Screenshot: Can cinemas bring Brits back to the big screen?

This week

**Media Moment of the Week: Every dog has its day

**Can cinemas bring Brits back to the big screen?

**Is Clubhouse really worth $4bn?

Media Moment of the Week: Every dog has its day

Doing a live piece to camera comes with risks, as any broadcast journalist will tell you. But one thing they don’t prepare you for on journalism courses is an encounter with an over-enthusiastic golden retriever who decides your microphone makes quite a good toy.

That’s what happened to this Russian reporter, who was left chasing the impertinent pup down the street. The dog eventually agreed to play ball and later joined the reporter to help finish off her live broadcast.

Can cinemas bring Brits back to the big screen?

What will it take to breathe life back into the cinema, I hear you ask. A three-hour Tarantino bloodfest? Perhaps a new arthouse classic from Bong Joon-ho? Well no, actually. What it takes, apparently, is a showdown between a giant reptilian monster and an enormous ape.

Since its release two weeks ago, Godzilla vs Kong has raked in more than $385m (£205m), attracting large audiences in the US and China despite limits on attendance. The masses want mindless escapism, it seems, and the latest instalment of the monster franchise is more than happy to deliver.

It’s also an encouraging sign for cinema operators in other markets. The impact of the pandemic on the industry hardly needs to be stated, with sustained closures during lockdowns compounded by the decision of some studios to delay film releases. London-listed Cineworld, the world’s second largest cinema chain, saw its revenue crash 80 per cent last year and swung to a $3bn loss. It has been forced to raise almost $1bn in fresh funding to help avoid collapse.

Cineworld, which also owns the upmarket Picturehouse chain as well as Regal cinemas in the US, is now gearing up for UK reopenings on 17 May. It’s bullish about attendance figures, expecting audiences at 60 per cent of 2019 levels in the first month. A survey by industry group Cinema First suggests initial demand will be lower, with 40 per cent of audiences planning to return to the big screen within the first few weeks. Still, these are not bad numbers. What’s more, there’s now a pipeline of films to help draw the public back, including blockbuster hits such as Fast & Furious 9 and Top Gun: Maverick. At some point we’re also expecting the new Bond film, but don’t hold your breath.

A new threat is emerging, though, from streaming services. As lockdowns hit last March, consumers flocked to on-demand platforms. Disney Plus subscriber numbers surged past 100m in just 16 months (it took Netflix a decade to reach that milestone) and the media titan has tried to cash in on this audience by releasing titles directly through its platform. Other studios such as Universal and Warner Bros have also experimented with digital releases, sparking fears that direct-to-streaming could be the death knell for cinemas.

In reality, however, this has hardly panned out. Theatrical releases still give a much bigger impact than an exclusive streaming launch. What’s more, while streaming is now very much the norm, many viewers will balk at the idea of paying additional fees for digital releases. Disney Plus subscribers may rightly question the logic of forking out £20 to watch Mulan on a small screen (on top of their £5.99 monthly fee) when a cinema ticket costs half that.

The future, then, is likely to be a combination of cinemas and streaming. Cineworld has inked a deal with Warner Bros to show its films from opening, giving it a 31-day window of exclusivity (extended to 45 days if films hit pre-agreed box office targets). It’s a major coup for the cinema chain, and a sign that the big screen will prevail. Other positive signs can be taken from China, Japan and Australia, where box office takings have bounced back strongly following lockdowns.

Before the pandemic hit, UK cinemas had been enjoying something of a renaissance. In 2019 box office takings hit £1.25bn, boosted in part by the rise of boutique chains such as Curzon and Everyman, which have helped to reinvent the big-screen experience through premium seating, food and drink offers. While the last year has battered the sector to within an inch of its life, cinemas should rightly be optimistic about a recovery, despite the looming threat from streaming. And if it takes a fight between a monster and an ape to get people back, so be it.

Is Clubhouse really worth $4bn?

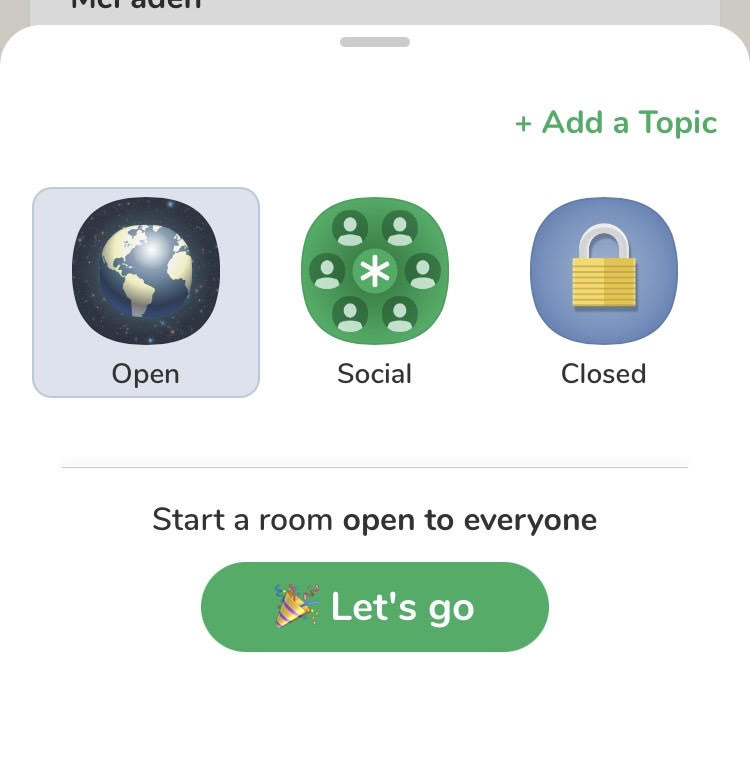

It’s been a big week for Clubhouse, the audio-based social media app that journalists insist on describing as “buzzy”. Bloomberg reported that the startup held talks with Twitter over a potential takeover deal valuing it at $4bn. After those discussions fell through, Clubhouse began exploring a fundraising round at the same valuation.

Launched just a year ago, Clubhouse has taken full advantage of the pandemic to become one of the hottest new apps. Its platform, which allows users to listen in to discussions and talks on a variety of topics, has proved popular among high-profile tech figures including Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg, while its invite-only launch strategy has added a gloss of exclusivity and further boosted its allure.

The eye-watering $4bn price tag has, however, raised some eyebrows. Despite its popularity (it’s thought to have around 10m users), Clubhouse is still very much in an initial trial stage and is yet to make any revenue. The app recently announced the launch of a payment system, allowing users to donate cash to their favourite speakers, suggesting it will follow the subscription model favoured by startups such as Patreon, Cameo and Only Fans. But — initially at least — it will not take any cut of these payments. Clubhouse, it seems, is in no rush to generate cash.

Yet there are still question marks about its long-term viability. Rival social media platforms, including Twitter, are building their own competitors to the service. Moreover, it’s not clear whether Clubhouse’s success will continue beyond the pandemic. While it’s hugely popular among tech folk, its wider relevance is unproven. What happens when it drops its invite-only model and Clubhouse ‘rooms’ are no longer the preserve of a social media elite? Or if celebrities (who draw the crowds) grow bored of the platform? This is not to mention the mammoth moderation problems emerging from the audio-based app.

Who knows if Clubhouse will succeed. The well-manicured paths of Silicon Valley are littered with the carcasses of short-lived fads (remember Houseparty??), but that doesn’t mean it is doomed. It has persevered for a year and, if it can manage its continued growth and path to monetisation right, it surely has a chance at success. But as investors continue to pour vast sums of money into nascent apps with zero revenue, it’s no wonder there’s talk of a tech bubble.

The algorithm recommends:

- Virgin Media boss Lutz Schuler has been named as the new chief executive of the firm’s £31bn joint venture with O2. Patricia Cobian, O2’s finance chief, will take the equivalent role but it’s farewell to Mark Evans, who’s led the mobile network for five years. All eyes on where he goes next…

- Cannes Lions has been cancelled for the second year running. The infamous advertising knees-up had optimistically plotted to go ahead as normal in the summer, but this week said it will be a virtual event instead.

- The UK has officially launched its new competition watchdog aimed at curbing the power of Big Tech. The Digital Markets Unit promises big things, but a backlog in legislation means it will likely be powerless for its first year…

Got a story? Drop me a line at james.warrington@cityam.com or on Twitter