Saudi Arabia’s attempt at a makeover is a global test to stoke liberalisation

How would Los Angeles influencers, decked out in their finest, go in the Saudi desert, instead of the usual hotspot of the Coachella Valley? This was one of the questions Edelman looked at when making their pitch to Saudi Arabia that they could help the nation reopen themselves to the world again. They surely need it: the Gulf kingdom, and its young crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, have been relegated to pariah status since the assassination of dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018.

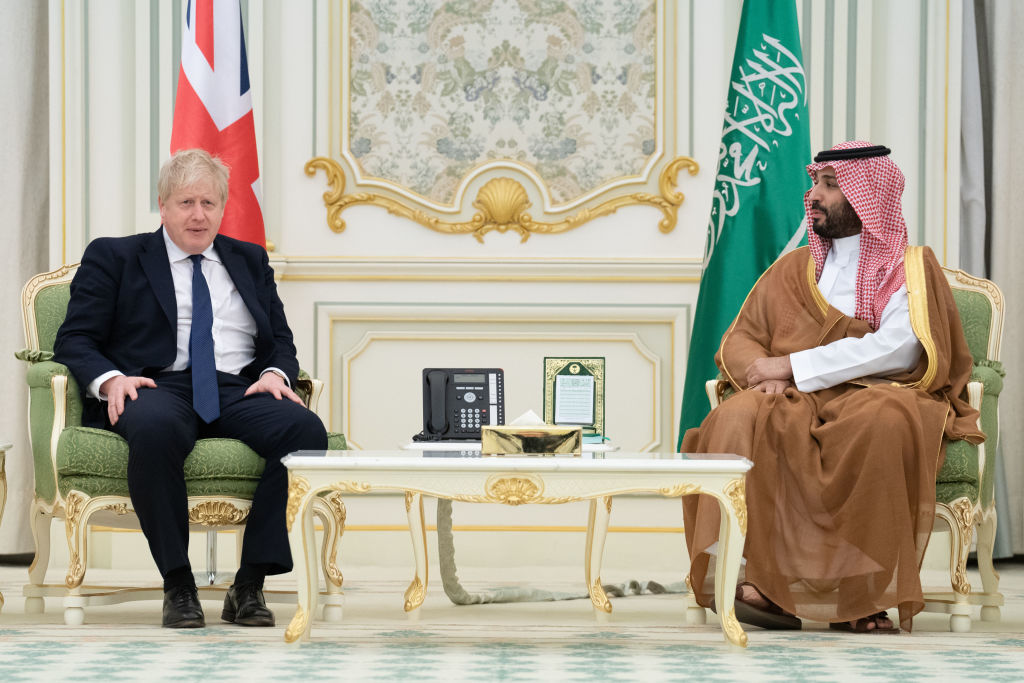

But the issue of relations with Saudi Arabia has been problematic for some time. Mohammed bin Salman was greeted as a liberalising force when he was appointed crown prince in 2017, and he had seemed like a figure with whom the West could do business. Saudi’s vast petrochemical wealth and strategic importance make it a critical ally in the Middle East as well as a potentially lucrative playground for private enterprise.

Edelman’s five year programme, said to be worth nearly $800,000 a year, would target the US, UK, France, Germany and the Kingdom’s Middle East neighbours.

This is a controversial move. PR firms of course like to draw analogies with lawyers, arguing that all clients deserve representation as a kind of natural justice; nor is it the first time Edelman has worked with Saudi Arabia, having signed a deal in 2020 to promote the new $500bn megacity Neom. But the crown prince remains unrepentant over his involvement in the Khashoggi affair, and a number of comms and lobbying firms cut their ties with Saudi in its wake.

The case against Saudi Arabia remains substantial. Khashoggi notwithstanding, there are still serious human rights concerns over the regime in Riyadh. Dissidents are regularly arrested and tortured, the crown prince maintains an assassination unit known as the Tiger Squad and Saudi Arabia continues a brutal war against Houthi insurgents in Yemen.

Yet Saudi remains a key ally of the West. It is the biggest importer of US military equipment in the world, the al Yamamah deal is the UK’s biggest ever export agreement worth tens of billions of pounds, and the Kingdom is the only substantial rival to Iran among the Muslim states of the Middle East. It also has the second-largest oil reserves in the world, with a shade under 300 billion barrels, and its sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund, is one of the biggest globally, with assets of more than half a trillion dollars.

From a brutally cynical realpolitik point of view, Edelman’s decision is a no-brainer. Mohammed bin Salman has almost limitless money to spend and a desire to spread it around for his country’s benefit; and, as the argument always goes, someone will work with them so it may as well be Edelman. In the uncertain post-pandemic world, a lucrative relationship with a high-spending client is manna from heaven.

Engagement is also a persuasive argument: the international community will naturally prefer jaw-jaw to war-war, and Edelman can argue that by working with the Saudis it is more likely that the Kingdom will liberalise and return to observing international norms, whereas isolation would leave them free to do as they pleased with little comeback.

But it’s a delicate balance. Especially in an era when so many businesses made the decision to take a financial hit and pull out of Russia, so egregious were their actions in Ukraine. Where that threshold sits for disengagement is not an easy one. Western politicians and business leaders will be willing to accept that money has no smell—no matter how much of it there is—but will want to see tangible benefits beyond simple financial profit. For Edelman, veterans of the game, there will need to be internal KPIs in their planning – tangible signs of liberalisations, or at least moderation – to use as ethical chips in the ongoing financial and geopolitical game.

There is much talk of “ethical investment” in the current economy. Partnering a repressive regime funded by petrochemicals is a high-risk enterprise. Behind closed doors, most policy-makers would probably agree it is the sensible thing to do, but Edelman must have a care for their own reputation as well as their client’s. Failure is not an option.