Taxpayer to hand over £150bn to Bank of England to cover QE losses

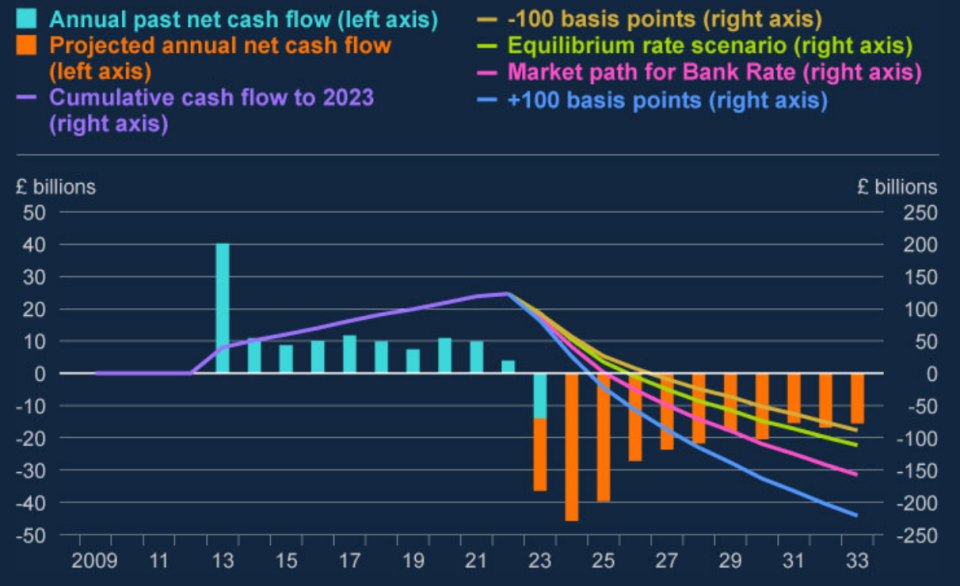

Taxpayers will have to foot a £150bn bill to cover cumulative losses on the Bank of England’s bond buying scheme over the coming decade, a new projection has claimed today.

The Treasury is forecast to inject hundreds of billions of pounds into the central bank’s balance sheet to make up for a shortfall in its quantitative easing (QE) programme.

According to a quarterly report by the Bank on its asset purchase facility – the vehicle it uses to hoover up UK debt on financial markets – losses from bond purchases are poised to balloon by the early 2030s.

After the 2008 financial crisis, the Bank of England started purchasing UK government and corporate debt from financial institutions in an effort to stimulate the economy by pushing down yields.

Under the arrangement, the Bank channels any profits made back to the Treasury, while the taxpayer foots the bill for losses.

More than a decade of ultra-low interest rates has resulted in the Bank generating a windfall for the public finances.

However, that dynamic has gone into reverse as a result of rising interest rates.

Interest the Bank pays on commercial bank deposits has risen sharply over the last couple years due to Threadneedle Street lifting borrowing costs to tame inflation.

It means returns the central bank makes on the bonds it has purchased are now being outstripped by what it pays out to its deposits.

Cash flow projection for QE programme

“When this arrangement was put in place it was recognised that reverse payments from HMT to the APF were likely to be needed in the future as Bank Rate increased,” the Bank said today.

Bond prices have also fallen quickly as traders have priced in more rate rises, adding to the Bank’s losses. Prices and yields move inversely.

The looming £150bn bill will amplify pressure on the UK’s already stretched public finances.

Experts at ratings agency Fitch today warned the UK this year will have the highest debt interest burden in the rich world for the first time since records began in the 1990s.

Money paid out to holders of UK government debt is set to reach 10.4 per cent of total government spending, Fitch said.

Others have been warning for some time that Britain’s debt interest bill will swell over the coming years.

A swelling debt pile tends to be viewed by economists as risky only if it grows faster than the economy.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecast at the March budget that debt interest spending as a share of government expenditure would hit around 11 per cent this year. Since then, market rate expectations have increased, meaning the figure is almost certainly higher.

In its fiscal risks report earlier this month, the budget watchdog said interest payments are set to be £13.7bn higher in 2027/28 compared to its March projection of £96.5bn.

The renewed warning on the imbalance in the public finances from Fitch raises questions over whether Chancellor Jeremy Hunt will launch tax cuts at the autumn statement.

In the March budget, the OBR judged him to have just £6.5bn of headroom against his fiscal targets of getting the debt stock falling and capping borrowing at three per cent of GDP in five years.

That’s the slimmest margin or error of any Chancellor since the OBR was created in 2010.