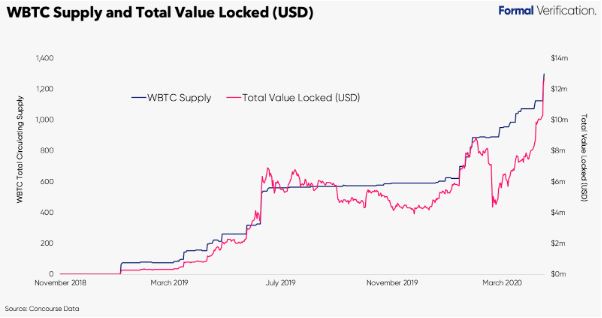

While still early days, Ethereum has two live (and centralised) implementations of BTC pegs (WBTC, imBTC) that can interoperate with open finance. WBTC has gained popularity in recent months with 1.3k WBTC ($12.6m) being issued on Ethereum from users locking the equivalent amount in BTC. Other implementations approaches are being developed (see tBTC, sBTC, RenBTC, pBTC) each designed with unique pegging models that provide different trade-offs in both scalability and security.

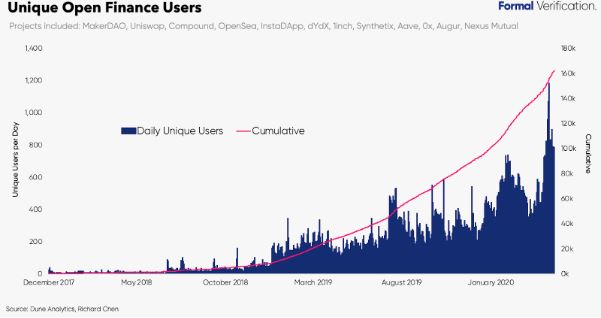

Let’s examine how Bitcoin can play a key role in an already flourishing open finance ecosystem. Today, total unique users interacting with open finance applications has grown to 163k (note addresses aren’t a perfect measure as multiple addresses can be used by the same user). Using recent growth rate of 0.3% daily, we can expect 1m users by August 2021. However, weaving Bitcoin into the wider fabric of open finance, with all of its liquidity, users, and attractiveness as a hard money asset, can throttle further growth.

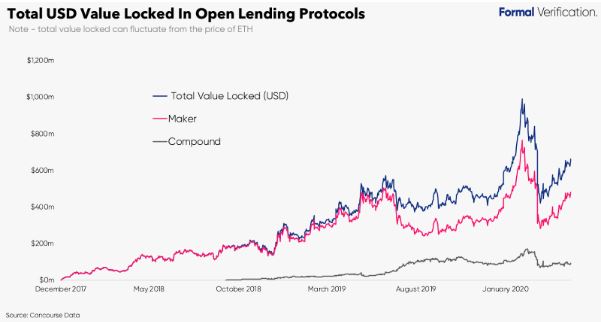

Let’s take the largest segment of open finance which is the lending market, with $660m now locked in lending protocols (all-time high of $993m Feb 2020). MakerDAO, the largest decentralised credit platform on Ethereum, allows users to loan themselves Dai (a decentralised stablecoin pegged to USD) up to 66% of their collateral market value. The platform currently has a respectable $482m of value locked up from 15k+ unique debt position holders.

Now, ~90% of total Dai debt on MakerDAO is collateralised by ETH which so far has aided in the distribution of 121m Dai (~$121m) into the open finance ecosystem. However, users may perceive (and use) Bitcoin synthetics as less risky collateral assets once they become available due to Bitcoin’s store-of-value narrative and market profile (e.g. BTC’s 1Y volatility of 0.67 vs. ETH’s 0.75). The second order effect in this case would be an increased appetite in self-issued loans, increasing the liquidity of the stablecoin Dai in the wider open finance markets.

Moreover, Compound, a P2P algorithmic money market protocol on Ethereum with ~$100m worth of assets locked, lets users permissionlessly borrow or lend crypto against collateral. Similar to Maker, Compound may offer Bitcoin synthetics as collateral options essentially allowing users to lend or borrow out Bitcoin assets trustlessly. Furthermore, integrating these synthetics to Compound would be relatively easy for developers to implement, requiring no major architectural changes to the underlying application thanks to open-source composability.

In sum, Bitcoin as a hard money has the ability to unlock credit markets orders of magnitude larger than seen today. Whether Bitcoin investors know it or not, Bitcoin isn’t just an option of a future store-of-value but also an asset that plays an indispensable role in the much wider parallel financial system that is open finance.

This is not to say that focusing internally to Bitcoin during halvenings is erroneous, quite the contrary. Halvenings are precisely what feeds into Bitcoin’s unique hard money social contract. But we should equally be looking outwards and continuously challenging our understanding of how interoperable decentralised networks can impact one another. As Thomas Kuhn noted, true scientific revolutions require “the reconstruction of prior theory and re-evaluation of prior fact, an intrinsically revolutionary process that is seldom completed by a single man and never overnight”.

But that’s all part of the fun, and the journey.

References: Kuhn, T., 1970. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Author: Lewis Harland, Author of Formal Verification can you make ‘Formal Verification’