The Big Short interview with director Adam McKay: “Outrage with banks comes naturally… they’re street hustlers”

The Oscar-nominated director of financial film The Big Short, Adam McKay, wasn't afraid of throwing the cat among the pigeons when I caught up with him yesterday. On the eve of his latest film's release he launched a stinging attack on Wall Street, branding bankers “street hustlers” and labelling the SEC’s response to the crisis “disgusting”.

Adam McKay, who is nominated for the Best Picture and Best Director gongs, said that banks in the US “have completely captured the government”.

The Big Short, which stars Christian Bale, Brad Pitt and Ryan Gosling, tells the story of the handful of financial outsiders who predicted the 2008 crash and shorted the housing market. Readers of this newspaper may take umbrage with the film’s portrayal of bankers, but they'd struggle to find fault with his super-stylish, nerve-frayingly tense account of the months leading up to the crash.

The director also had some fruity suggestions for improving the banking sector, including: “Maybe they should be not-for-profit institutions. I think there should be a reassessment of what banks are in our society because they are so essential to everything. I’d love to see a transaction tax in the US to lower the volume of trading… capital requirements increased… a derivatives clearing house that isn’t so easily gamed.”

McKay added that some of the world's leading economists are fans of The Big Short, saying former governor of the Bank of England Mervyn King is a fan of the movie, as is US economist Paul Krugman. See the full interview after the trailer below, followed by my review.

What attracted you to the movie?

I read the [2010 Michael Lewis] book The Big Short and it just got under my skin. I thought it was one of the more amazing books of this era and I couldn’t get it out of my head. When I got the chance I jumped at it.

I had a very close family member lose their home [in the crisis] and a lot of friends who lost their jobs. I was lucky to be working in movies in LA so it didn’t put me out of work but the studios were cutting down on the number of movies they were making and we had two companies we had to downsize. It wasn't pleasant.

How would you describe the film?

The exciting thing about this movie it that it’s real-life so it doesn’t adhere to any one genre: there are parts that are funny, parts that are dramatic, informative. So I think what I was excited about was telling stories that aren’t pure comedy or pure drama. This was a living, breathing story. Every day on set we were talking about articles that were in the paper and we had this sense we were breathing this story while we were making it.

Was it difficult overcoming the complex subject matter?

At the centre of the movie were these great characters that Christian Bale, Ryan Gosling, Steve Carell and Brad Pitt played. What I liked about is that it’s a true story, so there was no need to gild it or amplify it. What these characters went through was the meat of the movie… Some of these guys started to feel terrible as their whole world challenged them, said they were crazy. I really wanted the movie to have that sweat to it, that tension and uncertainty.

Steve Carell plays a world-weary motor-mouth with an axe to grind

Steve Carell plays a world-weary motor-mouth with an axe to grind

Why have we never had a great financial crisis movie?

I think part of the reason is the jargon the banks use – they go out of their way to make us all feel confused, that they’re experts and we can’t understand the language. there’s this general belief that banking and finance is so complicated that, you know, how could any average person understand it? [But] financial complexity is just a way to disguise fraudulent hiding of risk, which bubbled up and turned into a contagion and spread around the world. I realised that terms like CDO and CDS were really just gussied up, confusing words for moving debt and money around.

Were you worried about the potential backlash?

We went out of our way to make sure we didn’t single out any individuals as villains. We saw it as a systemic failure – banking just got too powerful. [But] we were praying for a backlash – we wanted to reignite this discussion. There was this bogus narrative that was sold by the big banks about how government caused the collapse.

There are a lot of people working very hard to make the big banks look like they accidentally stepped in it when the truth is they worked 30 years creating this system of derivatives and they made billions of dollars out of it – it’s far from an accident. The great thing is the data is all very clear, so despite these bizarre fringey op-eds, the movie is holding well and has a lot of support from a lot of big names. Mervyn King saw it and really loved it and Paul Krugman wrote a piece defending the movie.

What’s your take on the legacy of the crisis?

I wish the movie wasn’t quite as relevant as it is right now, I wish [the current economy] were in a better spot… After 2008, 2009 we had some reform in the US with Dodd-Frank, which had some good stuff in it but then the conversation shut down and everyone acted as if everything was fine.

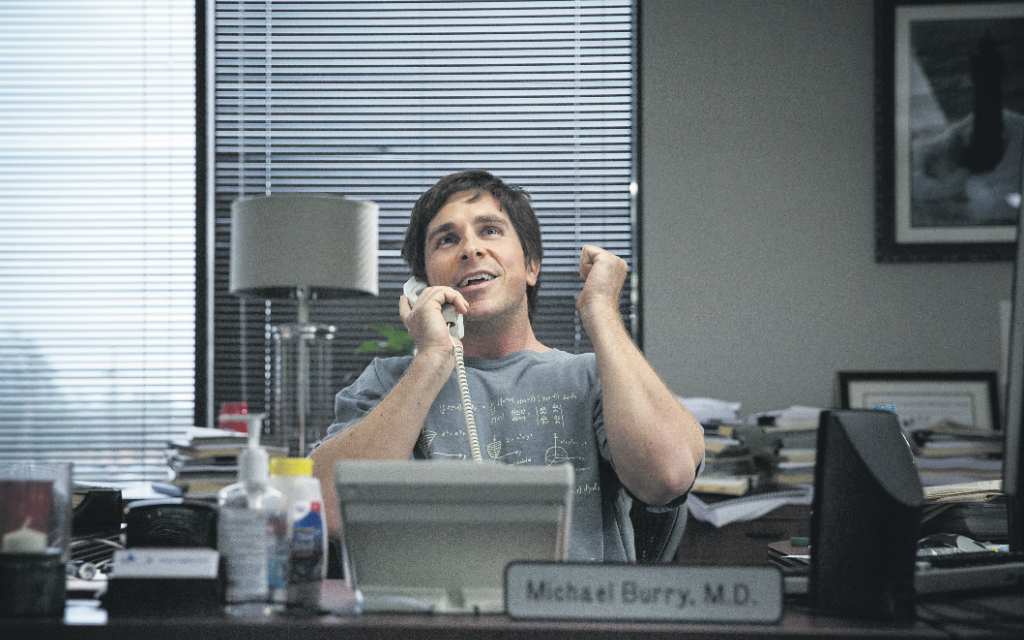

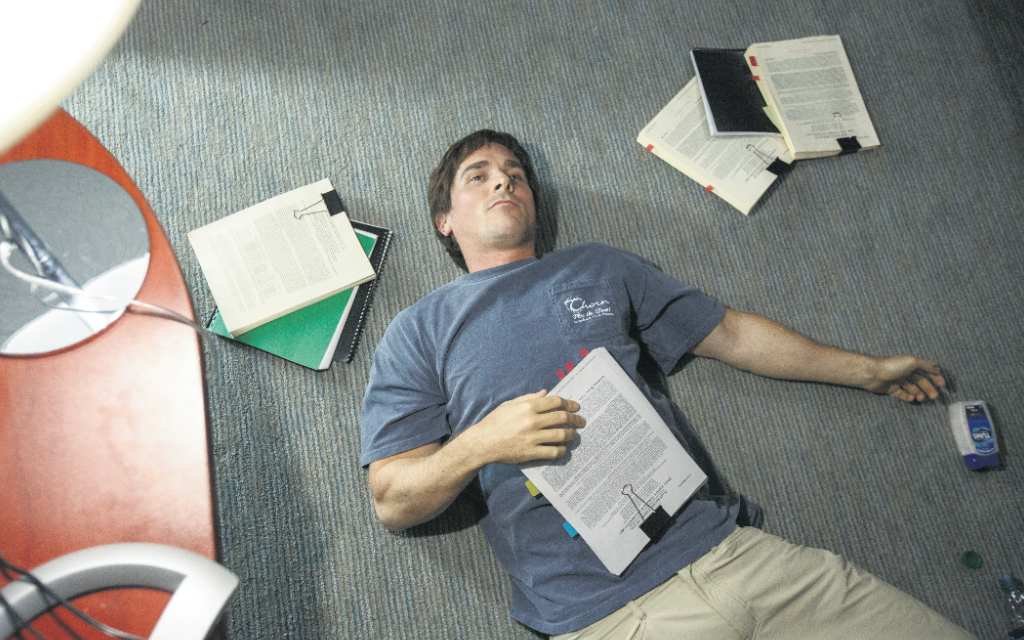

Christian Bale is on blistering form as a heavy metal-loving trader

Christian Bale is on blistering form as a heavy metal-loving trader

[The SEC’s response] was disgusting. The main problem is the banks have completely captured the government in the US and that’s not been remotely addressed. Until that’s addressed you’ve still got a kid with the keys to the candy store. I’d love to see a transaction tax in the US to lower the volume of trading; I’d love to see capital requirements increased; I’d like a derivatives clearing house that isn’t so easily gamed. Maybe [banks] should be not for-profit institutions. There should be a reassessment of what banks are in our society because they are so essential to everything but they run around like they’re hustling on a street corner.

In the US the recovery is so focused on the top one per cent and so flat for the 99 percent that there’s a dissatisfaction that we’re seeing in both positive and negative ways, with the emergence of a demagogueic cartoon figure like Donald Trump, and in a positive way with someone like Bernie Sanders. It seems to be happening worldwide; in Australia and Canada and the UK’s new head of the Labour Party. There seems to be a current of change. People get it: whether or not they get it intellectually they can feel that the austerity push that went on was a coded trick for taking away resources from the people and making sure the recovery went into the hands of the one per cent. A lot of countries fell for that. In the US we had a stimulus, which helped a lot but there were certain aspects of our recovery that went under the heading of austerity and quickly you realise that’s not the road and it’s a way to shift power and assets.

What's coming next?

I wouldn’t be surprised if I worked on [more] stories that are happening right now. We’re at such a crossroads with modern civilisation that it’s exciting and horrifying. To ignore that is foolish, especially as a filmmaker.

I was kicking around an idea with Will Ferrell and John C Riley about immigration, about immigration, two hapless Americans that go down to protect the border with Mexico, which would be more comedic. Then I have another idea that’s a little more ambitious about climate change that I’m trying to put together, which is a very hard subject to crack… Climate change is the biggest story in the history of mankind. It’s the biggest story in the history of our species.

Steve Carell stars opposite Ryan Gosling, who sports a hideous perma-tan

Steve Carell stars opposite Ryan Gosling, who sports a hideous perma-tan

OUR REVIEW

The Big Short | ★★★★☆

Adam McKay’s epic financial crisis movie could have the alternative title “The Real American Hustle”. In McKay’s movie, that’s what caused the crash: hustle. Not by one man or one bank, but by everyone, at every level of the food chain, from frat-boy mortgage brokers on the streets of Miami to the ratings agencies shoring up their business to the heads of the biggest banks. Everybody was on the game, high on their own success, carving off slices of the endless pie.

But this story isn’t told by the hustlers: it’s told by the handful of people – misfits one and all – who sensed the impending tsunami before it hit.

Michael Burry, played by Christian Bale, was one of these men. He’s the kind of guy who sincerely says things like “that’s a nice haircut, did you do it yourself?” before gambling $1.3bn of his firms money shorting the housing market. Another is Ryan Gosling’s Jared Vennett, a banker himself, albeit one who’s willing to bet against his own team, because that’s the kind of oily, malefic human being he is.

Director McKay, previously known for comedies including Anchor Man and Taledega Nights, turns the complexity of mortgage backed securities into an advantage, making a joke out of their apparent indecipherability. Instead of explaining the film’s more difficult concepts through the narrative, he cuts to Margot Robbie in a bubble bath, or to Selina Gomez at a roulette table, creating surreal riffs on collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps.

While the first half of the film tends towards comedy, the second lurches face-first into almost unbearable tension. Even the camera appears to be having a seizure, struggling to stay in focus, darting from character to character; it’s disorienting and sometimes physically uncomfortable. Suddenly it’s not funny anymore.

The Big Short captures the intoxication of the pre-crisis days and the dread and confusion that followed 2008, which most of our readers will remember all too well.

Sure, there’s a healthy portion of banker bashing that will raise the blood-pressure of some City A.M. readers, but those same people will be the ones laughing loudest at lines like: “What company treats their customers that badly and survives? OK, you’re right, Goldman.”