Striking a chord: How music rights firms serenaded the stock market

Anyone who has the misfortune to monitor news updates on the London Stock Exchange will know the name Hipgnosis.

Less than a month into 2021, the gauchely-named company has already issued nine wordy announcements. They are not, however, the usual trading updates or dry regulatory disclosures. Instead, Hipgnosis has been on a relentless acquisition spree that has seen it splurge £1.5bn buying up the rights to songs by artists from Michael Buble to the Wu-Tang Clan.

Hipgnosis is not alone. In November, New York-based Round Hill listed its songs fund in London, raising $282m (£212m). In the US, Universal and private equity giant KKR are also getting in on the act. As artists and songwriters line up to flog their catalogues, and investors wise up to the potential takings from their favourite tunes, a musical arms race is now under way.

Banking on beats

The proposition is straightforward. Music rights firms buy up song catalogues and look to generate additional royalties through streaming and by placing tracks in films, TV shows, adverts and video games. Hipgnosis, which listed in London in 2018 and has already risen into the FTSE 250, has led the way in establishing music rights as an asset class.

Boss Merck Mercuriadis describes songs as a recession-proof asset much like gold or oil, immune to wider economic fluctuations. This, he says, has been demonstrated by the sector’s strong performance throughout the pandemic. After all, no health crisis is big enough to stop people from listening to music.

Music rights are also high yield. Round Hill has said it is targeting annual returns of between nine and 11 per cent through its investment in music intellectual property. Alice Enders, director of research at Enders Analysis, describes music publishing as “bond equivalent”. For artists and songwriters, catalogue sales offer the chance to cash in on their lucrative intellectual property. A sale can bring an artist 15 years’ worth of income in one fell swoop, says Mercuriadis — even more if the proceeds are booked as capital gains rather than income.

‘A perfect storm’

If music rights sales have been picking up pace in recent years, they have now broken into a sprint. One popular theory is that the outbreak of Covid-19 and the resulting collapse in touring has forced asset-rich artists to cash in their chips. Yet most recent catalogue acquisitions have come from non-touring artists who are more likely to be thinking of estate planning than sold-out gigs.

Fundamentally, the investment class has been fuelled by the rise in streaming, which has dragged the music industry up from its near collapse as a result of rampant piracy at the beginning of the millennium. “The value of music rights has definitely gone up because of the opportunity that streaming represents,” says Enders.

Now, with Hipgnosis’ spending spree pushing up prices and interest rates at historic lows, investors are pouncing. “It’s a perfect storm,” says Round Hill chief executive Josh Gruss. “If we don’t jump in here we’re not going to have these opportunities again.”

Who’s flogged their hits?

- Neil Young — sale of 50 per cent stake in the Canadian rock ‘n roll star’s portfolio of 1,180 tracks to Hipgnosis

- Bob Dylan — entire catalogue, including Blowin’ In The Wind, The Times They Are a-Changin’, and Like A Rolling Stone, sold to Universal Music

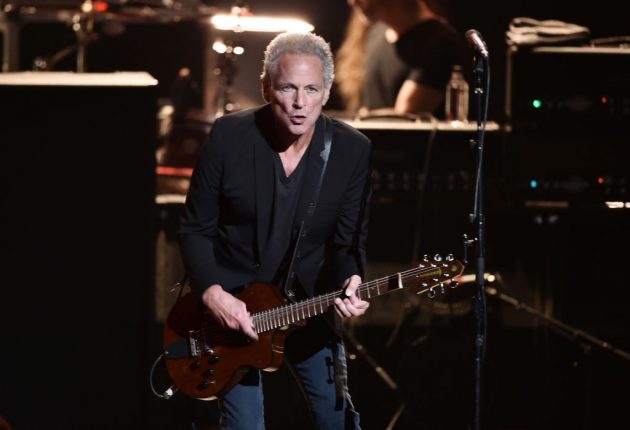

- Lindsey Buckingham — sale of Fleetwood Mac tracks such as Go Your Own Way and The Chain to Hipgnosis

- Take That — sale of tracks by producer Ian Levine from 1992 album Take That & Party to One Media IP

- Shakira — entire catalogue, including Hips Don’t Lie and 2010 World Cup anthem Waka Waka, to Hipgnosis.

Music rights rivals

With a finite number of classic catalogues out there, Hipgnosis and Round Hill are now going head to head to snap up the best assets for their London investors.

The two companies have their differences. While Hipgnosis is focused on securing a small number of high-profile artists, Round Hill, which is the seventh largest music company in the US, is playing a scale game. Moreover, Round Hill plans to grow its London listing partly by buying in assets from its existing private equity funds. This, the firm says, means it does not necessarily need to compete for acquisitions in the open market.

For the US giant, the success of Hipgnosis also helped pave the way for its listing. “Hipgnosis made things so much easier for us, because it took a lot of risk out of the process knowing that they had already educated all the investors about the space,” says Gruss.

Nevertheless, there is a respectful rivalry between the companies as they jostle for prominence in the market. Hipgnosis’ proposition relies heavily on the industry connections of boss Mercuriadis, who has managed artists including Nile Rogers and Beyonce. Round Hill, by contrast, is keen to stress its financial credentials.

“I know Merck likes to tout his connectivity but it’s just him, it’s just one guy, and there are plenty of deals that he’s been nowhere around,” says Round Hill president Neil Gillis.

Mercuriadis insists that Hipgnosis can secure catalogues even when Round Hill has offered more money. “We certainly welcome the competition, but I don’t worry about them,” he says.

Under the spotlight

Mercuriadis may have another reason to worry, however. Amid a flurry of recent acquisitions, Hipgnosis is now being subjected to close scrutiny by market watchers. In a note published earlier this month, Numis raised concerns about the lack of financial details in its acquisition announcements. Meanwhile, analysts at Stifel have raised questions over a number of valuation “bumps” in music catalogues shortly after Hipgnosis has acquired them.

Massarky, the independent valuer to Hipgnosis, has issued a strongly-worded riposte to Stifel’s “mistaken” analysis, insisting it used “transparent, specific, and granular techniques” to provide an objective valuation.

But uncertainties around this nascent asset class will likely linger for many investors. The opacity of catalogue valuations and infrequency of transactions has invited comparisons to the inflated price tags given to the highly illiquid assets in Neil Woodford’s doomed fund.

Media analyst Enders suggests the scrutiny of Hipgnosis may be the market “sizing up a small player”, adding that Universal did not face questions over its valuation techniques.

However, she says transparency over financial disclosures is key in a relatively unfamiliar business such as music rights. “I would say transparency is probably going to be a differentiator between Round Hill and Hipgnosis,” she says.

To succeed under the public gaze of the stock market and soothe investor jitters, therefore, both companies will need to marry their artist nous with a solid financial proposition.

“There’s an element of maths to it, but then there is an element of art to it,” says Round Hill’s Gillis. “That’s why the combination of the music people and the finance people coming together is vitally important.”