Sunak’s budget must navigate the Catch-22 of inflation and recovery

There have been some pretty bleak backdrops to budget announcements over the years. In March 2008, Alistair Darling faced the daunting task of delivering a budget while the world was in the teeth of the financial crisis.

Denis Healy’s April 1979 budget was surely the worst, after the government lost a vote of confidence. The flowers had only just begun to bloom after the original winter of discontent and Healey could deliver nothing more than a “caretaker budget” while Labour stared down the barrel of a doomed election.

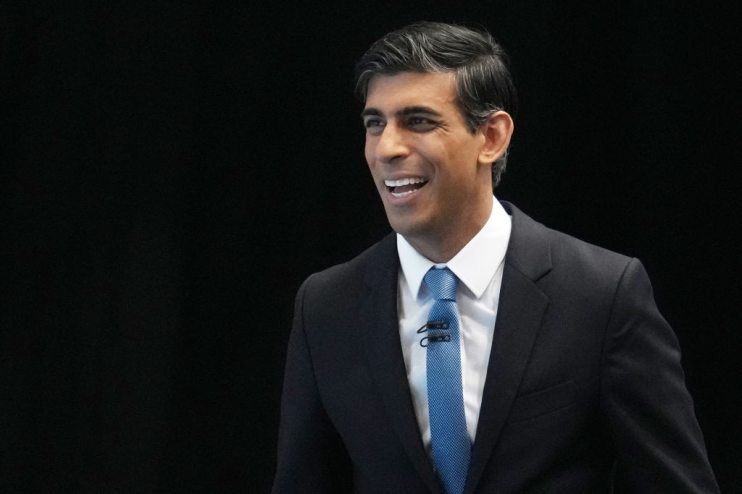

This one is pretty bad too, and the economic fallout risks dwarfing Rishi Sunak’s announcements next Wednesday if it gets worse.

The source of scorn directed at Healy (less so Darling) before his placeholder budget was inflation. The Chancellor faces a similar threat.

Although inflation edged back in September, experts think this is just the calm before the storm. And once that storm starts raging, it will be difficult to tame.

First, the numbers: there is greater tension within the government’s books due to a larger proportion of its debt pile being linked to the retail price index (RPI). This is short-dated debt, meaning the public finances are more exposed to interest rate hikes and whipsawing inflation.

With each additional interest rate percentage hike, the government’s interest bill could swell by around £10bn. The Treasury fears this could be closer to £25bn.

Inflation could average 4.6 per cent this year and four per cent next year, meaning the independent fiscal watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility, will have to hike its forecasts for interest payments by £14bn this year and £11bn next year.

The upshot of this dilemma is that Sunak is in a Catch-22 between monetary and fiscal policy. Both outcomes will impact his envelope.

He does not want price rises to spiral out of control as that will generate a jump in interest payments on existing inflation-linked debt. However, he does not want the Bank of England to hike interest rates as that will increase the cost of future borrowing.

With the prospect of interest rates rising sooner than many expected, the Chancellor does have ammunition to block his fellow cabinet ministers’ request for bigger packages.

But, economies and tax revenues are often in a stronger position when rates rise, so the higher debt servicing bill should not be viewed through one lense. Perhaps shielding the government from the vagaries of interest rates and inflation is precisely why Sunak will commit to stop borrowing to finance day-to-day spending next Wednesday.

For real people, importance of inflation’s impact is on households’ living standards, not on bean counters’ analysis. The cost of living crisis is biting hard. Supply chain breakdowns, compounded by the pandemic engineering a shakeup of normal buying habits, have raised prices.

With tax hikes looming, the squeeze will tighten further.

Households are having to make ends meet in a world where essential goods are more expensive and their income is unchanged. Rationally, they should demand higher wages, particularly if they expect prices to rise even more in the future.

This is the gamble Downing Street is playing.

Whether businesses can afford to pay higher wages without hiking prices is up for debate, and one the government seems hellbent on winning.

But if discontent continues to grow among the public, inflation will quickly spiral from economists wringing their hands in the bowels of Whitehall or the Bank of England, and will become an issue which could come to characterise Johnson’s premiership.

Sunak’s first budget was delivered as the country hurtled towards a lockdown. Last year’s spending review was limited to one year as we anxiously watched to see if the vaccine rollout could save us, and earlier this year, we were just about to crawl out from the winter lockdown.

In times of economic crisis, Chancellors are unable to exercise real discernible influence over the direction of the economy.

One exception to this rule was, in typical 2020 style, not a budget, but a financial statement in late March last year. The furlough scheme was a once-in-a-generation announcement which introduced the biggest state intervention in peacetime.

The ongoing fallout of the crisis has scuppered plans for our recovery. Next Wednesday’s budget is one that Sunak hoped would be the moment he moves out of the shadow of the pandemic. He seems destined to stay shrouded for a little while yet.