Six strategies for your retirement income

What surprises me most about my wife’s catering business is how much food is usually left over. I often ask: ‘Is there a better way to manage food costs?’. Her answer is always the same: ‘Better to have food left over than fall short.’

She has the exceptional ability to estimate how much each person will eat but can never be sure how many people will come or their appetite.

When we are helping our clients plan for retirement, we don’t know how much they will need either. But we never want them to fall short. To make sure they have enough, we must help them account for numerous factors. These include:

- How much income will they need?

- How long will they need it?

- What will inflation look like?

- How much will they want to leave to their beneficiaries?

Answering these questions can be daunting and is, by nature, inexact. Assorted financial applications attempt to model the various scenarios. But no matter how precisely our clients anticipate their needs, the sequence of investment returns will never be certain. And that is one of the most important factors in determining their retirement success.

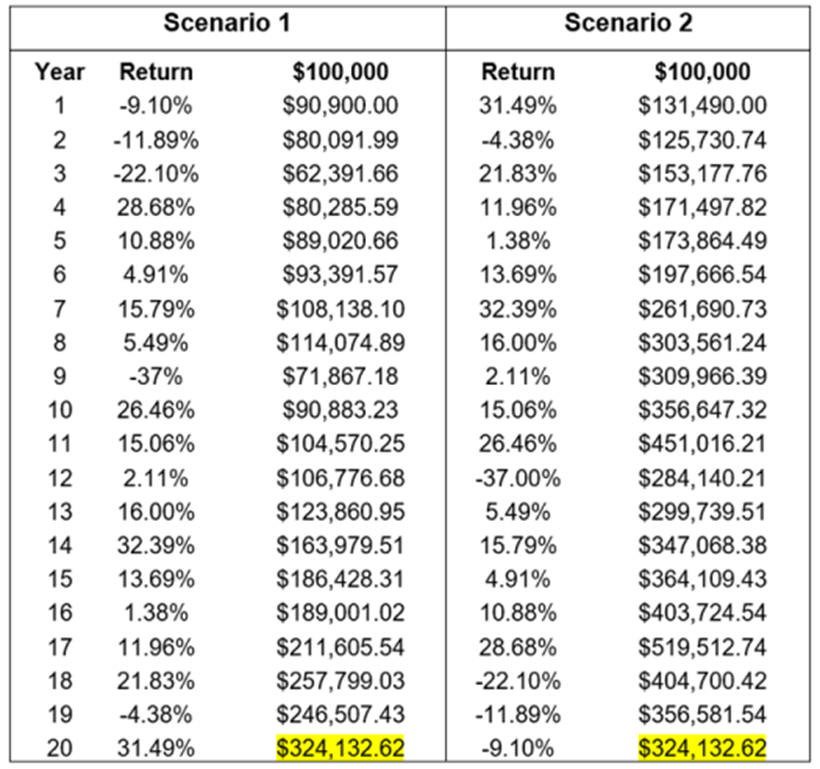

The sequence of returns is the order in which returns are realised, and as clients accumulate assets, it hardly matters. Let’s say a client starts out with $100,000 (about £76,000) invested in stocks. In Scenario 1 below, they experience negative returns at the beginning of their investment horizon, while in Scenario 2, the sequence is flipped and the negative returns come at the end of the horizon.

Regardless of the sequence, the end-value for the client is the same: the average return in both scenarios is 6.05%. But as clients enter retirement, they have to account for distributions. And that changes the maths.

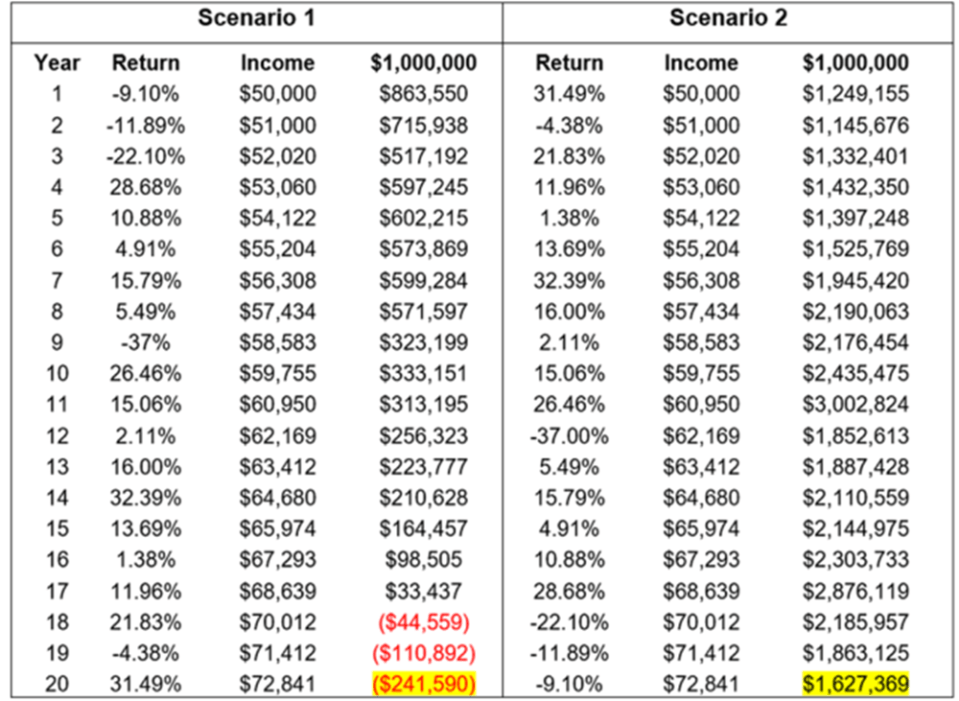

Using the same returns, they now have a real income distribution of $50,000 per year, with a two per cent annual inflation adjustment, from a starting nest egg of $1,000,000.

The ‘average’ return in both scenarios is the same, but now with vastly different outcomes. If the client encounters negative returns at the outset, as in Scenario 1, they run out of money – a disaster. But in Scenario 2, their capital grows to $1.6 million. Which begs the question: ‘Did they maximise income?’.

This situation reflects the sequence of returns risk (SoRR) in retirement. The lesson is simple: the order in which the returns are generated is more critical to success or failure than the average return. SoRR along with longevity risk and unexpected expenses are key factors in determining whether clients have enough money to fund their retirement.

To address these factors, various strategies have been developed. Generally, they fall into one of six categories, each with its own merits and shortcomings: Certainty, Static, Bucket, Variable, Dynamic and Insuring.

These strategies – which we run through in the remainder of this article (below) – are hardly exhaustive. We can never be sure of the sequence of returns, time horizon and biases that may derail a plan.

1. The Certainty Strategy

Many institutions employ asset-liability management (ALM) to fund their future liabilities. Simply speaking, clients invest money today in a manner designed to meet a future liability with a high degree of certainty. For example, let’s assume one year from now they want to cover $50,000 in income and the current interest rate environment is 3%. If the interest rate and principal are guaranteed, we might advise them to invest $48,545 (i.e. $50,000 divided by 1.03) today to meet that future obligation.

But this will not protect them from inflation.

For all its certainty, this strategy has some drawbacks. To ensure the client doesn’t run out of money, we’d need to determine how many years to fund, an almost impossible — and morbid — task.

2. The Static Strategy

If clients lack the capital to fund the ALM strategy or can’t estimate how long their retirement will last, an alternative approach is to determine a ‘safe’ portfolio withdrawal rate. Using historical returns on a 50/50 stock-bond portfolio, William P. Bengen calculated an optimal starting withdrawal rate of 4%. Therefore, to sustain a real annual income of $50,000, a client would need $1,250,000. Every year thereafter, they would adjust the previous year’s withdrawal for inflation.

Like any retirement income strategy, this involves several assumptions. Bengen estimated a 30-year retirement horizon and an annual rebalance back to the 50/50 portfolio. The key challenge for retirees is rebalancing back into stocks after a large drawdown. Such loss aversion-inspired tactics could derail the strategy.

While Bengen’s 4% withdrawal rate has been fairly effective, recent elevated stock market valuations and low bond yields have led Christine Benz and John Rekenthaler, among others, to revise that starting withdrawal rate downward.

3. The Bucket Strategy

This approach leverages mental accounting cognitive bias or our tendency to assign subjective values to different pools of money regardless of fungibility — think Christmas account. Clients establish two or more buckets: for example, a cash-like short-term bucket funded with two-to-three years of income need and a long-term diversified investment bucket with their remaining retirement funds.

In retirement, the client pulls their income needs, year to year, from the short-term bucket as its long-term counterpart replenishes those funds over specified intervals or balance thresholds.

This Bucket Strategy will not eliminate SoRR but it gives clients more flexibility to navigate market downturns. Bear markets often compel retirees to rebalance to more conservative allocations as a means of risk mitigation. But this reduces the likelihood that the losses will be recovered or future income increased.

By separating the buckets, clients may be less prone to irrational decisions, secure in the understanding that their current income will not be affected by market downturns and that there is time to replenish the funds in the long-term bucket.

4. The Variable Strategy

Most static retirement income programmes simply adjust a client’s income distribution for inflation, keeping their real income the same regardless of need. But what if their income needs change?

Analysis by Morningstar’s David Blanchett, CFA, found that spending doesn’t stay the same throughout retirement. He identified a common ‘retirement spending smile’ pattern: clients spend more early in their retirement, taper their expenditures in middle retirement and then increase their outlay later in retirement.

With this in mind, clients may wish to deploy a variable spending schedule that anticipates the ‘smile’. This will yield higher initial income but may have to overcome certain behavioural biases to succeed. We tend to be creatures of habit and it’s hard for us to adjust our spending patterns in response to lower income. Moreover, the models aren’t clear about how much income reduction to plan for.

5. The Dynamic Strategy

While a variable income strategy lays out phases to income, a Dynamic Strategy adjusts according to market conditions. One form of dynamic income planning uses Monte Carlo simulations of possible capital market scenarios to determine the probability of a distribution’s success. Clients can then adjust their income based on the probability levels.

For example, if 85% is deemed an acceptable success threshold and the Monte Carlo calculates 95% distribution success, the distribution could be increased. Alternatively, if the Monte Carlo simulates a 75% probability, distributions could be cut. A 100% success rate is ideal, obviously, but it may not be achievable. That’s why determining what level of confidence suits the client is an important question. Once that’s decided, we can run the Monte Carlo at pre-defined intervals — annually, bi-annually, etc. — to increase or decrease income. As with the variable income option, this assumes a client can and will moderate their spending both up and down.

6. The Insuring Strategy

Most of the strategies thus far assume a retirement horizon. But that horizon is impossible to predict. The only way to eliminate a client’s longevity risk is to insure the retirement income stream. In this scenario, the client works with an insurance company, paying a lump sum up front to guarantee a regular income over a single or joint lifetime.

To evaluate the strategy, we must balance the comfort of receiving an income regardless of market performance or longevity against the potential costs. Principal accessibility, beneficiary payouts, creditworthiness and expenses are just a few factors to consider.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

By Krisna Patel, CFA, is owner/operator of The UnBiased Advisor located in Broomfield, Colorado. He has spent over 19 years in the financial planning field, after graduating from Indiana University with a degree in public finance.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Information presented herein is for discussion and illustrative purposes only and is not a recommendation or an offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities. Views expressed are as of 01/24/2022, based on the information available at that time, and may change based on market and other conditions. Although certain information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, we do not guarantee its accuracy, completeness or fairness. We have relied upon and assumed without independent verification, the accuracy and completeness of all information available from public sources.

Securities and investment advisory services offered through Woodbury Financial Services, Inc. (WFS), member FINRA/SIPC. WFS is separately owned and other entities and/or marketing names, products or services referenced here are independent of WFS.

Image credit: ©Getty Images / Strauss/Curtis