Set sail for the 1700s: Why the shipping industry is returning to technology from the history books

As countries and companies try to curb their climate impact, many are turning to space-age solutions. But the shipping industry is poring through the history books for inspiration.

Sails are making a comeback as companies bid to drive down emissions and cut down on costs. But modern sails look very different from their ancestors.

Read more: Global banks are leading the charge to decarbonise shipping

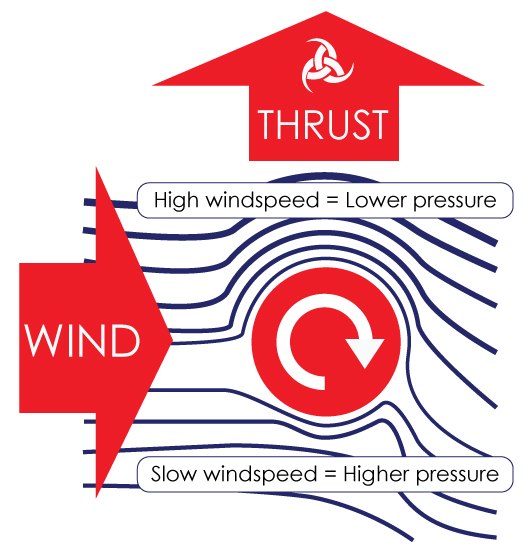

Finnish company Norsepower’s rotor sail is a metal cylinder which spins at high speed. It uses the same physics that allows Wimbledon stars to curve tennis balls to propel ships, spinning perpendicular to the direction of the wind (or tennis stars’ racquets).

Its designers reckon it can save 10 per cent on the cost of fuel, driving down emissions.

Another innovator is Louis Dreyfus, which hopes to mount kites to the front of container ships. This allows container ships to avoid sacrificing precious space on deck they need to store cargo.

Wartsila, one of the world’s top ship engine builders, this month announced a low-emission cargo ship which uses a sail positioned at the bow.

The new innovations let ships harness wind, a renewable source of energy, directly at source, rather than relying on wind farms.

“It’s a complete no-brainer – if you can make the technology work on your routes and your ship specification,” says Tristan Smith, an expert in low-carbon shipping at UCL.

International shipping is responsible for around two to three per cent of global emissions. But for a sector which, unlike cars, is unable to rely on electrification – batteries are simply too heavy and bulky for ships – sails can only form part of the solution.

Wartsila sees the future of the shipping industry ultimately lying elsewhere.

Andrea Morgante, the vice president in charge of business development, believes hydrogen or ammonia could become the dominant fuel for the sector in the coming decades.

However it will take around a decade for production to scale up, experts warn. In the meantime, Wartsila is putting its money on liquid natural gas (LNG), a fossil fuel with fewer pollutants than traditional methods.

“Our message is that we cannot wait for new technologies to become available to start changing,” Morgante said.

“We need to start having a serious conversation that [hydrogen and ammonia] are the only two options, and then get on with getting the investment in,” says UCL researcher Smith. He worries that switching to LNG could lock the industry on a path were it is burning fossil fuels well into the future.

By contrast, hydrogen and ammonia could create ships with no operating emissions.

The push to modernise fleets is gathering steam, and last week the government published its Clean Maritime Plan, which aims to make the UK a leader in the field.

The plan lays out a vision that all new ships being ordered for use in UK waters will by 2025 be “designed with zero emission propulsion capability”.

However, the plan merely sets aspirational goals and has few concrete policies.

The same can be said for new rules from the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), which last year set the industry on course to halve emissions by 2050.

Many big firms are falling behind on these targets, according to the CDP, an organisation which lobbies for environmental reporting from big companies.

“The sector can’t sail under the radar anymore,” says Carole Ferguson, the CDP’s head of investment research. “I think that people are looking at what they are doing,” she added.

These people include investors, and – perhaps more importantly – lenders.

Last month major banks, including Citi, Societe Generale and DNB, signed up to a new disclosure project.

The Poseidon Principles commit the banks to take climate change into account when lending to the shipping industry.

But this is not just about helping solve climate change. If regulation or technology runs away from ship owners, it could force them to scrap whole fleets, experts have warned.

And banks are not keen on the risk.

This week a study from analysts at Maritime Strategies International warned that whole fleets could be left stranded as demands shift in a decarbonising economy.

It projects that demand for oil tankers will fall by just under a third by 2045 as countries switch to other energy sources.

Read more: Shipping firm must pay £850,000 fine for bribes

The impact on the shipping industry “will go far beyond the impact of general market cycles”, says James Frew, who co-authored the report for MSI.

“Particularly for tankers, where we’re seeing demand destruction year on year, for 20 years. That’s going to make the tanker market a really tough place to be.”