Starmer urged to build more homes in big cities and forge closer ties with EU to boost growth

The government has “much more to do” if it wants to have the strongest economic growth rate in the G7, according to the Resolution Foundation.

Since entering office, the new government has announced a number of measures to try and boost the economy’s productive potential, including an overhaul of the planning regime and plans to increase public investment.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer has stressed that growth is his “number one priority” while Chancellor Rachel Reeves has pledged to lead the most “pro-growth” Treasury in history.

But in a new report assessing the impact of the government’s economic reforms, the think tank argued that Labour needed to be bolder in a range of other areas to come close to meeting its ambitious growth target.

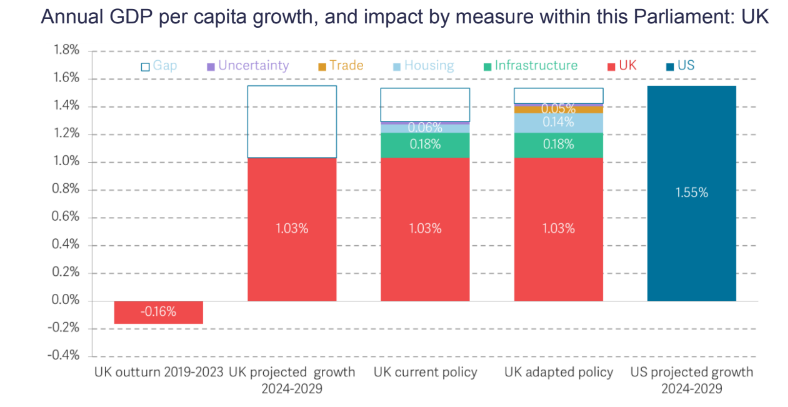

It modelled the likely impact on growth if Labour successfully met its ambitious housebuilding target, finding that it would provide a 0.06 per cent annual increase to projected per capita growth rates.

However, the think tank pointed out that the government’s new targets are too focused on smaller areas rather than major cities, where the potential growth boost is greatest.

Under the government’s existing targets, the Resolution Foundation estimated the housing stock would rise 1.4 per cent in towns and villages as opposed to 1.2 per cent in major cities like Manchester and Birmingham.

“Reorienting the targets towards highly productivity areas and cities could feasibly boost annual growth by up to 0.14 per cent,” it said.

The government has also announced a range of measures to help boost both public and private spending on infrastructure. This will come thanks to planning reforms and the creation of a National Wealth Fund, which will seek to crowd in £3 of private sector investment for every £1 it spends.

These measures could boost annual growth by up to 0.2 percentage points over the next decade.

While these policies form a “good start,” it still leaves the UK a long way short of the per capita growth rates forecast in the US over the next five years.

To close the gap further, the government should aim for a “much more ambitious plan on broad regulatory alignment with the EU,” which could boost GDP-per-capita by 0.6 per cent over the next ten years.

This would not mean the UK was re-entering the single market or the customs union, but would reduce barriers to trade, particularly for goods exporters.

Goods trade has suffered especially badly since Brexit, growing at a much slower rate than the rest of the G7. According to the OBR, UK goods trade was around 10 per cent below 2019 levels at the end of 2023 whereas it was around five per cent higher on average across the rest of the G7.

“A trade reset with the EU could ease some of the damage evident from Brexit,” the think tank said.

More fundamentally, the Resolution Foundation urged the government to develop a coherent growth strategy. “Such a strategy is essential to help the Government to understand the scale of the task it faces, and to resolve the tradeoffs that exist between its full set of policy instruments and policy objectives”.

A report from the OBR last week made clear the potential fiscal benefits of generating economic growth.

The report warned that public debt was on course to rise to 270 per cent of GDP by the mid-2070s on current trends, but if productivity growth returned to its pre-financial crisis average then debt would remain below 100 per cent of GDP for the entire forecast period.