Sunak and Starmer offer little new year cheer on ailing UK growth path

This brand new weekly column, published every Tuesday, will drill down into the stories behind the numbers to reveal what makes the UK – and global – economy tick.

But, today, inspired by what resembled soon-to-broken new year’s resolutions by political leaders last week, it will make the case for why a stable government economic strategy needs to be established to prevent another decade of lost growth.

Last week illustrated how an incumbent leader (Rishi Sunak) can be bogged down by a flailing economy, handing their pretender, in this case Keir Starmer, an advantage.

Sunak’s speech was a sombre assessment of Britain’s woes.

Listing off strikes, enormous NHS waiting lists and high inflation, he pinpointed the headwinds buffeting the economy.

The speech’s tone was initially glum before becoming repentant. For all his honesty on Britain’s economic plight, Sunak, as a leader, won’t wash with the public if they still feel markedly worse off by the end of 2023.

The Conservatives have made it clear they are unwilling to let the money flow any time soon.

And so did Labour chief Starmer in his first speech of 2023. The government “cheque book” will be back in the drawer if Labour wins the next election, he promised.

His remarks were aspirational and used the years of economic sluggishness as bait to ask whether Britons feel better off after more than a decade of Tory rule.

What united Sunak and Starmer was a lack of policy to grasp the nettle of the country’s decline.

Sunak wants young people to study maths until 18, but what’s more urgently needed is for the Prime Minister to show his workings on how to get the economy growing again.

Starmer wants people to believe Labour is now a party of sound finances. Does that mean more spending cuts or tax rises?

It’s worth setting out the scale of the problem facing Britain to illustrate why we have to avoid a repeat of the malaise we’ve been stuck in since the financial crisis.

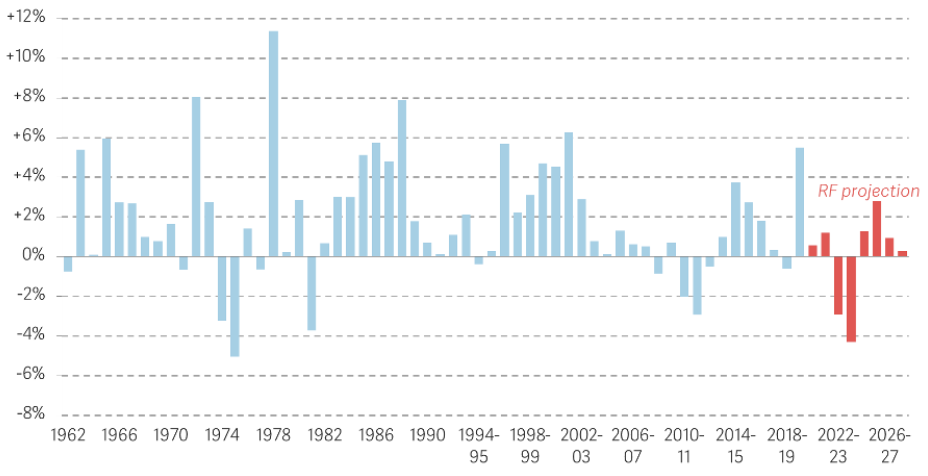

According to the Resolution Foundation, real incomes will not recover to their pre-pandemic levels until 2028 and over the next two years, some £2,100 will be swiped from Brits’ pockets by inflation (see graph).

Real incomes are in for a torrid time…

This is not the fault of Liz Truss scrapping the top rate of income tax or Boris Johnson hiking national insurance on a random day in September in 2021.

It’s a function of awful economic growth for more than a decade. Andy Haldane, former chief economist at the Bank of England, dismissed the government as having no blueprint to revive UK growth over the weekend.

Robust annual GDP growth should improve living standards over time. It should spur international investors to inject cash into an economy. It should strengthen households’ resilience to economic shocks. These are all things that Britain is now left wanting.

It seems policymakers will choose from two options to try to turn Britain’s fortunes around.

A return to David Cameron and George Osborne’s book balancing: the Sunak route.

Closer partnership between the state and private business: what Starmer hinted at.

Any leader that picks one and sticks to it for more than a year would be welcomed with open arms.

Sunak’s inflation promise

He said it will fall as a result of the plans the government’s have put in place. That’s a bit harsh on the Bank, who in December 2021 became the first major central bank to raise interest rates.

We’re quick to blame governor Andrew Bailey when inflation takes off. Maybe we should give him some credit when it cools, as it’s expected to (see graph).

… but inflation is on a downward path

You might have missed

People have grumbled at the Bank of England jacking up interest rates, mainly because it seems counterintuitive to do so when the UK economy is wilting. But it’s a necessary response to a slowdown sparked by high inflation. 2023 will see the effects of higher rates surface. The ONS said yesterday nearly 800,000 mortgagors’ bills will double this year, eating up money that could’ve been spent down the pub or on the high street.

Are we in a recession?

You’d be forgiven for thinking the UK is already in a recession. But, officially, we’re actually not. An economy is said to be in a technical slump when it suffers two consecutive quarters of contraction. Latest figures show GDP fell 0.3 per cent in the three months to September. The ONS is likely to confirm the recession on 10 February.

Send us your thoughts on Sunak and Starmer’s plans

What steps do you think the leaders should table to revive the UK economy? Email jack.barnett@cityam.com