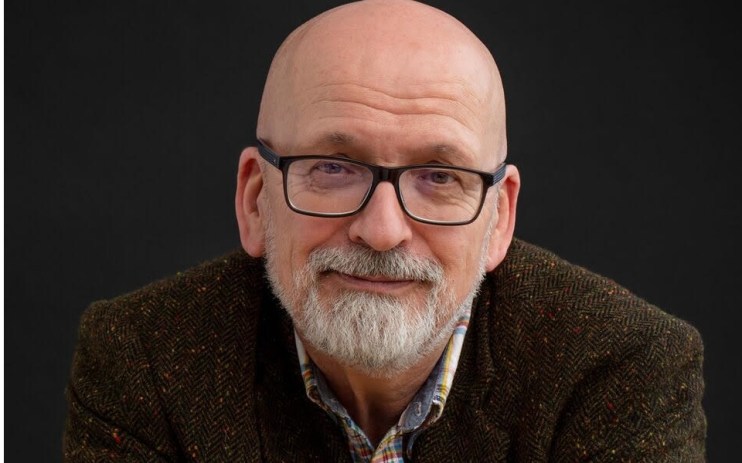

Roddy Doyle: The beloved author opens up on growing older, Irish politics and why he’s still angry

Roddy Doyle is one of the most well known and beloved contemporary Irish authors. His work includes the Two Pints series and The Commitments, as well as numerous children’s books. We caught up with him on the eve of a new speaking tour.

Hi Roddy. Your speaking tour, Conversations with Roddy Doyle, begins soon. Why are you doing it now?

Well I’ll be reading a lot of my old novels, and I think I’ve reached a stage in my life where I’m comfortable looking back on work I’ve done, rather than just what I’m currently doing. After I wrote The Commitments I didn’t read it or watch the film for 20 years, right up until I agreed to adapt it for a musical.

That felt both familiar and unfamiliar, but I was rather impressed by it, and felt comfortable claiming it as my own, even though it was written by a much younger man. I really enjoyed writing that adaptation, making little changes to the text, going to the opening night, and seeing the audience enjoy it too. It was a joyful experience for me, whereas in the past if people spoke about work I’d done twenty years ago I’d almost resent it, because they weren’t talking about the work I’m doing now.

Does that comfort come with age? For some writers, reading old work can be torturous.

I suppose I feel confident in the quality of the writing I’m doing now. I think my last novel, Smile, is one of the best I’ve done, and I think Two Pints (a play Doyle wrote in 2017) was one of the better things I’ve done. I’ve got plenty of ideas to keep me going; I hope it’s not arrogance, but I feel confident that I’m not dining out on past work. I’ve also always enjoyed the social side – this is a solitary occupation, you know, and the house is usually empty except for a couple of dogs and the kettle.

Your new novel, Love, comes out in May. Is it a departure from your other work?

Not really! Love is about two men, the same age as myself, who used to be very close but now only meet very occasionally. They used to go on the tear together in Dublin but don’t anymore. So they meet to catch up and go to pub after pub – pubs feature a lot in the book – relearning the geography of their younger years.

Love is obviously partly about Dublin, which has been a dominant theme in your work. Have you seen it change a lot over the past twenty years? I ask because Rosie (a film Doyle wrote in 2018) strikes me as angrier than your earlier work set in the city.

Change is inevitable, and I wouldn’t want to live in a museum. But the change in Dublin has been both for the better and the worse. The area I grew up in has changed dramatically, gotten dramatically less affordable. I see Rosie as a sort of companion piece to The Woman Who Walked Into Doors, which I started writing in the early nineties. And it struck me, writing Rosie, that not much has changed in the living standards of working class women – if anything they’ve gotten worse, more drastic.

So there’s certainly an anger in Rosie, and in all my work. There’s a song by John Lydon’s band PiL called Rise which features the line ‘anger is an energy’. I remember hearing that line for the first time, and it making complete sense to me. I’m normally quite soft spoken and affable, and I was able to teach for 14 years without terrifying my students, but there’s a definite anger in me, and if I didn’t have that – even in my comedies – I wouldn’t be able to write. It’s a key part of the weaponry.

Young people in Ireland also seem angry. Were you heartened by Sinn Fein’s performance in the recent election?

It was very interesting and remains so. I’ll be intrigued to see what sort of a government emerges from the horsetrading that’s currently going on. I think politics in Ireland is very different to Britain – you’ve only had the one referendum in the past few years, and it seems to me that its outcome was largely dictated by older people. In Ireland, the last two significant referendums, same sex marriage and abortion, were dominated by younger voters, and that energy seemed to continue into the general election.

Our politics have been dominated by two very similar parties (Fianna Fail and Fine Gael) since the foundation of the state – ok, maybe there are some differences in their support, but when you put them both in the stew there’s not much to distinguish the carrots and the parsnips. Finally young people have broken that. They voted left, they voted for a change, and I think that is very encouraging, because the only way we’ll sort out the housing and the health crisis is if young and working class people grab the country by the scruff of the neck and say enough is enough.

You’ve written a number of children’s books, like the Giggler Treatment, which I grew up reading. Did you decide to write for children because you had kids of your own?

I certainly wrote The Giggler Treatment for my own children. They were young at the time, and they’re all grown up now. They don’t read all my work, but they’ve read some. If there’s an occasion I like them to be involved – say I’ve got a play opening, I like them to come to opening night, but I’ve tried not to inflict my work on them. And luckily they don’t get much attention with a surname like Doyle in Ireland.

Do you think Irish literature is in a good place?

I think it’s better than it has been for ages. Sally Rooney is brilliant, obviously, the clarity of her writing is wonderful. It’s a bit frightening really, because she’s the same age as my oldest child. There’s another young woman Caoilinn Hughes who has a wonderful, mad book called The Wild Laughter that I would recommend wholeheartedly. There’s so much out there that I could read nothing except Irish writers and not get bored.

You’re obviously part of an older cohort of Irish writers. Do you ever miss being young?

Only when I’m running for buses. I truly don’t miss much about being young, although mortality raises its ugly head more and more nowadays. It used to be parents, aunts and uncles dying, then cousins start dying, best friends start dying. So you’re kind of living under a cloud of grief all the time. I wouldn’t mind getting out from under that every now and then. But I’m content being who I am, and where I am. Although, I would say that part of the writing process is not being content – I am content, but I’m also not, and it’s the discontented part that creates the work.

• Roddy Doyle will be speaking at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, Southbank Centre on 11 March. For tickets go to southbankcentre.co.uk or for more information on Doyle. For more dates and tickets go to ticketmaster.co.uk