Sports must protect its precious human capital like Djokovic and Hamilton

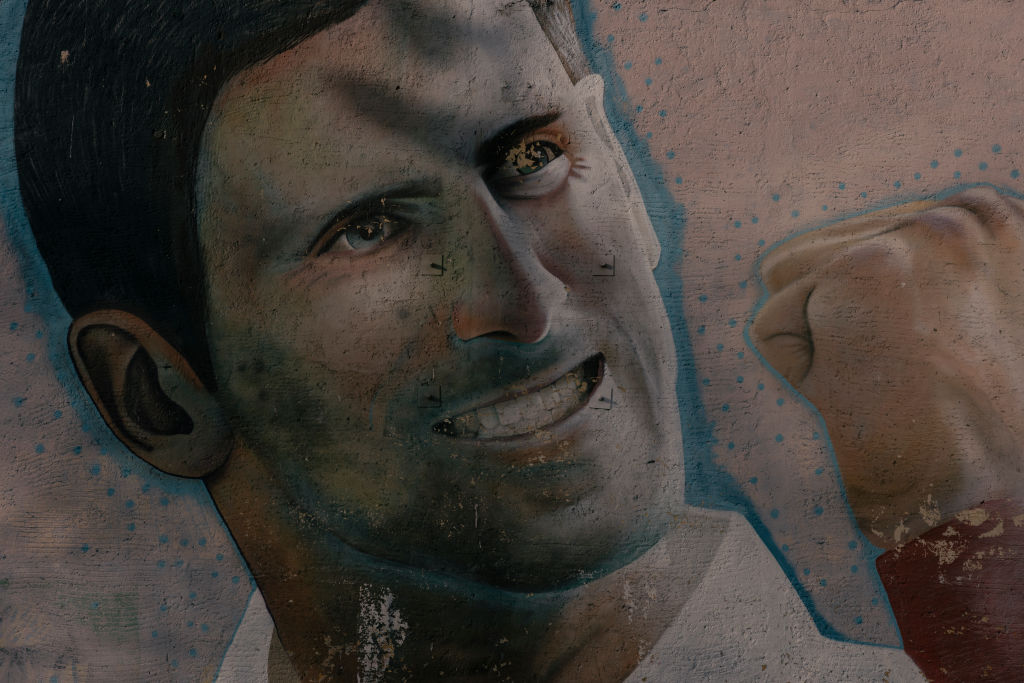

Picture Novak Djokovic. Do you see a villain sticking two fingers up at vaccine orthodoxy, or a heroic advocate for personal freedoms you’d risk a pepper-spraying for?

What of Lewis Hamilton and his rainbow helmet and sloganed T-shirts? Gesture politician or vital diversity campaigner? And what say you as one football team takes the knee while its opponents stand and their fans jeer? Empty virtue signallers, perhaps? Or does it depend which of those two teams you support?

It’s in our DNA as sports fans to view athletes as public property, as fair game for vocal criticism. To take polarised positions on them. The lazy approach would be to see this as going with the territory of their stardom, especially in today’s social media age when celebrities hang their lives and opinions out online for us. And maybe that can never now be dialled down.

Where, though, lies the responsibility for helping sportspeople help themselves to navigate these turbulent waters of public opinion, in which tides are unpredictable, turning violently without apparent warning?

Djokovic may not have been traduced – he seems to have done that for himself – but he’s been badly let down by the tennis authorities. Will they now work to rehabilitate him, or is that too risky a challenge for the bureaucrats to grasp while they scramble to hold onto their own jobs?

What, too, of the duty of care to Hamilton? It’s reported that he wants to see the outcome of the inquiry into the debacle of the season-closing Abu Dhabi Grand Prix before deciding his future in the sport.

Whether he does or not, why should that inquiry take three months, not reporting until the eve of the new season? Even the probe into multiple lockdown drinks parties in Downing Street will be completed in a fraction of the time.

We may posture that we want to be able to treat our sporting gods like flies, to be swatted and squashed at our whim, but any sane lover of sport must also recognise the need for strong leaders who get the imperative to protect its precious human capital – including protecting it from itself.

The mantra that no one person is bigger than a sport is easy to trot out. Rafael Nadal did just that this week in expressing his frustration at the Djokovic deportation circus. And tennis, of course, is multi-starred, not at all reliant on one player. But Joni Mitchell’s adage that you don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone holds true.

Call my agent

No surprise that Djokovic threw his agent under the bus, blaming them for incorrectly completing his visa application. Goes with the territory.

Agency involves sucking it up, not just nailing down lucrative sponsorship deals. I remember one stellar athlete being wheeled on a luggage trolley around a 5* hotel lobby for the amusement of the reception staff while his agent, a sheaf of passports in hand, stood next to me at the desk sheepishly checking in his client and all their entourage. Still, 15 per cent can be a lucrative salve for a bruised ego.

Aide memoire: Hoddle managed England

The Serb tennis star may of course have cratered his commercial value over the past fortnight. At least he doesn’t have an employer to appease, and (Covid protocols permitting) can continue to chase prize money on the circuit.

His vaccine stance reminds me of the sudden conclusion to Glenn Hoddle’s England management after he revealed his belief in reincarnation, claiming disability was punishment for sins in a previous life.

Hoddle hadn’t led England’s footballers with distinction. He went on to manage three club sides, again without much success. But 23 years on, every time I hear his co-commentary on a game on TV, I can’t help but remember his self-destruction.

In the years ahead, Djokovic will likely find that memories of his deportation linger longer than those of his many Majors.

Keeping a KPI on the ECB

The Digital, Culture, Media and Sport select committee report into racism in cricket is a flimsy affair. But at least for once the MPs have got a wiggle on and published their findings promptly. Can’t have it both ways I guess.

The sting in a meagre three pages is the insistence that the ECB report to the committee every three months on its work to root out institutional racism.

Which begs the immediate questions: are these politicians qualified to agree and then monitor a meaningful set of KPIs, and isn’t this anyway Sport England’s job?

This could be the first political test for cyclist Chris Boardman, who has kept a surprisingly subterranean profile since becoming Sport England’s chair back in June. Do the MPs not trust the funding agency to monitor the fitness of cricket’s governing body to be in receipt of lottery and exchequer funding – something it does day-to-day across a wide range of organisations?

The quango’s chief executive issued a bland statement hours after the DCMS report was released. Its eloquence lay in what was not said rather than what was. No acknowledgement of the MPs’ demand for their own ECB reporting line.

Any bets on how many of the quarterly reports are issued before they are quietly dropped?

Start making sense

Baffled by conflicting analyses of England’s wretched Ashes performance? Try reading Hitting Against the Spin: How Cricket Really Works by analysts Nathan Leamon and Ben Jones. Simple game, really. It’s the execution of it that’s so difficult.

Ed Warner is chair of GB Wheelchair Rugby and writes at sportinc.substack.com.