Taper Tantrum 2: is there a sequel in the making?

Sequels – occasionally they’re better (The Godfather Part II), but most of the time they’re worse. Often far worse (Jaws: The Revenge).

As investors and economists look for the next market risks after the pandemic, some are now expecting a follow-up to 2013’s blockbusting Taper Tantrum. This sequel could even be coming to (trading) screens near you as soon as 2021.

Whether it will be more enjoyable – or more dramatic – than the original remains to be seen.

What was the original Taper Tantrum?

The backstory centred on the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. As the whole financial sector teetered on the brink of collapse, the Federal Reserve (Fed) – directed by then-chair Ben Bernanke – introduced its now well-known policy of quantitative easing (QE).

This involved buying up large amounts of bonds and other securities, with the goal of increasing liquidity and stability in the financial system, and encouraging lending. This was supposed to stimulate economic growth by reducing the cost of borrowing, getting consumers spending and businesses investing again.

The policy worked. Between 2008 and 2013 the Fed bought almost $2 trillion in US government bonds (Treasuries) and other assets. Markets recovered strongly.

Arguably QE worked too well, as investors came to rely on this massive market support.

Then came the twist…

In 2013 Bernanke announced that the Fed would, at some point, start to reduce – or “taper” – the amount of asset purchases it was making.

In so doing, the Fed chair learned an important lesson in how not to script an exit strategy.

Investors – spooked that the world’s largest buyer of bonds was apparently exiting stage left – reacted badly to his announcement.

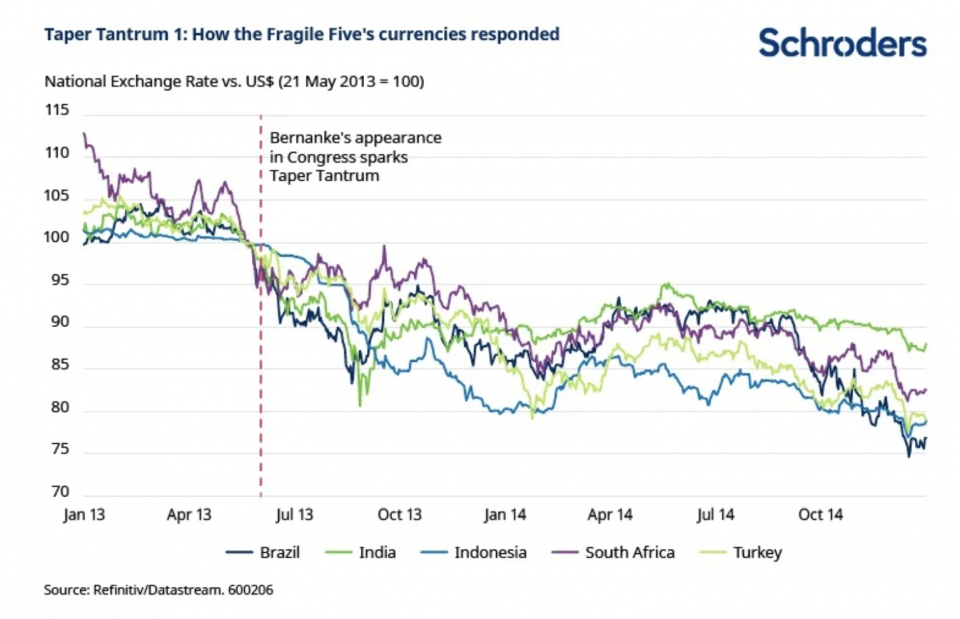

US Treasuries immediately sold off and the value of the US dollar shot up. Emerging markets suffered, particularly the “fragile five” of Brazil, India, Indonesia, Turkey and South Africa, as foreign capital was withdrawn and their currencies depreciated sharply.

This became known as the Taper Tantrum. It was called a tantrum as – like a child whose comfort blanket has been taken away – it was seen as an overreaction.

Once the tapering actually started, markets continued to recover rather than collapse.

Discover more from Schroders:

– Learn: Why climate change is creating a 1929 moment

– Read: Outlook 2021: A bright future?

– Watch: Time for investors to stop hibernating

What is the fear?

Speculation abounds that a big budget follow-up is in the making. This time, Covid-19 is the backdrop.

The level of support provided by governments and central banks since the pandemic swept the world dwarfs that of the first time around. This has helped economies to keep ticking over and markets to shrug off the effects of the virus and hit new highs.

The US government alone had spent around $2.6 trillion on fiscal stimulus packages by October 2020, most of which was accounted for by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) which totalled around $2 trillion.

Meanwhile, the Fed has helped prop up bond markets through its gargantuan QE programme. The Fed’s balance sheet (the total assets and liabilities it holds) has soared to $7 trillion.

Since June, the Fed has been buying $120 billion of Treasuries and mortgage-backed debt a month. The intention behind it was to stabilise markets, but also to support the economy by keeping long-term interest rates low. With bond yields and interest rates suppressed by this market support, investors have sought out riskier assets to generate their returns or meet their liabilities.

However, as vaccines continue to roll out and a return to normality becomes a less dim prospect, QE will moderate.

What next?

Our economists here at Schroders expect the pace of QE will moderate to around $100 billion per quarter in 2022 compared with its current pace of $360 billion.

As in 2013, anticipation of this may trigger another taper tantrum, causing US Treasury yields to spike higher and making investors more risk averse. Stock markets would fall and as investors pull back from funding risky assets, borrowers (be it a government or a company) may be less able to meet their debt payments.

The tightening in financial conditions for the government and companies may hurt growth as confidence takes a hit and expenditure is reined in. Meanwhile, an increase in bankruptcies would push unemployment higher.

In emerging markets, a ‘sudden stop’ and reversal of capital flows could cause currencies to depreciate sharply, forcing central banks to raise interest rates. The combination of foreign capital leaving and domestic demand declining would harm growth in emerging markets. Inflation would also likely be lower than expected.

It’s worth noting that our economists currently only place a 10% probability of Taper Tantrum 2 coming to fruition. After all, lessons have been learned from the original Taper Tantrum, not least in how to script the ending.

For the time being at least, the QE show must go on.

- Discover more from Schroders’ experts by visiting Schroders insights or following on twitter.

Important Information: This communication is marketing material. The views and opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) on this page, and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other Schroders communications, strategies or funds. This material is intended to be for information purposes only and is not intended as promotional material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. It is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this document when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of an investment can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed. All investments involve risks including the risk of possible loss of principal. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Some information quoted was obtained from external sources we consider to be reliable. No responsibility can be accepted for errors of fact obtained from third parties, and this data may change with market conditions. This does not exclude any duty or liability that Schroders has to its customers under any regulatory system. Regions/ sectors shown for illustrative purposes only and should not be viewed as a recommendation to buy/sell. The opinions in this material include some forecasted views. We believe we are basing our expectations and beliefs on reasonable assumptions within the bounds of what we currently know. However, there is no guarantee than any forecasts or opinions will be realised. These views and opinions may change. To the extent that you are in North America, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management North America Inc., an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Schroders plc and SEC registered adviser providing asset management products and services to clients in the US and Canada. For all other users, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.