The spectre of entrenched inflation will soon hit loss-making start-ups hard

Larry Summers was Treasury Secretary to Bill Clinton, Barack Obama’s Director of the National Economic Council, and President of Harvard University. When he offers an economic prediction, therefore, he is worth listening to. A recent one was sobering. Summers believes we are entering a period of “higher entrenched inflation”.

Make no mistake: inflation is a menace. To Ronald Reagan, it was as “violent as a mugger”. To John Maynard Keynes, it was a “confiscation” of wealth. Lenin considered it, rather gleefully, a “millstone” with which to ”crush the bourgeoisie”.

At its worst, inflation has the nasty habit of creating its own momentum. Businesses raise their prices and employers demand higher wages, and so the expectation of inflation becomes its own cause. Run riot, as in Weimar Germany or Mugabe’s Zimbabwe, bank notes end up worth less than the paper they are printed on.

We are far from the terrors of that kind of hyper-inflation today. Yet inflation is at its highest level in many years. Britain’s inflation rate has just reached a thirty year peak, and America’s hasn’t been this high since 1982.

Inflation hits everyone, eroding all savings – there’s a reason Lenin loved it. But those who should be most concerned are those who have relied most on the recent years of stable, low-inflation.

One such group are the loss-making start-ups whose frothy valuations have been predicated on the hope of a brighter, more profitable future.

In an era of low interest rates and an excess of investor cash, money has flown into high-risk investments like these, with venture capitalists falling over each other to bet on the next big thing. In the last decade venture capital investment ballooned from $47.6bn in 2010 to a high of $322bn in 2018.

High inflation, however, is a likely cause of a nasty awakening.

To understand why, imagine, for a moment, that you are the Chief Executive of Bubble Inc. Today, your driverless, electric hoverboards are little more than a half-baked idea, but external investment has flooded in, with few questions asked.

Once inflation comes, a lot of things hit you at once. First, supply chain shocks – one of the immediate causes of today’s inflation – drive up your costs. Your employees, feeling the squeeze themselves, demand a pay rise too. You’re spending more money than ever.

The government, meanwhile, has taken action to reduce inflation by increasing interest rates, encouraging people to spend less, save more, and thus suppress demand.

This hits you in more ways than one. First, your customers stop spending. With credit expensive, and savings more appealing, your hoverboards start to look less tempting. Next, the borrowing that you rely on starts to come with a heftier interest rate than any you’ve paid before. Finally, the investors themselves start to seek safer returns elsewhere. The promise of your profitability, far off in the future, starts to look less promising than bonds with high interest rates or surging commodities.

Warren Buffett once said that, “only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.” For over a decade, loss-making companies have been afforded extraordinary valuations as investors went in search of the next Google, Facebook or Amazon.

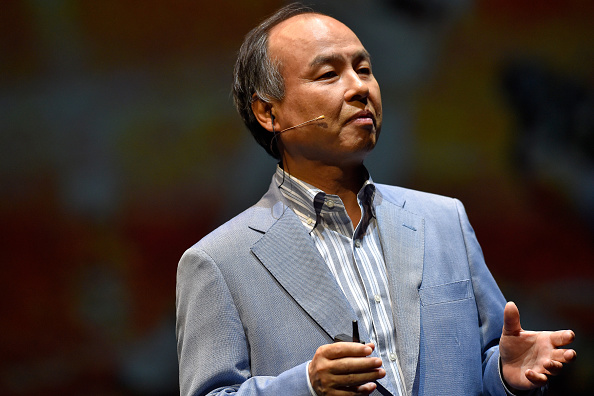

Inflation will change that. In fact, Buffett’s tide is already turning. Softbank, the investment group run by Masayoshi Son, is a useful canary in this coalmine. Son has an eagle eye for an overvalued tech stock, having funded some of the most extravagant blow-ups in recent business history, not least sinking $18.5bn into WeWork before ultimately valuing the company at a fraction of that. Notably, the combined value of Softbank’s investments is already falling, down $19bn in the past year.

Not all technology stocks will be found naked when the tide comes out. Those already turning a profit, with sufficient market power to increase their prices and hold on to their customers – think Apple, Alphabet, Amazon and Meta – will survive. This is not the end of big tech.

But the bubble that those companies inspired, spurred on by investors who wanted to be the first to the next big thing, has long been fit to burst. Inflation provides the pin.