Should football brace itself for a dementia claims crisis?

Last week the Football Association’s head of medicine, Charlotte Cowie, announced the governing body was considering “likely risk factors” for dementia among players.

The review comes as concern grows across contact sports around the potential link between neurodegenerative disorders and head trauma. The concern isn’t new – Alan Shearer’s 2017 documentary Dementia, Football and Me provided a player’s view – but has become a hot topic.

The FA’s intention to investigate the issue further continues efforts to improve player welfare. A year ago, formal “heading guidance” was issued for all youth age groups and last weekend saw the introduction of concussion substitutions in the Premier League.

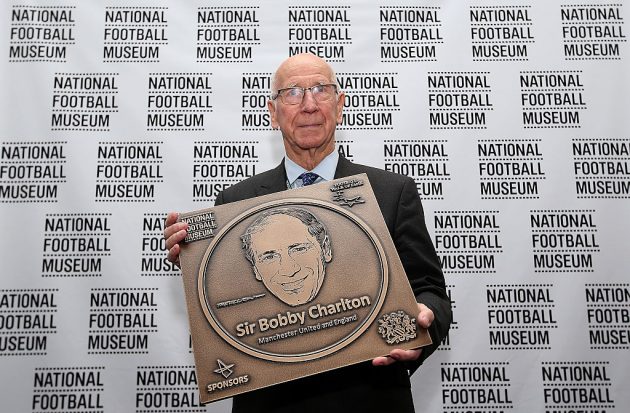

With a number of the game’s legends reported to have suffered some form of neurodegenerative disorder, including Bobby Charlton, Jackie Charlton and Nobby Stiles, there is inevitable concern about the impact on the game from the current elite players to the grass roots.

Rugby v Football: A different kind of debate

The usual comparison made between football and rugby is of the former being “a gentleman’s game played by hooligans” and the latter “a hooligans’ game played by gentlemen”.

Given its greater physicality, the protection of rugby players might be seen as a more urgent issue.

Late last year, eight former rugby internationals with dementia and similar neurodegenerative disorders, which they believe have been caused by the sport, announced they would be pursuing a claim against national and world governing bodies for failing to adequately protect them.

Does that mean football can expect similar claims?

Any conclusion that heading the ball causes dementia is far too simplistic, but there is a developing picture that it may not take a knock-out blow to cause trauma to the brain. Lower level “sub-concussions” may carry an increased risk of neurodegenerative disease.

In October 2020, an inquest into the death of former Everton and Wales footballer Alan Jarvis determined his career was a factor in his “declining neurodegenerative illness” leading to Alzheimer’s, and in the circumstances his diagnosis should be regarded as an industrial disease.

Played the game, make a claim?

Though there is no indication of claims in the pipeline, if any are intended they will face the same significant hurdles as those presented to the rugby union authorities. Established legal principles do not discriminate by the shape of the ball.

The extent of a club’s or governing body’s duty is not straightforward. Wider historic issues of player welfare, monitoring, enforcement, and state of knowledge all need to be considered.

As research develops, so does our understanding. We are better informed now than ever, but the picture is still not clear.

A recent publication from Imperial College observed “the link between the mechanical forces that act on the brain [during trauma] and the resulting long-term changes is poorly understood.”

Medical causation in this area of claims is a potential minefield. A player who has hardly headed the ball can be diagnosed with dementia, and a player whose career was renowned for heading may have no issues at all.

The classification of “declining neurodegenerative illness” as an industrial disease following a sporting career does create potential for compensation claims to be made.

The framework exists from industrial exposure, for example to asbestos and vibrating tools, but the prospect of sports-related claims adopting that process is not straightforward. There may be similar issues, but they are not the same.

Potential claimant footballers and their representatives may be waiting for the outcome of the rugby litigation before taking the first step.

The fallout for football

Regardless of the potential of claims, it is appropriate for the FA to review and address evidence around head trauma.

That process is evolutionary, and we might expect existing heading guidance and concussion protocols to develop further.

Applying age-related measures is sensible, as is improving the wider knowledge on player welfare, head injury, recovery and treatment.

The use of technology in sports could also reduce risk, with the use of virtual reality in training and recovery shown to be effective.

The potential for compensation claims cannot be – and given the work of the FA appears not to be – the driving force behind development and progress of player welfare.

David Spencer, is a partner and head of the BLM Sports Practice Group. He advises a number of sporting bodies and clubs on insurance, claims and risk regulations, and is an appointed panel solicitor for a number of national sporting and recreational associations.