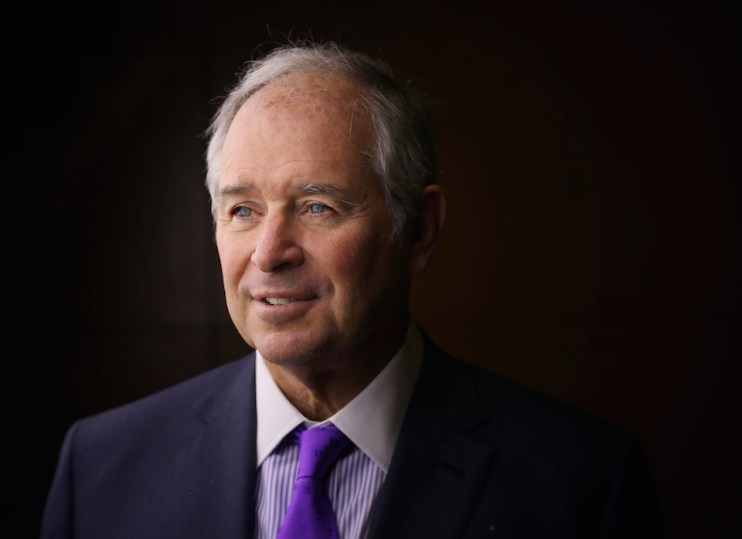

Takeover titan and Blackstone boss Steve Schwarzman talks charity, business and life advice

Private equity does not have a reputation for giving away money: on the contrary, it is an industry known for its hard-headed obsession with turning a profit though buying companies and selling them on.

So it comes as something of a surprise to find that the boss of the world’s biggest private equity company, Steve Schwarzman of Blackstone, is also one of the world’s biggest philanthropists.

Read more: Trio win economics nobel prize for work on poverty

The Wall Street veteran, now 72, has made a swathe of mega-donations in recent years including $100m to the New York Public Library, $100m to establish a scholarship programme for Chinese students, $150m to Yale University, $350m to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and most recently, a £150m gift to Oxford University which the institution said was its biggest donation “since the renaissance”.

Yet Schwarzman, whose guiding business principle is “never lose money”, sees no contradiction between his firm’s relentless pursuit of profit and his own habit of giving plenty of it away.

Sitting in his London office, on a tour to promote a new book, he stresses he does not fit the usual idea of a philanthropist as a rich man simply seeking to unload his cash.

“What you’re trying to do is create something that will really address societal problems,” he says. “The definition of the solution is the most important thing. It’s not the conventional concept of philanthropy where there’s some affluent person looking to get rid of money. The money comes at the end.

“I find I get involved in everything I do, sometimes for ten years or more. I end up with very large commitments.”

There is the strong sense that, for Schwarzman, philanthropy is less about giving and more about working; he relishes his crammed lifestyle of business and charity (and advising heads of state from time to time, including President Trump, whose Strategic and Policy Forum he chaired).

He greatly enjoys everything he does, he says – although writing his new book was an exception. “I hated it. I find writing a real struggle, because every word has to be precisely chosen, every sentence has to have the right structure. You can’t keep correcting yourself as you’re talking, like you can in a video.”

Read more: Climate activists target bankers during second week of protests

The book, What It Takes, an autobiography-cum-business self-help guide, details his rise from modest beginnings in Philadelphia to the top of the financial world. From an early age Schwarzman was ambitious, urging his father to expand his curtains and linens store across the state (to no avail – it seems his dad was happy with the status quo).

He went on to study at Yale and Harvard Business School, after which he joined Lehman Brothers where he quickly rose to prominence as the firm’s young star of mergers and acquisitions.

But even being the top dealmaker at an investment banking giant was not enough for Schwarzman’s appetite, so he founded Blackstone with former Lehman chairman Pete Peterson in 1985.

Through snapping up struggling firms on the cheap and offloading them several years down the line for a whopping profit, the company has built up nearly $550bn in assets under management. His own fortune is variously estimated at anything from $12bn to $18bn.

On the morning we meet, he has already been up since 4.30am, having just landed from the South of France to cram in a day of book-promoting media interviews before heading over to Washington. But he is showing no sign of fatigue; indeed, his hectic schedule seems to reflect his seemingly boundless energy, remarkable for a man in his eighth decade.

However, he is cautious in his comments.

A few days before we meet, Democrat presidential candidate Bernie Sanders has said he wants to abolish billionaires.

Does Schwarzman agree with the policy?

“Not particularly” he replies with a wry smile.

It’s about as political as Schwarzman will get.

Having once likened President Obama’s tax rises to Adolf Hitler’s invasion of Poland, the dealmaker is wary of putting his foot in the wrong place and won’t talk about Trump.

Like many observers of the financial markets, Schwarzman sees a global slowdown but does not think the major powerhouses across the world will all enter into recession.

He thinks that Europe’s struggling economies could bear the brunt of negative growth.

“There is a chance that Europe could be in recession and the UK, depending on what happens with Brexit.”

He is particularly perplexed by the downward push in interest rates across Europe.

“I don’t even understand what a negative interest rate is,” he says.

“I was thinking the other day – what would I do with a lot of money? Would I give it to somebody and let them charge me for giving them they money or just buy a warehouse, get a bunch of security guards and just leave it there?”

At the end of his book, Schwarzman gives a series of tips or rules for business, two of the most prominent of which are “don’t lose money” and “failure is the best teacher”.

I ask him how they square up – how can Blackstone employees, for example, learn from failure without losing a packet?

He insists they can, because everything that is done in his company is reviewed each week by the people at the top, and potential failures can be spotted early on.

“You don’t have to experience loss personally,” he says, “to be indoctrinated to the realisation that bad things can happen.”

And with that, he’s off for more interviews.